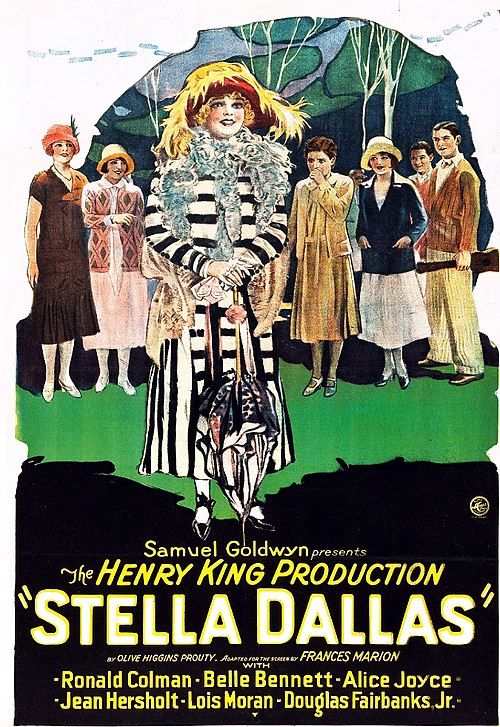

Stella Dallas

"The Story of a Woman Who Gave Up Everything for Her Daughter's Happiness"

Plot

Stella Martin, a vibrant and flamboyant working-class woman, marries Stephen Dallas, a wealthy man from a prominent Boston family. Despite her genuine love for Stephen and attempts to adopt refined manners, Stella's loud personality and poor taste constantly embarrass her husband and his social circle. As their daughter Laurel grows into a beautiful young woman, Stella realizes her presence and behavior are damaging Laurel's prospects in high society. In a profound act of maternal sacrifice, Stella distances herself from Laurel, allowing her daughter to secure her place in the upper-class world that Stella could never truly join, ultimately finding redemption through her selfless love.

About the Production

The film was one of Samuel Goldwyn's early prestige productions, shot during the transition period when Hollywood was establishing itself as the center of American cinema. The production faced challenges in adapting the complex novel for silent film, requiring careful visual storytelling to convey the nuanced social commentary and emotional depth of the source material.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the Roaring Twenties, a period of significant social change and economic prosperity in America. The 1920s saw increasing tensions between traditional values and modern sensibilities, with questions about class mobility, women's roles, and social conformity at the forefront of public discourse. The film's exploration of class differences reflected real social anxieties as America grappled with its identity as an increasingly industrialized and urbanized nation. The era also saw the rise of the 'New Woman' - more independent and assertive female figures - though Stella Dallas presented a more traditional view of womanhood centered on maternal sacrifice.

Why This Film Matters

Stella Dallas (1925) represents an important early example of Hollywood's engagement with social class issues in American society. The film helped establish the template for the 'maternal melodrama' genre that would become popular throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Its portrayal of a working-class woman's struggle for acceptance in high society resonated with audiences experiencing similar social tensions in their own lives. The film also contributed to the development of the 'woman's picture' genre, which focused on female-centered narratives and emotions. While largely forgotten today due to the fame of the 1937 remake, the 1925 version was significant in establishing Stella Dallas as an enduring American literary and cinematic character.

Making Of

Director Henry King worked closely with screenwriter Frances Marion to adapt the complex novel for the silent screen, focusing on visual storytelling techniques to convey the emotional depth and social commentary of the source material. Belle Bennett underwent extensive preparation for her role, studying the mannerisms and speech patterns of both working-class and upper-class women of the era. The production design was particularly crucial, with elaborate sets created to contrast Stella's humble origins with the opulent world of the Dallas family. The film was shot during a transitional period in Hollywood when studios were beginning to establish more sophisticated production methods, though still working within the technical limitations of silent cinema.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Ray Rennahan utilized the visual language of silent film to convey social contrasts and emotional states. The film employed sophisticated lighting techniques to distinguish between the warm, intimate world of Stella's origins and the cool, formal atmosphere of upper-class society. Camera work emphasized facial expressions and gestures, crucial for conveying emotion in the absence of dialogue. The visual style incorporated the soft focus and romantic lighting typical of mid-1920s melodramas, while also using composition and framing to highlight the social divisions central to the story.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film demonstrated sophisticated use of silent film techniques for emotional storytelling. The production utilized advanced lighting equipment to create visual contrasts between different social environments. The film also employed effective use of location shooting and studio sets to establish the social divisions central to the narrative. The intertitles, written by Frances Marion, were particularly well-crafted, providing necessary exposition while maintaining the emotional flow of the story.

Music

As a silent film, Stella Dallas was accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The original score was composed by Louis F. Gottschalk, Samuel Goldwyn's musical director, who created themes that emphasized the emotional journey of the characters. Theater orchestras would receive cue sheets with musical suggestions for different scenes, ranging from lively popular songs for Stella's early scenes to more classical and somber pieces for moments of sacrifice and loss. The music was crucial in establishing mood and enhancing the emotional impact of key scenes.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles. Key intertitles included: 'She who had nothing, gave everything', and 'A mother's love knows no social bounds'

Memorable Scenes

- The emotional climax where Stella watches from a distance as her daughter Laurel enters high society, realizing her sacrifice has allowed Laurel to succeed where she could not

- Stella's attempts to fit into upper-class society at a formal dinner party, ending in embarrassment

- The tender mother-daughter moments between Stella and young Laurel before the social divisions become apparent

- Stella's decision to leave her daughter's life for the girl's own good

Did You Know?

- This was the first film adaptation of Olive Higgins Prouty's 1923 novel, which was considered controversial for its frank depiction of class differences in America

- Belle Bennett's performance as Stella was critically acclaimed at the time but has been largely overshadowed by Barbara Stanwyck's performance in the 1937 remake

- Ronald Colman was already a major matinee idol when he was cast as Stephen Dallas, bringing significant star power to the production

- The film's intertitles were written by Frances Marion, one of the most prominent and respected screenwriters of the silent era

- The movie was categorized as a 'woman's picture' and was particularly popular with female audiences who related to Stella's maternal struggles

- Samuel Goldwyn considered this film one of his prestige productions, investing heavily in sets and costumes to accurately depict the contrast between working-class and upper-class lifestyles

- The film's theme of maternal sacrifice resonated strongly with 1920s audiences, reflecting the era's complex attitudes toward motherhood and social mobility

- This was one of the early films to directly address class consciousness in American society, a relatively bold topic for mainstream cinema of the time

- The success of this film helped establish Samuel Goldwyn as a major independent producer in Hollywood

- The original novel was inspired by Prouty's observations of social stratification in Boston society

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's emotional power and Belle Bennett's performance, with many reviews highlighting the film's ability to move audiences to tears. The New York Times particularly noted Bennett's 'powerful and convincing' portrayal of Stella's journey. Critics also appreciated the film's tasteful handling of sensitive social issues, avoiding melodramatic excess while maintaining emotional impact. Modern film historians recognize the 1925 version as an important adaptation that successfully captured the essence of Prouty's novel, though it's often evaluated in comparison to the more famous 1937 version.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success, particularly popular with female audiences who connected deeply with Stella's maternal struggles and sacrifices. Theater reports from the time indicated that many viewers were moved to tears by the film's emotional climax. The movie's themes of social aspiration and family dynamics resonated strongly with 1920s audiences, many of whom were experiencing their own journeys of social mobility in America's rapidly changing society. The film's success helped establish it as a property worthy of future adaptations, ultimately leading to the more famous 1937 version.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Olive Higgins Prouty's 1923 novel

- Contemporary social realist literature

- Victorian melodrama tradition

- American literary naturalism

This Film Influenced

- Stella Dallas (1937)

- Imitation of Life (1934)

- Mildred Pierce (1945)

- Other maternal melodramas of the 1930s-40s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives and has been preserved by film institutions, though complete pristine versions may be limited. Prints exist in the Library of Congress and other film archives. Some versions may be incomplete or show signs of deterioration typical of films from this era.