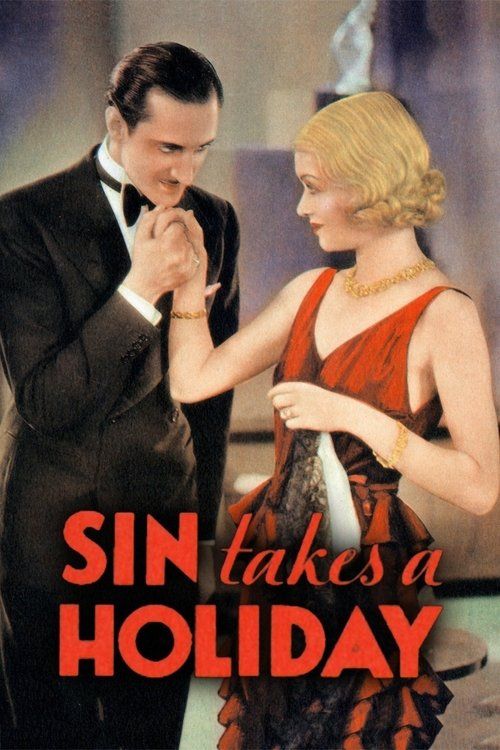

Sin Takes a Holiday

Plot

Dowdy secretary Sylvia Brenner accepts a marriage proposal from her wealthy boss Geoffrey Hammond, who only asks her to avoid an unwanted marriage to another woman. After their platonic arrangement, Sylvia uses Geoffrey's money to transform herself from an unattractive wallflower into a glamorous socialite, complete with fashionable clothes and sophisticated manners. During a luxurious trip to Paris, Sylvia meets the charming Reggie Williams and experiences her first true romantic awakening, leading her to contemplate an affair that would betray her marriage. As Sylvia navigates her newfound independence and attraction to Reggie, she must decide between the security of her convenient marriage and the passionate romance she's discovered. The film explores themes of female empowerment, sexual liberation, and the complexities of relationships during the permissive pre-Code era.

About the Production

Sin Takes a Holiday was produced during the transitional period from silent films to talkies, requiring the cast and crew to adapt to the technical challenges of early sound recording. The film was one of several collaborations between star Constance Bennett and director Paul L. Stein, showcasing Bennett's transformation from a silent film star to a successful sound actress. The costume department played a crucial role in depicting Sylvia's dramatic metamorphosis, creating an extensive wardrobe that reflected the character's journey from dowdy secretary to sophisticated socialite. The Paris sequences were filmed on elaborate studio backlot sets rather than on location, a common practice during this era due to budget constraints and the technical limitations of early sound equipment.

Historical Background

Sin Takes a Holiday was released in October 1930, during the early years of the Great Depression following the stock market crash of October 1929. This economic catastrophe created widespread unemployment and hardship, making escapist entertainment particularly valuable to American audiences seeking temporary relief from their financial worries. The film's themes of transformation and upward mobility would have resonated powerfully with viewers dreaming of better circumstances. The early 1930s also marked the final years of the pre-Code era in Hollywood, before the strict enforcement of the Hays Production Code in 1934, which would severely restrict the depiction of sexuality and adult themes in films. This period of relative creative freedom allowed filmmakers to explore more mature subject matter, as seen in Sin Takes a Holiday with its focus on a woman's sexual awakening and the possibility of infidelity. The film was also made during the technological revolution when Hollywood was fully transitioning from silent films to talkies, a transformation that was changing the very nature of cinema and requiring actors and filmmakers to adapt to new methods of performance and production.

Why This Film Matters

Sin Takes a Holiday represents an important example of pre-Code Hollywood cinema that was willing to explore adult themes and female sexuality with a frankness that would largely disappear from American screens after 1934. The film's focus on a woman's transformation and sexual liberation reflects the changing attitudes toward women's roles in society during the early 1930s, a period when women who had entered the workforce during World War I were redefining their social positions. Constance Bennett's portrayal of Sylvia Brenner contributed to the emerging archetype of the 'modern woman' in popular culture—independent, sophisticated, and unafraid to pursue her desires. The film also exemplifies the escapist fantasies that Hollywood offered to Depression-era audiences, with its tale of a humble secretary rising to wealth and glamour through marriage. While not as well-remembered as some other pre-Code films, Sin Takes a Holiday provides valuable insight into the social mores and cinematic conventions of its time, preserving a snapshot of American cultural attitudes just before the restrictive Production Code would reshape Hollywood's output for decades to come.

Making Of

Sin Takes a Holiday was produced during a pivotal time in Hollywood when the industry was fully transitioning to sound technology. Director Paul L. Stein, who had experience in both silent and sound films, had to navigate the technical challenges of early sound recording while maintaining visual storytelling. Constance Bennett, one of the most popular actresses of the era, was known for her sophisticated screen persona and fashion sense, making her perfect for the role of Sylvia's transformation. The film's costume department, led by Paramount's renowned costume designers, created an extensive wardrobe that visually documented Sylvia's metamorphosis from dowdy secretary to glamorous socialite. The Paris scenes, while filmed on studio backlots, required elaborate set designs to evoke the romantic atmosphere of the French capital. The film's exploration of a woman's sexual awakening was somewhat daring for its time, reflecting the more permissive pre-Code era before the enforcement of the Hays Code in 1934. Bennett's performance required her to portray both the insecure Sylvia and the confident woman she becomes, showcasing the range that made her one of the era's most bankable stars.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Sin Takes a Holiday reflects the transitional nature of early sound films, which were adapting visual techniques from the silent era while accommodating the technical requirements of sound recording. Early sound cameras were bulky and immobile, limiting the camera movement that had become common in late silent films. The cinematographer likely employed soft focus lighting to enhance Constance Bennett's beauty during her transformation scenes, a common technique in glamour photography of the era. The Paris sequences would have required atmospheric lighting to evoke the romantic ambiance of the city, possibly using backlit silhouettes and diffused lighting to create a dreamlike quality. The cinematography had to clearly capture the performances in dialogue scenes, as early sound recording required actors to remain relatively close to microphones hidden on set. The visual style would have emphasized the contrast between Sylvia's dowdy appearance and her glamorous transformation, using lighting and composition to highlight this character development throughout the film.

Innovations

Sin Takes a Holiday was produced using the Western Electric sound-on-film system, which Paramount Pictures had adopted for its sound productions. The technical challenges of early sound recording included bulky microphones that had to be hidden in sets, limiting camera movement and requiring actors to remain relatively stationary during dialogue scenes. The film's production team had to balance these technical constraints with the visual storytelling techniques developed during the silent era. The costume and makeup departments faced particular challenges in creating Sylvia's transformation, ensuring that the changes appeared believable on camera while accommodating the unforgiving nature of early sound film lighting. The film's Paris settings, created on studio backlots, required sophisticated set design and matte painting techniques to evoke the atmosphere of the French capital without the expense of location shooting. The film represents the technical sophistication Paramount had achieved in early sound production by 1930, with clear dialogue reproduction and a well-integrated musical score that enhanced rather than detracted from the storytelling.

Music

As an early sound film, Sin Takes a Holiday featured a musical score that combined original compositions with popular songs of the era. The soundtrack was performed by the Paramount studio orchestra, conducted by staff composers who created mood-appropriate music for the dramatic scenes. The score provided musical underscoring for key moments, particularly during Sylvia's transformation and her romantic encounters in Paris. The film likely included a theme song associated with Constance Bennett's character, a common practice in early musicals and dramas of the period. The sound design was relatively simple by modern standards, focusing primarily on clear dialogue reproduction and atmospheric music rather than sophisticated sound effects. The transition from silent to sound cinema meant that filmmakers were still learning how to effectively integrate music and sound into their storytelling, often resulting in a somewhat theatrical approach to audio elements. The soundtrack would have helped establish the sophisticated, cosmopolitan atmosphere of the film, particularly during the Paris sequences where French-inspired music might have been used to enhance the setting.

Famous Quotes

I married you to save myself from another marriage, not to give you a holiday from sin.

Paris has a way of making one forget the promises made in New York.

You've transformed my secretary into a woman I barely recognize.

Is it so wrong to want to be wanted for myself, not for what I can do for you?

In Paris, even respectable women take a holiday from their virtues.

Memorable Scenes

- Sylvia's transformation scene where she sheds her dowdy appearance for glamorous gowns and sophisticated hairstyles, marking her emergence as a confident socialite.

- The marriage proposal scene where Geoffrey asks Sylvia to marry him for convenience, establishing the premise of their platonic arrangement.

- The Parisian ballroom scene where Sylvia meets Reggie and feels the first stirrings of romantic attraction, set against an elegant backdrop of music and dancing.

- The confrontation scene where Geoffrey realizes his wife has transformed into an independent woman with desires of her own, challenging their original arrangement.

- The final decision scene where Sylvia must choose between her comfortable marriage and the passionate romance she's discovered in Paris.

Did You Know?

- This film was released during the pre-Code era, allowing it to explore adult themes of sexuality and infidelity that would soon be restricted by the Hays Production Code.

- Constance Bennett was one of the highest-paid actresses of the early 1930s, earning approximately $3,000 per week at the height of her career.

- Basil Rathbone, who plays the romantic lead Reggie, would later become famous for his portrayal of Sherlock Holmes in a series of films beginning in 1939.

- The film's provocative title was typical of pre-Code Hollywood's marketing strategy, using suggestive language to attract curious audiences.

- Director Paul L. Stein was an Austrian-born filmmaker who had directed films in both Europe and America before settling in Hollywood.

- The transformation sequence where Sylvia changes from dowdy to glamorous was a popular trope in 1930s cinema, reflecting society's fascination with makeovers and reinvention.

- The film was based on an original screenplay rather than a literary adaptation, which was somewhat unusual for the period.

- Early sound recording technology required actors to remain relatively stationary during dialogue scenes, limiting the camera movement that had been common in late silent films.

- The Paris setting, while filmed entirely on studio backlots, required elaborate set design and matte painting techniques to create the illusion of the French capital.

- This film was one of several pre-Code movies that explored female sexuality and empowerment themes that would largely disappear from American screens after 1934.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of Sin Takes a Holiday were generally positive, with critics praising Constance Bennett's performance and the film's sophisticated approach to adult themes. The New York Times noted Bennett's 'charming transformation' from dowdy secretary to glamorous socialite, while Variety highlighted the film's 'smart dialogue and polished production values.' Some critics found the plot somewhat formulaic but appreciated the film's stylish execution and the chemistry between Bennett and her co-stars. The Film Daily called it 'a thoroughly entertaining picture with plenty of romance and sophistication.' Modern reassessments of the film recognize it as a representative example of pre-Code cinema's willingness to explore female sexuality and empowerment, though it's often overshadowed by more famous films from the same era. Film historians have noted that while Sin Takes a Holiday may not be a masterpiece of the period, it offers valuable insights into the social attitudes and cinematic conventions of early 1930s Hollywood, particularly regarding women's roles and sexual agency.

What Audiences Thought

Sin Takes a Holiday appears to have been moderately successful with audiences in 1930, benefiting from Constance Bennett's growing popularity as one of Paramount Pictures' biggest stars. The film's themes of transformation and wish fulfillment likely resonated with Depression-era audiences seeking escapism from their economic hardships. While complete box office records from this period are difficult to verify, the film's release by a major studio and its star power suggest it reached a wide audience across the United States. The provocative title and adult themes would have attracted viewers curious about the more daring content being produced before the enforcement of the Hays Code. Audience reaction to Bennett's performance was particularly positive, helping solidify her status as one of the era's leading actresses and fashion icons. The film's focus on glamour and transformation, elements that Bennett was particularly known for, would have appealed especially to female viewers interested in the latest styles and the fantasy of social mobility through marriage.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The tradition of 'ugly duckling' transformation stories in literature and theater

- Contemporary plays and novels about marriage and sexuality

- The growing genre of sophisticated romantic comedies

- The 'woman's film' genre that was emerging in the early 1930s

- Pygmalion-style narratives about transformation through external intervention

This Film Influenced

- Later 'makeover' films featuring female protagonists

- Pre-Code films exploring female sexuality and empowerment

- Romantic comedies featuring marriage of convenience plots

- Films about social climbing and transformation in high society

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of Sin Takes a Holiday is unclear, as many films from this era have been lost or exist only in incomplete versions. If the film has survived, it would likely be preserved in the Paramount Pictures archive or at film preservation institutions like the Library of Congress or the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The survival rate for American films from 1930 is estimated to be around 70%, suggesting a reasonable possibility that Sin Takes a Holiday still exists in some form, though it may not have received modern restoration or be readily available for viewing.