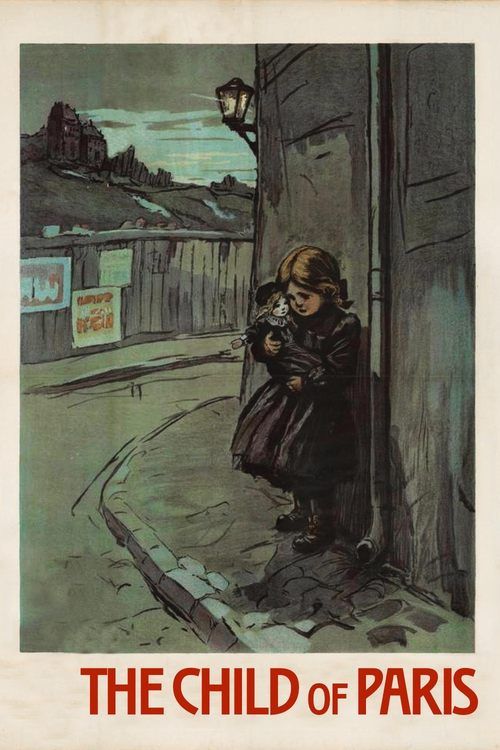

The Child of Paris

Plot

The Child of Paris follows the harrowing journey of a young girl, the daughter of an army captain who has gone missing in action. After running away from her boarding school in despair over her father's disappearance, she falls into the clutches of a ruthless gang of Parisian criminals who kidnap her for ransom. The kidnappers flee with the child to Nice, but their plan is threatened when a kind-hearted employee of one of the accomplices discovers the crime and sets off in determined pursuit. What follows is a dramatic chase across France as the compassionate pursuer races against time to rescue the innocent child from her captors, navigating through the criminal underworld while facing numerous obstacles and moral dilemmas along the way.

About the Production

The Child of Paris was produced during the golden age of French cinema and was one of the most ambitious productions of its time. The film featured extensive location shooting in both Paris and Nice, which was relatively rare for the period. Director Léonce Perret utilized innovative camera techniques including tracking shots and dynamic camera movement that were groundbreaking for 1913. The production employed hundreds of extras for the Paris street scenes and utilized real locations rather than studio sets to create a sense of authenticity. The kidnapping sequences were particularly challenging to film due to the need for complex choreography and the involvement of child actors in potentially dangerous situations.

Historical Background

The Child of Paris was produced during a pivotal period in cinema history, just before World War I would dramatically alter the European film landscape. 1913 represented the peak of French cinema's global dominance, with French films accounting for nearly 60% of the world market. The film emerged during the transition from short films to feature-length narratives, reflecting the growing sophistication of cinematic storytelling. Paris in 1913 was a cultural epicenter, experiencing the Belle Époque's final glorious year before the devastation of war. The film's themes of military service and missing soldiers resonated deeply with contemporary audiences, as tensions were building across Europe. The technical innovations displayed in the film reflected France's position at the forefront of cinematic technology and artistic development. This period also saw the rise of the film director as a creative author, with figures like Perret helping establish the artistic credibility of cinema as a medium.

Why This Film Matters

The Child of Paris holds significant importance in film history as one of the early examples of the feature-length narrative film that helped establish the language of cinema. The film's success demonstrated the commercial viability of longer, more complex stories and contributed to the transition away from short-form cinema. Perret's innovative use of location shooting and mobile camera techniques influenced subsequent filmmakers and helped establish visual storytelling conventions that would become standard in cinema. The film also represents an important milestone in French cinema's golden age, showcasing the technical and artistic sophistication that made French films dominant in the global market before World War I. Its themes of child endangerment and urban danger reflected growing social concerns about modern city life and helped establish the crime thriller as a viable genre. The film's international success helped pave the way for the global film industry we know today and demonstrated cinema's power to transcend cultural and linguistic barriers.

Making Of

The making of The Child of Paris was a testament to Léonce Perret's innovative approach to filmmaking and his role as a pioneer of early French cinema. Perret, who was already an established actor and director at Gaumont, pushed the boundaries of what was possible in 1913 by insisting on extensive location photography rather than relying on studio sets. This decision created numerous logistical challenges, including obtaining permits to film on Paris streets, managing crowds of curious onlookers, and dealing with unpredictable weather conditions. The kidnapping sequences required careful choreography and the use of special effects techniques that were cutting-edge for the period. Perret also implemented innovative lighting techniques to create dramatic shadows and atmosphere, particularly in the nighttime scenes. The production was known for its relatively large budget and the use of hundreds of extras, which was unusual for the time. Perret's dual role as both director and lead actor required him to balance his performance with his directorial responsibilities, often having to direct scenes between takes while still maintaining character continuity.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Child of Paris was groundbreaking for its time, featuring innovative techniques that were ahead of most contemporary productions. Perret and his cinematographers utilized extensive location photography throughout Paris and Nice, creating a sense of realism and authenticity that was rare in 1913. The film employed dynamic camera movements including tracking shots during chase sequences, which required the development of mobile camera rigs. The cinematography made effective use of natural lighting, particularly in the exterior scenes, while also employing sophisticated artificial lighting techniques for interior and night scenes. The visual composition showed careful attention to framing and depth, with Perret using foreground and background elements to create complex visual narratives. The film also featured innovative editing techniques, including cross-cutting between parallel actions to build suspense during the pursuit sequences. The cinematographic style helped establish visual conventions for crime and thriller films that would influence the genre for decades.

Innovations

The Child of Paris featured several technical innovations that were significant for cinema in 1913. The film's use of extensive location shooting required portable equipment and lighting setups that were advanced for the period. Perret employed early forms of camera movement, including tracking shots that followed characters through city streets, which was technically challenging before the development of sophisticated camera mounts. The production utilized innovative editing techniques, including rapid cutting during suspense sequences and cross-cutting between parallel storylines to build dramatic tension. The film also demonstrated advanced understanding of visual continuity and narrative pacing, helping establish conventions that would become standard in narrative cinema. The kidnapping sequences featured special effects and stunt coordination that were ambitious for the time. The production's use of real urban environments and large crowds of extras demonstrated new possibilities for cinematic scope and realism.

Music

As a silent film from 1913, The Child of Paris was originally accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibitions. The typical presentation would have featured a pianist or small orchestra performing appropriate music to accompany the action on screen. While no specific original score documentation survives, it was common for films of this era to be accompanied by compiled classical pieces or popular melodies that matched the mood of different scenes. The kidnapping and chase sequences would have been accompanied by dramatic, fast-paced music, while emotional moments would have featured more lyrical selections. Some larger theaters might have employed full orchestras for prestigious productions like this one. Modern screenings of restored versions of the film are typically accompanied by newly composed scores or carefully selected period-appropriate music that recreates the original viewing experience.

Did You Know?

- The film was also known by its French title 'L'Enfant de Paris' and was one of the most successful French films of 1913

- Director Léonce Perret not only directed but also starred in the film, playing one of the lead roles while managing the complex production

- The film was particularly notable for its extensive use of location shooting, which was uncommon in cinema of this era

- The child actress who played the lead role was discovered by Perret and this was her film debut, though her name has been lost to history

- The film's success led to several international remakes and adaptations in subsequent years

- At 66 minutes, it was considered an unusually long feature film for its time, when most films were much shorter

- The production utilized some of the first mobile camera rigs in French cinema to create dynamic chase sequences

- The film was distributed internationally and was particularly successful in the United States, where it helped establish French cinema's reputation

- Perret employed real Parisian criminals as extras to add authenticity to the kidnapping sequences

- The film's themes of child endangerment and redemption were considered quite bold and controversial for 1913

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised The Child of Paris for its ambitious scope, technical innovations, and emotional power. French film journals of the time hailed it as a masterpiece of cinematic storytelling, with particular admiration for Perret's directorial vision and the film's realistic portrayal of Parisian life. International critics, especially in the United States and Britain, were impressed by the film's technical sophistication and compared it favorably to the best productions of their own national cinemas. The trade press noted the film's commercial potential and predicted it would be a significant success. Modern film historians and critics recognize The Child of Paris as an important transitional work that demonstrates the evolution of cinematic language from primitive to sophisticated forms. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of early cinema as an example of how French directors were pushing the boundaries of the medium in the pre-war period.

What Audiences Thought

The Child of Paris was enormously popular with audiences upon its release in 1913, becoming one of the biggest box office successes of the year in France. French audiences were particularly drawn to the film's realistic depiction of familiar Parisian locations and its emotionally engaging story of a child in peril. The film's success extended beyond France, with enthusiastic reception in international markets including the United States, where it was praised for its sophisticated storytelling and technical polish. Contemporary audience reports indicate that viewers were especially moved by the child's plight and the film's suspenseful chase sequences. The film's popularity helped establish the feature-length narrative as the preferred format for cinema audiences, contributing to the decline of short film programs. The emotional impact of the story and the film's technical sophistication created word-of-mouth buzz that sustained its theatrical run for many months, which was unusual for the period.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier French crime films by Gaumont

- Contemporary literary crime novels

- Stage melodramas of the Belle Époque

- Social realist literature about urban poverty

- American chase films of the early 1910s

This Film Influenced

- Later French crime thrillers of the 1920s

- German Expressionist crime films

- American gangster films of the 1930s

- French poetic realist films of the 1930s

- Modern kidnapping thriller films