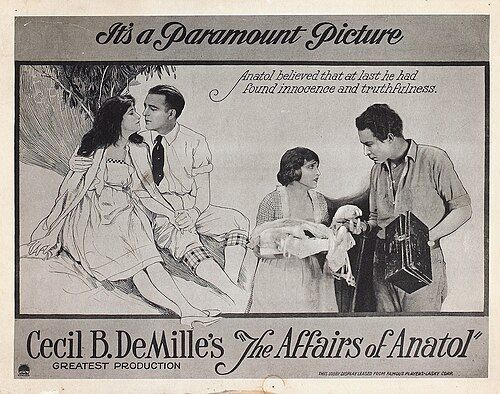

The Affairs of Anatol

"A Man's Search for Adventure in All the Wrong Places"

Plot

The Affairs of Anatol follows wealthy socialite Anatol Spencer, who grows bored with his seemingly perfect marriage to the virtuous Vivian. Convinced he needs to 'save' women from immoral situations, Anatol embarks on a series of misguided adventures, first attempting to rescue his former flame Emilie from a life of prostitution, only to discover she's content with her situation. He then tries to reform a suicidal artist named Satan Synne, becomes entangled with a faith healer's wife, and attempts to help a farm girl escape her abusive husband. Each episode reveals Anatol's hypocrisy and naivety as he projects his own desires onto these women, ultimately leading to his humiliation when he returns home to find his wife Vivian happily entertaining his best friend Max, forcing him to confront his own foolishness and the true nature of love and marriage.

About the Production

The film was shot in multiple episodes, each representing different 'affairs' or moral dilemmas. DeMille used the then-innovative technique of tinting different sequences in various colors to enhance emotional impact. The production featured elaborate sets including a lavish apartment, an artist's garret, and a rural farmhouse. Wallace Reid was recovering from a morphine addiction during filming, which affected his performance and contributed to his early death the following year.

Historical Background

Released in 1921, 'The Affairs of Anatol' emerged during a period of significant social change in America. The Jazz Age was beginning, and Victorian moral codes were being challenged across society. The film industry was transitioning from short films to feature-length productions, and Hollywood was establishing itself as the world's film capital. This period also saw the rise of the 'flapper' culture and changing attitudes toward sexuality and relationships. The film's exploration of marital dissatisfaction and the search for meaning beyond conventional morality resonated with audiences grappling with post-World War I disillusionment and the rapid social changes of the Roaring Twenties.

Why This Film Matters

The film represents an important early example of American cinema's engagement with European literary modernism and psychological complexity. Its episodic structure and moral ambiguity influenced later anthology films and character studies. The movie's frank treatment of sexuality and marital problems pushed boundaries for mainstream cinema and helped establish DeMille's reputation for combining spectacle with social commentary. Its success demonstrated that audiences were ready for more sophisticated, morally complex narratives, paving the way for the psychological dramas that would flourish in the late silent era. The film also contributed to the star personas of both Swanson and Reid, cementing their status as leading figures of early Hollywood.

Making Of

The production was marked by tension between DeMille and his leading man Wallace Reid, who was struggling with drug addiction during filming. Reid's condition worsened throughout production, requiring multiple takes and causing delays. DeMille, known for his perfectionism, clashed with Reid over his performance but ultimately worked around the actor's difficulties. Gloria Swanson, meanwhile, was at the height of her powers and demanded extensive costume changes and elaborate sets. The film's episodic structure allowed DeMille to experiment with different visual styles for each segment, creating a visually diverse work that showcased his technical prowess. The production design was overseen by Paul Iribe, who created lavish Art Deco sets that reflected the decadent lifestyle of the characters.

Visual Style

The film featured innovative cinematography by Karl Brown and Alvin Wyckoff, utilizing multiple camera techniques and lighting effects to create distinct visual moods for each episode. The production employed extensive use of soft focus lighting for romantic scenes and dramatic high-contrast lighting for moments of moral crisis. The cinematographers experimented with subjective camera angles to represent Anatol's psychological state, including distorted perspectives during his moments of confusion. The film's visual style was enhanced by elaborate intertitles with decorative Art Nouveau typography that reflected the sophisticated urban setting.

Innovations

The film pioneered the use of color tinting to enhance emotional storytelling, with different hues applied to entire sequences based on their emotional content. The production utilized the then-new Technicolor process for select scenes, though most of the film was black and white. DeMille employed complex lighting setups to create depth in his elaborate sets, using multiple light sources to achieve a three-dimensional quality. The film's editing techniques, particularly its use of cross-cutting between parallel storylines, were considered advanced for the time and influenced later narrative films.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Affairs of Anatol' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The original cue sheet suggested classical pieces including works by Chopin, Liszt, and Wagner to underscore the emotional moments. Paramount provided theaters with a detailed musical guide recommending specific compositions for each scene, with romantic themes for Anatol's encounters and dramatic music for moments of moral crisis. The musical accompaniment was designed to enhance the film's episodic structure, with distinct musical motifs for each of Anatol's 'affairs.'

Famous Quotes

Every woman needs to be saved, but not every woman wants to be saved.

Marriage is the tomb of love, but sometimes love needs to be buried to find peace.

In trying to save others, we often reveal our own need for salvation.

The greatest hypocrisy is believing oneself immune to the very weaknesses one condemns in others.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Anatol declares his boredom with married life to his wife Vivian in their lavishly decorated apartment

- The dramatic confrontation scene where Anatol discovers Emilie with another man, shattering his romantic illusions

- The artist's garret sequence where Anatol encounters Satan Synne, featuring expressionistic lighting and set design

- The final scene where Anatol returns home to find Vivian and Max together, forcing his moment of self-realization

Did You Know?

- Based on Austrian playwright Arthur Schnitzler's 1893 play 'Anatol', which was considered quite scandalous for its time

- The film was divided into seven distinct episodes, each showing Anatol's attempt to 'save' a different woman

- Cecil B. DeMille considered this one of his most personal films, exploring themes of morality and hypocrisy

- Wallace Reid died of morphine withdrawal complications just months after the film's release, making it one of his final performances

- The film featured early use of color tinting, with blue for night scenes, amber for interiors, and red for dramatic moments

- Gloria Swanson was paid $3,000 per week for her role, making her one of the highest-paid actresses in Hollywood at the time

- The original play had only six episodes, but DeMille added a seventh for the film adaptation

- The film's success led to DeMille and Swanson collaborating on several more films including 'Male and Female' and 'Forbidden Fruit'

- The movie's themes of infidelity and moral ambiguity were considered quite daring for 1921 audiences

- A young Agnes Ayres appeared in an uncredited role as one of the women Anatol attempts to 'save'

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's technical achievements and Swanson's performance, though some found the moral message confusing. The New York Times called it 'a fascinating study of human weakness' while Variety noted its 'unusual depth for a commercial picture.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film as an early example of DeMille's social critique, with some viewing it as a precursor to his later epics in its exploration of moral hypocrisy. The film is now recognized as an important transitional work between DeMille's early social dramas and his later spectacle films.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success, grossing over $800,000 domestically against its $175,000 budget. Audiences were drawn by the star power of Swanson and Reid and the film's scandalous themes. The movie's exploration of marital problems and infidelity resonated with urban audiences experiencing changing social mores. However, some conservative viewers found the film's moral ambiguity troubling, particularly its sympathetic portrayal of a 'fallen woman' in Emilie. Despite these controversies, the film's strong word-of-mouth and positive reviews helped it maintain a successful theatrical run throughout 1921 and into 1922.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Medal of Honor (1921) - Honorable Mention

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Arthur Schnitzler's play 'Anatol'

- European modernist literature

- Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theories

- German expressionist cinema

- Victorian melodrama

This Film Influenced

- The Cheat (1923)

- Forbidden Paradise (1924)

- The Merry Widow (1925)

- The Way of All Flesh (1927)

- The Divine Lady (1929)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress collection and has been restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive. A complete 35mm print exists and has been screened at various film festivals and retrospectives. The restoration work has preserved the original tints and some of the Technicolor sequences. The film is considered to be in good condition for a silent film of its era.