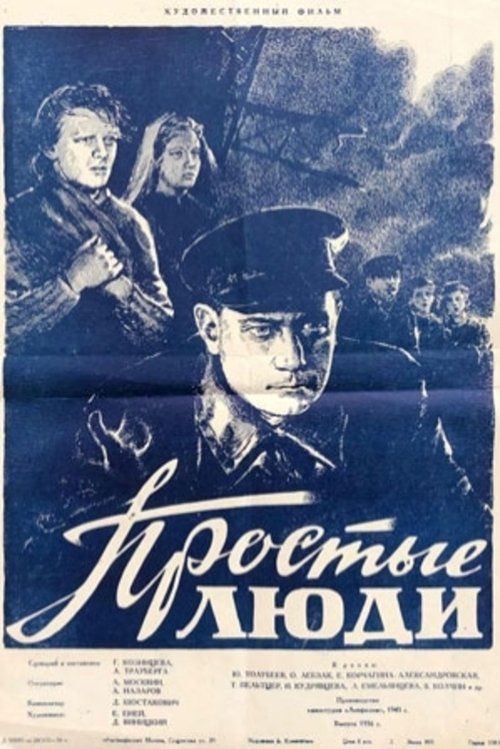

Simple People

Plot

Simple People tells the story of ordinary Soviet citizens during World War II, focusing on the lives of workers in a Leningrad factory who continue production despite the siege. The film follows several characters including a young woman named Tanya who works tirelessly in the factory while her fiancé fights at the front, an older factory worker who becomes a father figure to younger employees, and various other workers whose personal dramas unfold against the backdrop of war. As the siege intensifies, the characters face increasing hardships including food shortages, bombardments, and personal losses, yet they maintain their commitment to the war effort and their belief in Soviet ideals. The narrative interweaves personal stories with the collective struggle, showing how ordinary people demonstrate extraordinary courage and resilience. The film culminates in a powerful demonstration of human solidarity and the triumph of the common people over adversity, emphasizing the theme that heroism lies in everyday perseverance and dedication to the greater cause.

About the Production

The film was shot during the final months of World War II and completed in 1945, shortly before the war's end. Production faced numerous challenges including wartime resource constraints and the recent siege of Leningrad, which had just been lifted in 1944. Director Grigori Kozintsev collaborated with his regular partner Leonid Trauberg on the screenplay, though Trauberg was not credited as co-director on this film. The production utilized actual factory workers as extras and filmed in real industrial settings to achieve authenticity. The film's original cut was approximately 95 minutes, but the 1956 re-edited version was shortened to about 78 minutes.

Historical Background

Simple People was produced in 1945, at the end of World War II and the beginning of Stalin's post-war cultural crackdown. The Soviet Union, while victorious in the war, faced enormous devastation and was entering a period of renewed political repression under Stalin. The film emerged during the brief cultural thaw that occurred immediately after the war, when artists had slightly more freedom to explore complex themes and humanistic values. However, this window of opportunity closed quickly with the onset of the Cold War and Stalin's renewed emphasis on ideological conformity. The film's banning in 1946 was part of a broader campaign led by Andrei Zhdanov to enforce strict socialist realism in all arts, punishing any works deemed too individualistic, formalist, or insufficiently ideological. This period, known as the Zhdanov Doctrine, resulted in the persecution of numerous artists, writers, and composers. The film's eventual re-release in 1956 occurred during the Khrushchev Thaw, a period of de-Stalinization and cultural liberalization following Stalin's death in 1953. The transformation of the film's reception from banned subversive work to officially sanctioned art illustrates the dramatic shifts in Soviet cultural policy during this turbulent decade.

Why This Film Matters

Simple People represents a crucial but largely forgotten chapter in Soviet cinema history, embodying the struggle between artistic integrity and political conformity. The film's attempt to present a more nuanced and humanistic vision of Soviet life during wartime challenged the prevailing doctrine of socialist realism, which demanded idealized heroes and clear ideological messages. Its suppression became a symbol of artistic resistance and the dangers of political interference in creative expression. The film's fate mirrored the broader Soviet cultural landscape, where artistic innovation was often punished and conformity rewarded. In the context of world cinema, Simple People represents an alternative approach to war filmmaking that emphasized psychological depth and ordinary experience over heroic spectacle. The film's influence can be seen in later Soviet works that attempted to humanize the war experience, such as Mikhail Kalatozov's 'The Cranes Are Flying' (1957) and Andrei Tarkovsky's 'Ivan's Childhood' (1962). Today, Simple People serves as a reminder of the many works lost to political censorship and as evidence of the vibrant artistic community that existed beneath the surface of Soviet cultural control.

Making Of

The production of Simple People took place during a pivotal moment in Soviet history, as the country was transitioning from war to peace. Director Grigori Kozintsev, working at Lenfilm Studios, sought to create a more intimate and humanistic war film that focused on the psychological and emotional experiences of ordinary people rather than grand heroic narratives. The casting process was unusual for the time, with Kozintsev choosing relatively unknown actors to achieve greater authenticity. Olga Lebzak, a theater actress with minimal film experience, was cast in the lead role after an extensive search. The production team faced significant challenges filming in post-siege Leningrad, where many buildings were still damaged and resources were scarce. The cinematography, handled by Andrei Moskvin, employed innovative techniques including deep focus and natural lighting to create a more realistic and intimate visual style. The relationship between Kozintsev and co-screenwriter Leonid Trauberg became strained during production, with creative differences contributing to Trauberg's reduced role. The film's editing was particularly meticulous, with Kozintsev experimenting with montage techniques that would later be criticized as 'formalist' by Soviet authorities.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Andrei Moskvin was innovative for its time, employing techniques that would later be criticized as 'formalist' but are now recognized as artistically significant. Moskvin utilized deep focus photography to create complex visual compositions that allowed multiple layers of action within single frames. The lighting design emphasized naturalism, using available light sources to create authentic industrial and domestic atmospheres. The camera work included extended takes and fluid movements that contrasted with the more static style typical of Soviet socialist realism. Moskvin also experimented with low-angle shots and dramatic shadows to create psychological depth and emotional resonance. The visual poetry of the film was particularly evident in scenes depicting the factory environment, where machinery and human activity were choreographed into powerful visual metaphors. The black and white cinematography made effective use of tonal contrast to enhance the film's emotional impact and thematic concerns.

Innovations

Simple People featured several technical innovations that were ahead of their time in Soviet cinema. The film's use of location shooting in actual factories and working-class neighborhoods was unusual for the period, as most Soviet films of the 1940s were primarily studio-bound. The production team developed new techniques for filming in industrial environments, including specialized lighting setups that could handle the challenging conditions of factory spaces. The sound recording team created innovative methods to capture authentic industrial sounds while maintaining dialogue clarity. The film's editing experimented with rhythmic montage techniques that created visual and emotional parallels between different characters and situations. These technical achievements contributed to the film's distinctive visual style and immersive quality, though they also contributed to the accusations of formalism that led to its banning.

Music

The musical score was composed by Dmitri Kabalevsky, one of the Soviet Union's prominent composers who often worked in film. Kabalevsky's music for Simple People represented a departure from the bombastic, patriotic scores typical of Soviet war films, instead employing more subtle and intimate musical themes that reflected the film's focus on ordinary people. The soundtrack incorporated elements of Russian folk music adapted for orchestral arrangement, creating a sense of cultural authenticity while maintaining artistic sophistication. The music was used sparingly, with long stretches of natural sound and dialogue, reflecting the film's realist aesthetic. Kabalevsky's score was particularly effective in scenes of emotional crisis, where the music provided psychological insight without overwhelming the visual narrative. The sound design emphasized the industrial sounds of the factory, creating a rhythmic backdrop that connected the human drama to the larger context of wartime production.

Famous Quotes

In times of darkness, even the smallest light becomes a beacon of hope.

We are not heroes in the stories they tell, but we are heroes in the life we live.

The machines may make the weapons, but our hearts make the victory.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the factory at dawn, with workers arriving as steam rises from the machinery, creating a visual metaphor for industrial awakening and human resilience

- The scene where Tanya receives news from the front, filmed in a single continuous take that captures her emotional journey from hope to despair and back to determination

- The collective meal scene in the factory canteen, where workers share their meager rations while singing a folk song, demonstrating community solidarity despite hardship

Did You Know?

- The film was banned in 1946 by Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin's cultural commissar, who criticized it for 'formalism' and 'lack of ideological clarity'

- Along with Eisenstein's 'Ivan the Terrible, Part II', this film was a centerpiece of Zhdanov's anti-formalism campaign

- The film remained unseen by the public for eleven years until it was re-edited and released during the Khrushchev Thaw in 1956

- Director Grigori Kozintsev publicly disowned the 1956 re-release version, stating it was 'mutilated' and 'betrayed the original artistic vision'

- The original 1945 version is believed to be lost, with only the re-edited 1956 version surviving in film archives

- Olga Lebzak, who played the female lead, was a relatively unknown actress who disappeared from film after this movie

- The film was one of the first Soviet productions to attempt a more nuanced, humanistic portrayal of ordinary people during wartime

- Zhdanov's criticism specifically targeted the film's 'psychological individualism' and 'insufficient attention to collective heroism'

- The banning of this film marked the beginning of a period of intense cultural repression known as the Zhdanov Doctrine

- Despite being banned, the film was screened privately for film students and critics as an example of 'formalist deviation'

What Critics Said

Upon its completion in 1945, Simple People was praised by a small circle of Soviet critics who appreciated its artistic innovation and humanistic approach. These early reviews highlighted the film's psychological depth, visual poetry, and nuanced performances. However, following Andrei Zhdanov's denunciation in 1946, official criticism became uniformly negative, with reviewers attacking the film for 'formalism', 'bourgeois individualism', and 'insufficient ideological clarity'. Soviet newspapers published scathing reviews condemning the film's artistic choices as politically dangerous. After the 1956 re-release, critical reception was mixed, with some critics noting the film's artistic merits while others found the re-edited version confusing and compromised. International critics who have had access to the film through film festivals and archives have generally praised its visual style and humanistic vision, though many note that the re-editing appears to have damaged the original's artistic coherence. Contemporary film historians view Simple People as an important example of suppressed Soviet cinema and a testament to the artistic courage of its creators.

What Audiences Thought

Due to its banning in 1946, Simple People never reached a general Soviet audience in its original form. The 1956 re-release version had limited distribution and was overshadowed by more contemporary films. Audiences who did see the re-edited version reported confusion about the narrative structure, which had been compromised by the unauthorized reediting. Film students and cinephiles who have since discovered the film through special screenings and archives have generally responded positively to its artistic qualities and emotional depth. The film's reputation has grown over time among cinema enthusiasts, particularly those interested in suppressed works and the history of Soviet cinema. Today, Simple People is primarily known through film scholarship and retrospective screenings rather than popular audience reception.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet montage theory

- Italian neorealism

- French poetic realism

- Dziga Vertov's documentary style

- Eisenstein's psychological approaches

- Stanislavski's acting method

This Film Influenced

- The Cranes Are Flying (1957)

- Ballad of a Soldier (1959)

- Ivan's Childhood (1962)

- The Ascent (1976)

- Come and See (1985)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original 1945 version of Simple People is believed to be lost, likely destroyed during the period of its banning. The 1956 re-edited version survives in the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia and has been preserved through restoration efforts. Some fragments and outtakes from the original version may exist in private collections or film archives, but no complete print of Kozintsev's original cut has been discovered. The surviving version has been digitized and screened at various film festivals and retrospectives, allowing modern audiences to experience this historically significant work, albeit in its compromised form.