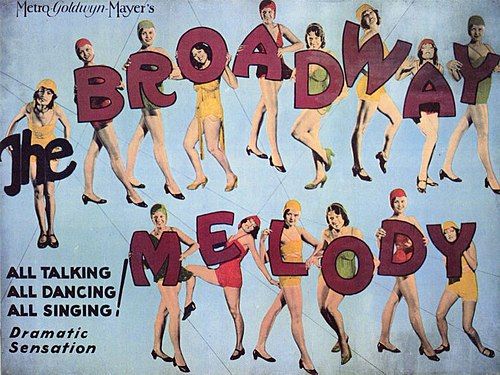

The Broadway Melody

"All Talking! All Singing! All Dancing!"

Plot

The Broadway Melody follows the Mahoney sisters, Harriet and Queenie, who bring their vaudeville act from the provinces to Broadway with dreams of stardom. Their childhood friend Eddie Kerns helps them secure a spot in Francis Zanfield's latest revue, but complications arise when Eddie falls for the beautiful Queenie. Simultaneously, Queenie catches the eye of wealthy socialite Jock Warriner, who showers her with expensive gifts and attention, creating a love triangle that threatens both the sisters' relationship and the show's success. Queenie initially gravitates toward Jock's glamorous lifestyle but gradually realizes he views her merely as a temporary diversion, while Eddie's love for her is genuine and lasting. The film culminates with Queenie choosing Eddie over Jock, but not before creating tension that nearly destroys her sister Harriet's career and their bond, ultimately resolving with a reaffirmation of sisterhood and true love.

About the Production

The Broadway Melody was originally conceived as a silent film but was converted to sound during production as the talkie revolution swept Hollywood. The production utilized multiple cameras to capture sound, a revolutionary technique at the time. The title sequence was filmed in early two-strip Technicolor, though the rest of the film is in black and white. MGM invested heavily in the film's sound technology, making it one of the most expensive productions of 1929. The musical numbers were pre-recorded and then lip-synced during filming, allowing for better audio quality than live recording could provide.

Historical Background

The Broadway Melody was produced during the tumultuous transition from silent films to talkies in Hollywood. The Jazz Singer (1927) had proven that sound pictures were commercially viable, and studios were scrambling to convert their productions. The stock market crash of 1929 occurred just months after the film's release, making its themes of ambition and success in the entertainment industry particularly resonant for audiences seeking escapism. The film reflected the Broadway boom of the 1920s, when musical theater was at its peak in American culture. It was also made during the early days of the Academy Awards, which were still establishing their prestige and criteria for excellence.

Why This Film Matters

The Broadway Melody revolutionized the film industry by proving that musicals could be commercially successful in the sound era. It established many conventions that would define the Hollywood musical for decades, including the backstage setting, love triangles, and the integration of musical numbers into the narrative. The film's success created a flood of musical productions throughout the 1930s, helping to save the film industry during the Great Depression by providing audiences with uplifting entertainment. It also demonstrated that films could successfully adapt Broadway sensibilities for the screen, creating a new hybrid art form. The film's portrayal of show business life influenced countless later works and helped cement Broadway as a symbol of American entertainment culture.

Making Of

The production of The Broadway Melody was fraught with the technical challenges of early sound recording. The studio had to deal with the limitations of microphones that could pick up every sound, including camera noises, which meant cameras had to be housed in soundproof booths. Director Harry Beaumont, who had primarily directed silent films, had to adapt his techniques to accommodate the new technology. The cast underwent extensive voice coaching to ensure their performances would record well. Anita Page and Bessie Love had to learn to sing for their roles, though some of their singing was dubbed. The film's choreography was simplified compared to stage shows because the bulky recording equipment restricted movement. MGM invested heavily in the film's marketing, promoting it as a technological marvel that would change cinema forever.

Visual Style

John Arnold's cinematography for The Broadway Melody was groundbreaking for its time, successfully adapting the visual language of silent film to the new requirements of sound recording. The camera work was necessarily static in many scenes due to the limitations of early sound equipment, but Arnold found creative ways to maintain visual interest within these constraints. The film used innovative lighting techniques to compensate for the lack of camera movement, creating dramatic shadows and highlights that enhanced the musical numbers. The Technicolor title sequence was particularly notable for its vibrant hues and smooth color transitions, demonstrating the potential of color in motion pictures. The dance sequences were choreographed specifically for the camera's fixed position, with performers arranged to create dynamic compositions within the frame.

Innovations

The Broadway Melody pioneered several technical innovations in early sound cinema. It was one of the first films to use pre-recorded musical numbers synchronized with on-screen performance, a technique that would become standard in musical films. The production utilized multiple camera setups to capture sound from different angles, allowing for more dynamic visual storytelling than earlier talkies. The film's sound mixing was particularly advanced for its time, successfully balancing dialogue, music, and sound effects. The Technicolor title sequence demonstrated the feasibility of combining color and sound, though the technology was still too expensive for use in an entire feature. The film also experimented with early forms of audio post-production, including sound effects and music editing techniques that would become fundamental to film sound design.

Music

The film's soundtrack consisted primarily of pre-existing songs rather than original compositions, including 'The Broadway Melody,' 'You Were Meant for Me,' 'Boy Friend,' and 'Truthful Parson Brown.' The music was supervised by Nacio Herb Brown and Arthur Freed, who would later become one of MGM's most successful musical producers. The songs were recorded before filming using the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system, then synchronized with the picture during post-production. This pre-recording allowed for better audio quality than live recording could provide, though it meant the actors had to lip-sync their performances. The soundtrack also included incidental music that helped bridge scenes and maintain the film's musical atmosphere. The musical numbers were staged in a relatively straightforward manner, focusing on performance rather than the elaborate choreography that would later become standard in MGM musicals.

Famous Quotes

Eddie: 'You were meant for me, and I was meant for you.'

Queenie: 'I'm tired of being poor. I want nice things.'

Harriet: 'We came here together, and we'll leave together.'

Eddie: 'Broadway's the only place for people like us.'

Jock: 'Money can buy anything, even happiness.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening number 'The Broadway Melody' where the sisters perform their vaudeville act for the first time in New York

- The romantic duet 'You Were Meant for Me' between Eddie and Queenie, one of the film's most tender moments

- The lavish party scene where Jock shows Queenie the glamorous lifestyle she could have

- The emotional confrontation between the sisters when Queenie chooses Jock over her family

- The finale where Queenie realizes her mistake and returns to Eddie, reconciling with her sister

Did You Know?

- The Broadway Melody was the first sound film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture at the 2nd Academy Awards

- It was the first all-talking musical produced by MGM

- The film's success spawned a series of unrelated films with similar titles: Broadway Melody of 1936, 1938, and 1940

- Bessie Love received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress, making her one of the first nominees in that category

- The film was originally titled 'The Melody of Broadway' but was changed before release

- Despite being a musical, the film contains no original songs - all were written for other shows

- The title sequence was filmed in Technicolor, making it one of the earliest color sequences in a sound film

- Charles King was the only member of the principal cast who had appeared on Broadway before the film

- The film was remade in 1936 as 'Broadway Melody of 1936' with Jack Benny and Eleanor Powell

- The film's success helped establish MGM as the leading studio for musical films during the early sound era

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised The Broadway Melody as a technological marvel and entertaining spectacle, with Variety calling it 'a fine piece of screen entertainment' and The New York Times noting its 'splendid musical numbers.' However, some critics found the plot formulaic and the acting uneven. Modern critics have a more mixed view, acknowledging the film's historical importance while noting its dated elements. The film is recognized for its technical achievements in early sound recording and its role in establishing the musical genre, though many agree it hasn't aged as well as other early musicals like 42nd Street or Top Hat. The film holds a 50% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with consensus focusing on its historical significance over its artistic merits.

What Audiences Thought

The Broadway Melody was a massive commercial success, becoming one of the highest-grossing films of 1929 and 1930. Audiences were thrilled by the novelty of an all-talking, all-singing, all-dancing picture, and the film played to packed houses across the country. The musical numbers, particularly 'The Broadway Melody' and 'You Were Meant for Me,' became popular hits that audiences requested to hear again. The film's success proved that there was a huge market for musical films, encouraging studios to invest heavily in the genre. Despite its popularity with general audiences, some theater owners complained about the high cost of installing sound equipment necessary to show the film, though the film's profitability eventually justified these investments.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award for Best Picture (1929/30)

- Academy Award for Best Writing (Adapted Screenplay) - Harry Beaumont (shared with others)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Broadway musical theater tradition

- The Jazz Singer (1927)

- Vaudeville performance style

- Early sound film experiments

- MGM's silent film productions

This Film Influenced

- Broadway Melody of 1936

- 42nd Street (1933)

- Gold Diggers of 1933

- Singin' in the Rain (1952)

- The Great Ziegfeld (1936)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Broadway Melody is preserved in the United States National Film Registry, selected for preservation in 2010 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. The film survives in its complete form, with both picture and sound elements intact. MGM (now owned by Warner Bros.) maintains the original negatives and preservation elements. The film has been restored multiple times, most recently for home video releases, with improved picture and sound quality. The Technicolor title sequence survives, though some color degradation has occurred over time. The film is considered well-preserved for its age, with no missing scenes or significant deterioration.