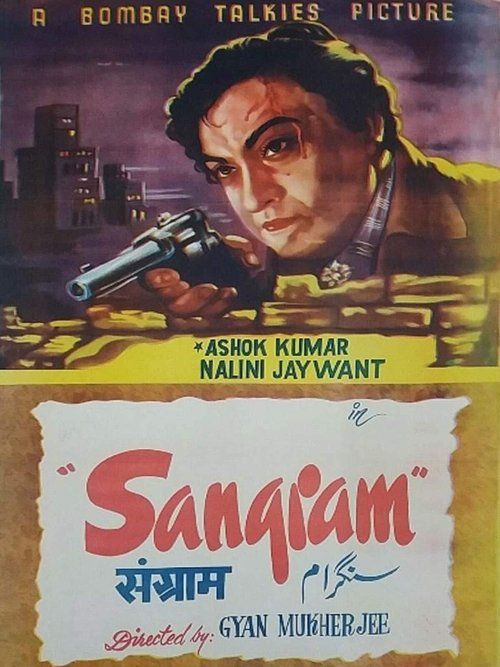

Sangram

"A father's duty, a son's destiny - the ultimate test of love and law"

Plot

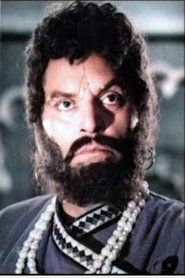

Sangram tells the poignant story of Inspector Dhanraj, a dedicated police officer whose life unravels after the tragic death of his beloved wife. Overwhelmed by grief and consumed by his demanding job, Dhanraj fails to provide proper guidance and discipline to his only son Ramesh, allowing him to grow into a spoiled and wayward young man. As Ramesh enters adulthood, his reckless behavior and poor choices lead him down a path of crime and moral decay, creating a devastating conflict between father and son. The film explores the tragic irony of a law enforcement officer whose own child becomes a criminal, forcing Dhanraj to confront his parental failures while upholding his professional duties. The narrative culminates in a powerful confrontation where duty and family loyalty collide, ultimately delivering a profound message about the consequences of neglect and the redemptive power of love and responsibility.

About the Production

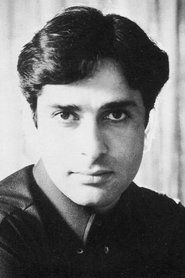

Sangram was one of the later productions from the legendary Bombay Talkies studio, which was facing financial difficulties during this period. The film was shot during a transitional phase in Indian cinema when the industry was moving from the studio system to independent productions. Director Gyan Mukherjee, known for his earlier classics like 'Kismet' (1943), brought his signature emotional storytelling style to this family drama. The production faced challenges securing adequate film stock due to post-war shortages, requiring careful planning of each scene. Young Shashi Kapoor, who would later become one of India's most celebrated actors, made one of his early screen appearances in this film.

Historical Background

Sangram was produced and released in 1950, a pivotal year in Indian history. The country was only three years into its independence after centuries of British colonial rule, and the nation was grappling with the challenges of nation-building, including the traumatic partition of India and Pakistan. The film industry itself was undergoing significant transformation, with the decline of the studio system (represented by Bombay Talkies) and the rise of independent producers. This period also saw the beginning of the 'Golden Age' of Indian cinema, which would produce some of the most iconic films in Indian cinematic history. The film's themes of moral duty, family responsibility, and the conflict between personal and professional obligations resonated strongly with audiences navigating the complexities of post-independence Indian society. The early 1950s also marked the beginning of India's industrialization efforts, and films like Sangram reflected the changing social dynamics and moral questions facing urban Indian families.

Why This Film Matters

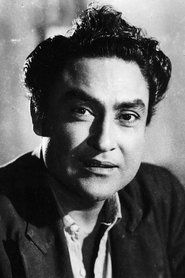

Sangram holds an important place in Indian cinema history as one of the early films to explore the psychological complexities of parent-child relationships in modern urban India. The film was part of a new wave of Indian cinema that moved away from mythological and historical subjects to tackle contemporary social issues. Its portrayal of a policeman's moral dilemma when confronting his own son's criminality was groundbreaking for its time and influenced numerous later films dealing with similar themes. The movie also represents an important milestone in the career of Ashok Kumar, who helped establish the naturalistic acting style that would become standard in Indian cinema. Additionally, it provides a valuable glimpse into the social values and family dynamics of urban India in the immediate post-independence period. The film's exploration of the consequences of parental neglect and the importance of moral education in child-rearing reflected the anxieties of a society undergoing rapid modernization and cultural change.

Making Of

The making of Sangram took place during a crucial transitional period in Indian cinema history. Bombay Talkies, once the premier film studio in India, was struggling with financial difficulties and internal conflicts during production. Director Gyan Mukherjee, who had previously delivered the massive blockbuster 'Kismet' with Ashok Kumar, was under pressure to create another successful film. The casting of young Shashi Kapoor was particularly notable, as he came from the illustrious Kapoor family of actors. According to contemporary accounts, Ashok Kumar took a personal interest in mentoring the young actor during filming. The production team faced several challenges including limited resources and the need to compete with the emerging independent production system that was revolutionizing Indian cinema. The film's emotional scenes between father and son reportedly required multiple takes, as both Ashok Kumar and young Shashi Kapoor had to convincingly portray their complex relationship dynamics.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Sangram was handled by the skilled cameramen at Bombay Talkies, known for their technical expertise and artistic vision. The film employed the visual style typical of early 1950s Indian cinema, with careful composition and dramatic lighting to enhance the emotional impact of key scenes. The use of shadow and light was particularly effective in scenes depicting the moral conflict faced by the protagonist. The camera work was more restrained compared to earlier Indian films, reflecting the growing influence of realistic cinema. Interior scenes were shot with attention to detail, creating authentic representations of middle-class Indian homes of the era. The cinematography also captured the urban landscape of Bombay, providing a valuable visual record of the city in the early post-independence period.

Innovations

While Sangram did not introduce revolutionary technical innovations, it represented the refinement of existing film techniques that were becoming standard in Indian cinema. The film demonstrated improved sound recording quality compared to earlier Indian films, allowing for more natural dialogue delivery. The editing techniques employed were more sophisticated than those of previous decades, with smoother transitions between scenes and better pacing of the narrative. The makeup and costume design effectively reflected the social status and character development of the protagonists. The film also benefited from the improved film stock and processing techniques available in the post-war period, resulting in better image quality. These technical improvements, while not groundbreaking individually, combined to create a more polished and professional final product that met the growing expectations of Indian audiences.

Music

The music for Sangram was composed by the renowned C. Ramchandra, one of the most influential music directors of Indian cinema's golden era. The soundtrack featured several memorable songs that blended traditional Indian melodies with Western musical influences, a style for which Ramchandra was famous. The lyrics were penned by Rajendra Krishan, a prolific songwriter known for his poetic and meaningful compositions. The songs in Sangram served not just as entertainment but as narrative devices that advanced the story and revealed character emotions. While specific song titles are not widely documented today, contemporary accounts suggest that the music was well-received and contributed significantly to the film's emotional impact. The soundtrack represented the evolving musical tastes of post-independence India, incorporating both classical and modern elements.

Famous Quotes

A policeman's duty is to the law, but a father's duty is to his child - when they conflict, the heart bears the wound

We give our children everything except what they need most - our time and guidance

The greatest crime is not what we do wrong, but what we fail to do right

In raising a child, the sins of neglect are as damaging as the sins of commission

When a father must choose between his badge and his boy, no choice brings peace

Memorable Scenes

- The emotional confrontation scene where Inspector Dhanraj discovers his son's criminal activities and must choose between his duty as a police officer and his love as a father

- The flashback sequences showing the happy family life before the mother's death, establishing the contrast with the present troubled relationship

- The final courtroom scene where moral justice and family loyalty reach their ultimate test

- The childhood sequences featuring young Shashi Kapoor, showing early signs of the character's future troubles

- The scene where Dhanraj reflects on his failures as a parent while looking at old family photographs

Did You Know?

- This was one of the earliest films to feature Shashi Kapoor, who was only about 12 years old at the time of filming

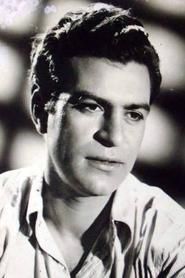

- Director Gyan Mukherjee was particularly known for his successful collaboration with Ashok Kumar, having previously directed the blockbuster 'Kismet'

- The film was produced by Bombay Talkies, one of India's most prestigious early film studios, during its final years of operation

- Nalini Jaywant was considered one of the most stylish actresses of her time and was known for her strong performances in dramatic roles

- The film's title 'Sangram' means 'struggle' or 'conflict' in Hindi, reflecting the central themes of the story

- Ashok Kumar, who plays the policeman father, was one of the first superstars of Indian cinema and known for his natural acting style

- The film was released during a significant period in Indian history, just three years after the country's independence

- The movie explored the relatively progressive theme of a police officer's moral dilemma when his own son becomes involved in criminal activities

- The film's music was composed by C. Ramchandra, one of the most influential music directors of that era

- This was one of the last major films directed by Gyan Mukherjee before his career declined in the 1950s

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Sangram for its powerful emotional narrative and strong performances, particularly Ashok Kumar's portrayal of the conflicted policeman father. The film was noted for its realistic approach to family drama and its willingness to tackle difficult moral questions. Critics of the time highlighted the natural acting style that was becoming increasingly popular in Indian cinema, moving away from the theatrical performances of earlier decades. The film's direction by Gyan Mukherjee was commended for its sensitive handling of the father-son relationship dynamics. Modern film historians and critics view Sangram as an important transitional film that bridged the gap between the studio era and the golden age of Indian cinema. While not as celebrated as some of its contemporaries, the film is recognized for its social relevance and its role in shaping the family drama genre in Indian cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Sangram received a positive response from audiences upon its release, particularly in urban centers where its themes of modern family life resonated strongly. The film's emotional core and the powerful performance by Ashok Kumar connected with viewers, many of whom were dealing with similar challenges of balancing traditional values with modern lifestyles. The father-son conflict struck a chord with audiences, and the film was particularly appreciated for its moral message about the importance of proper parenting and guidance. While it didn't achieve the blockbuster status of some other films of the era, it maintained steady box office performance and was remembered fondly by audiences of that generation. The film's reputation has grown over time among classic cinema enthusiasts, who appreciate its nuanced storytelling and its place in the evolution of Indian cinema's narrative style.

Awards & Recognition

- No major formal awards were recorded for this film, as the Filmfare Awards had not yet been established (they began in 1954)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Indian social films that dealt with family issues

- Hollywood family dramas of the 1940s

- The theatrical traditions of Indian storytelling

- The emerging realist cinema movement in India

- Post-war international cinema focusing on psychological themes

This Film Influenced

- Later Indian films exploring police-family conflicts

- 1970s and 1980s Bollywood films about father-son relationships

- Indian cinema's continued exploration of social issues through family narratives

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Like many Indian films from the 1950s, Sangram faces preservation challenges. The film exists in archives but may not have undergone complete digital restoration. Some prints are maintained in the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) and in private collections. The film's survival status is considered vulnerable, with potential degradation of existing prints. Efforts to preserve classic Indian cinema have increased in recent years, but many films from this era remain at risk. Digital copies may be available through specialized classic film distributors and archives, but high-quality restored versions are not widely accessible to the general public.