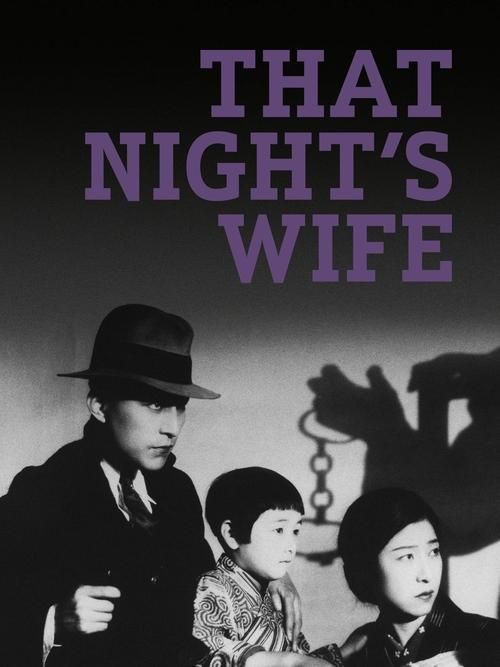

That Night's Wife

Plot

Shuji Hashizume, a struggling commercial artist, is driven to commit a daring bank robbery at gunpoint to secure funds for his critically ill daughter Michiko's medical treatment. After a tense escape through the city, Shuji takes a taxi home, unaware that the driver is actually Detective Kagawa in disguise. Upon arriving at his cramped apartment, Shuji reunites with his wife Mayumi, who informs him that the doctor believes Michiko will survive if she makes it through the night. When Kagawa reveals himself to arrest Shuji, Mayumi seizes the detective's gun and holds him at bay, demanding that her husband be allowed to stay by his daughter's side until dawn. The night becomes a claustrophobic psychological standoff as the three adults watch over the child, leading to an unexpected moral resolution when morning finally breaks.

About the Production

The film was Ozu's sixteenth production and was shot rapidly between late May and early July 1930. The head of Kamata Studio, Shiro Kido, personally recommended the source material to screenwriter Kogo Noda. Ozu famously toiled over the continuity of the film because six of the seven reels take place within a single, cramped apartment set. This technical challenge was so taxing that Kido reportedly urged Ozu to take a vacation at a hot spring after filming wrapped. The film is notable for being one of the few Ozu works to feature a significant amount of action and suspense, contrasting with his later, more static 'home dramas.'

Historical Background

Produced in 1930, the film captures Japan during the early years of the Great Depression and the 'Ero-Guro-Nansensu' (Erotic Grotesque Nonsense) cultural trend. This period was marked by a fascination with Western modernism, urban crime, and social instability before the rise of extreme militarism in the mid-1930s. The film reflects the 'shomin-geki' genre (drama about ordinary people) but infuses it with the 'keiko-eiga' (tendency film) spirit, which highlighted social inequalities and the struggles of the working class. The presence of Western posters and clothing illustrates the 'Mobo' (Modern Boy) culture of Tokyo, where traditional Japanese values were clashing with imported American lifestyle choices.

Why This Film Matters

That Night's Wife is a pivotal work in Ozu's filmography, serving as a bridge between his early genre experiments and his later refined style. It is celebrated by film historians as a prime example of 'Japanese Noir' before the term even existed, showcasing how Japanese directors adapted Hollywood tropes to local social realities. The film's focus on the domestic space as a site of moral conflict established the 'home drama' as a serious vehicle for psychological exploration. It also remains a significant document of the Shochiku Kamata 'Kamata Style,' which emphasized realism and the emotional lives of the urban middle class.

Making Of

The production was a 'labor of love' for Ozu, who was deeply immersed in American cinema at the time. He and screenwriter Kogo Noda condensed the original story—where the robbery occurred a week prior—into a single night to heighten the suspense and maintain a 'real-time' feel. Ozu experimented heavily with camera movement, including lateral tracking shots and sudden dollies, which he would later abandon for his signature static style. The set was designed to feel increasingly claustrophobic as the night progressed, using low-key lighting inspired by German Expressionism and early American crime films. Ozu's obsession with detail extended to the Western-style props and posters, which reflected his own 'cinephiliac' tendencies and the rapid Westernization of Tokyo.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Hideo Mohara (with assistance from Yuharu Atsuta) is characterized by its heavy use of shadows and 'noirish' low-key lighting. Unlike Ozu's later work, this film features active camera movement, including diagonal tracking shots that follow characters through the dark streets and around the apartment. The 'tatami shot' (low camera angle) is already present here, though it is used more for dramatic tension than the contemplative stillness of his later career. The film also makes effective use of close-ups on mundane objects—clocks, lamps, and water buckets—to build a sense of impending doom and the slow passage of time.

Innovations

The film is a masterclass in 'single-location' filmmaking, managing to sustain high tension within a one-room set for nearly an hour. Ozu's precise continuity editing was considered a major achievement at the time, ensuring that the spatial relationship between the three characters remained clear despite the cramped quarters. The integration of Western-style lighting techniques with Japanese domestic architecture was also seen as a sophisticated technical feat that elevated the film above standard 'pulp' adaptations.

Music

As a silent film, there was no original recorded soundtrack; however, it was designed to be accompanied by a live 'benshi' (narrator) and a small pit orchestra or solo pianist. Modern restorations, such as those by the Criterion Collection, often feature newly commissioned scores that emphasize the film's suspenseful and melancholic atmosphere. Ozu's visual cues for sound (like the ringing of a telephone or the ticking of a clock) provide a rhythmic structure that guides the musical accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

Intertitle: 'If she makes it through the night, the worst will be over.' (Context: The doctor's prognosis for the sick daughter, setting the stakes for the film.)

Intertitle: 'I'll turn myself in when the child is better.' (Context: Shuji's promise to his wife and the detective.)

Intertitle: 'A detective is a human being too.' (Context: Reflecting the moral softening of Detective Kagawa as he watches the family.)

Memorable Scenes

- The opening heist and chase: A high-energy sequence through the dark, rain-slicked streets of Tokyo that feels like a direct homage to Hollywood noir.

- The Gun Grab: Mayumi suddenly seizing the detective's pistol to protect her husband, a rare moment of female-driven action in Ozu's cinema.

- The Dawn Resolution: As the sun rises, the tension evaporates, and the characters share a quiet moment of mutual understanding before the inevitable arrest.

Did You Know?

- The film is based on the short story 'From Nine to Nine' by American author Oscar Schisgall, which was published in the Japanese magazine 'Shin Seinen' (New Young Men).

- An American movie poster for a film starring Walter Huston is prominently displayed in the apartment, serving as a 'moral conscience' symbol as Huston was known for playing upright characters.

- Ozu used a rare 'overlap transition' in the reverse-angle shots of the apartment door, a technique he generally disliked and seldom used again.

- The film features early appearances by Chishu Ryu, who would go on to become Ozu's most frequent collaborator and the face of his mature masterpieces.

- It is one of only three Ozu films that take place almost entirely at night, the others being 'Woman of Tokyo' (1933) and 'Tokyo Twilight' (1957).

- The original Japanese title 'Sono yo no tsuma' is more accurately translated as 'The Wife, On That Night.'

- Despite being a silent film, Ozu attempted to 'visualize sound' through rhythmic editing and specific object close-ups, a precursor to his later sound design theories.

- In 1952, the film was remade by Koro Ikeda; Ozu saw a preview and dryly noted in his diary that it was 'troublesome.'

- The film's protagonist is a commercial artist, reflecting the 'modern boy' (moga/mobo) culture prevalent in 1930s urban Japan.

What Critics Said

At the time of its release, the film was highly praised by studio head Shiro Kido and received positive notices for its technical proficiency and suspenseful atmosphere. Modern critics, such as David Bordwell and Donald Richie, view it as a masterpiece of Ozu's silent period, noting its sophisticated use of space and lighting. While some contemporary viewers find the plot contrivances (like the wife suddenly having a gun) a bit melodramatic, most agree that the emotional core and visual rhythm are exceptionally modern. It currently holds high regard among cinephiles for its 'noirish' aesthetic and its early display of Ozu's thematic obsession with family loyalty.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success for Shochiku, appealing to urban audiences who were drawn to its mixture of Hollywood-style crime thrills and relatable family drama. The 'sick child' trope was a powerful emotional hook for 1930s audiences living through economic hardship. Today, it is a favorite at silent film festivals, often screened with live 'benshi' narration or new musical scores, where it is appreciated for its surprisingly fast pace compared to Ozu's later works.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Josef von Sternberg's 'Underworld' (1927)

- German Expressionist Cinema

- American Gangster Films of the 1920s

- The 'New Youth' (Shin Seinen) literary movement

This Film Influenced

- Stray Dog (1949) by Akira Kurosawa

- Woman of Tokyo (1933) by Yasujiro Ozu

- Dragnet Girl (1933) by Yasujiro Ozu

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is well-preserved and has been digitally restored. It is part of the Shochiku archives and has been released as part of major Ozu retrospectives.