The Dying Swan

"A tragic tale of love, betrayal, and artistic obsession"

Plot

Gizella, a beautiful mute young woman, is heartbroken and emotionally shattered after being betrayed by her wealthy playboy lover Viktor, who abandons her for another woman. In her despair, she joins a ballet company where she discovers her natural talent for dance and finds a new form of expression through movement. During a mesmerizing performance of 'The Dying Swan,' Gizella captivates Glinsky, an eccentric painter obsessed with capturing death authentically in his art, who becomes fascinated by her ability to embody mortality so convincingly. Glinsky convinces Gizella to model for him, believing she can help him achieve his artistic vision of portraying death genuinely, leading to a complex relationship that blurs the lines between art, life, and death. The film culminates in a tragic exploration of artistic obsession, emotional trauma, and the pursuit of capturing the essence of mortality through art.

About the Production

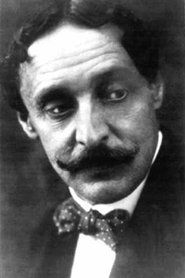

The Dying Swan was one of the last films directed by Yevgeni Bauer before his untimely death in 1917. The film was produced during the turbulent period of the Russian Revolution, which significantly impacted the Russian film industry. The ballet sequences were choreographed with great care, featuring authentic dance techniques of the period. The film was shot on location in Moscow studios, utilizing the sophisticated lighting techniques for which Bauer was renowned.

Historical Background

The Dying Swan was produced in 1917, one of the most tumultuous years in Russian history. The film was created between the February Revolution, which overthrew the Tsarist regime, and the October Revolution, which brought the Bolsheviks to power. This period of immense social and political upheaval dramatically affected all aspects of Russian life, including the film industry. The Russian cinema of this era, particularly works by directors like Bauer, represented a sophisticated artistic movement that was largely destroyed by the Revolution. Many filmmakers fled Russia, and the new Soviet government would eventually transform the film industry to serve ideological purposes. The film's themes of death, artistic obsession, and emotional trauma resonated deeply with audiences living through revolutionary violence and uncertainty.

Why This Film Matters

The Dying Swan represents a pinnacle of pre-revolutionary Russian cinema and showcases the sophisticated artistic achievements of the era. The film demonstrates early Russian cinema's focus on psychological depth and visual poetry, contrasting with the more narrative-driven approach of Western cinema. Bauer's innovative use of lighting, camera movement, and mise-en-scène influenced generations of filmmakers. The film's exploration of the relationship between art and death, and its complex portrayal of artistic obsession, anticipated many themes that would become central to European art cinema. The surviving fragments of the film provide crucial insight into the lost world of pre-revolutionary Russian culture and artistic achievement. Its rediscovery and restoration have been significant events in film preservation history.

Making Of

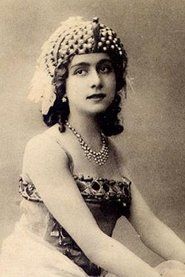

The Dying Swan was filmed during the chaotic period of early 1917, between the February and October Revolutions. Director Yevgeni Bauer, known for his sophisticated visual style and psychological depth, pushed the boundaries of cinematic expression in this film. The production faced numerous challenges due to the political instability, including shortages of film stock and resources. Vera Karalli's dual expertise as both a professional ballerina and actress brought authenticity to the ballet sequences. The film's elaborate sets and lighting design represented the pinnacle of Russian cinematic artistry before the Revolution disrupted the industry. Bauer's death shortly after completion meant he never saw the film's full impact on cinema history.

Visual Style

The Dying Swan showcases Yevgeni Bauer's masterful command of cinematic visual language. The film features sophisticated use of lighting to create emotional atmosphere and psychological depth. Bauer employed innovative camera techniques including tracking shots and unusual angles to enhance the narrative. The ballet sequences were filmed with particular care, using lighting and framing to emphasize the dancers' movements and emotional states. The film's visual style combines elements of Symbolism and Art Nouveau, creating a dreamlike, poetic atmosphere. The surviving footage demonstrates Bauer's sophisticated understanding of visual storytelling and his ability to convey complex emotions through cinematic means.

Innovations

The Dying Swan demonstrated several technical innovations for its time. Bauer's sophisticated use of mobile camera movements was particularly advanced for 1917. The film's lighting techniques, including the use of backlighting and shadow to create psychological effects, were ahead of their time. The ballet sequences required careful synchronization of camera movement with dance choreography, presenting significant technical challenges. The film's set design and art direction represented a high level of production sophistication. Bauer's editing techniques, particularly his use of cross-cutting to build psychological tension, were innovative for the period. The film's surviving footage demonstrates the technical sophistication achieved by Russian cinema before the Revolution.

Music

As a silent film, The Dying Swan would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score likely included classical pieces, particularly works by Russian composers such as Tchaikovsky, whose music was frequently used in ballet contexts. The ballet sequences would have featured appropriate dance music, possibly including Saint-Saëns' 'The Dying Swan' from Carnival of the Animals. Modern screenings typically feature newly composed scores or carefully selected classical music appropriate to the film's mood and period. The musical accompaniment would have been crucial to conveying the film's emotional narrative and enhancing the ballet sequences.

Famous Quotes

Art must be true to death to be true to life

In dance, I found my voice when words failed me

The swan does not die because it is weak, but because it is beautiful

Every artist must choose between life and art

Silence speaks louder than words when the heart is broken

Memorable Scenes

- The ballet sequence where Gizella performs 'The Dying Swan' with haunting emotional intensity

- The moment when Glinsky first sees Gizella dance and becomes obsessed with capturing her essence

- The heartbreaking scene where Gizella is betrayed by her lover Viktor

- The artistic confrontation between Gizella and Glinsky in his studio

- The final tragic scene that brings together themes of art, death, and redemption

Did You Know?

- Director Yevgeni Bauer died of pneumonia shortly after completing this film in June 1917, making it one of his final works.

- The film was considered lost for decades before being rediscovered and restored in the late 20th century.

- Vera Karalli, who plays Gizella, was a professional ballerina with the Bolshoi Ballet before becoming an actress.

- The ballet sequence 'The Dying Swan' was inspired by the famous choreography by Mikhail Fokine for Anna Pavlova.

- The film was produced by the Khanzhonkov Company, one of Russia's first and most important film studios.

- The Dying Swan is considered one of the masterpieces of early Russian cinema and Bauer's most psychologically complex work.

- The film's themes of artistic obsession and death were particularly relevant given the impending Russian Revolution.

- Only a partial version of the film survives today, with some scenes lost to time.

- The film's visual style influenced many later Russian filmmakers, including Sergei Eisenstein.

- The character of the painter Glinsky was reportedly based on real artists known to Bauer.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1917 praised The Dying Swan for its artistic ambition and psychological sophistication. Russian film journals of the era highlighted Bauer's masterful direction and Karalli's powerful performance. The film was particularly noted for its innovative visual style and emotional depth. Modern critics and film historians consider The Dying Swan one of the most important surviving examples of early Russian cinema. The film is frequently cited in scholarly works about pre-Soviet cinema and Bauer's contributions to film art. Contemporary film scholars have reevaluated the film as a masterpiece of psychological cinema, noting its sophisticated exploration of trauma, artistic obsession, and the relationship between life and art.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audiences in 1917 reportedly responded strongly to the film's emotional intensity and visual beauty. The ballet sequences were particularly popular with theater-goers familiar with Russian ballet traditions. The film's themes of betrayal and redemption resonated with audiences experiencing the social upheaval of the Revolution. Modern audiences viewing the restored version have been struck by the film's sophisticated psychological insights and visual artistry. The film has gained a cult following among silent film enthusiasts and cinema historians. Its limited availability has made screenings at film festivals and archival presentations significant events for classic cinema communities.

Awards & Recognition

- None documented from 1917 release period

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Symbolist literature

- Russian ballet tradition

- Psychological drama

- Art Nouveau aesthetics

- Fokine's choreography

- Russian Symbolist painting

This Film Influenced

- The Last Laugh (1924)

- The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

- Ballet Russes documentaries

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- Black Swan (2010)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Dying Swan is partially preserved with approximately 75% of the original footage surviving. The film was considered lost for decades before fragments were rediscovered in various archives. Restoration efforts have combined footage from Russian and international archives to create the most complete version possible. Some scenes remain lost, particularly from the film's conclusion. The surviving footage has been digitally restored and is preserved at the Gosfilmofond Russian State Archive. The film's partial survival makes it an important but incomplete document of pre-revolutionary Russian cinema.