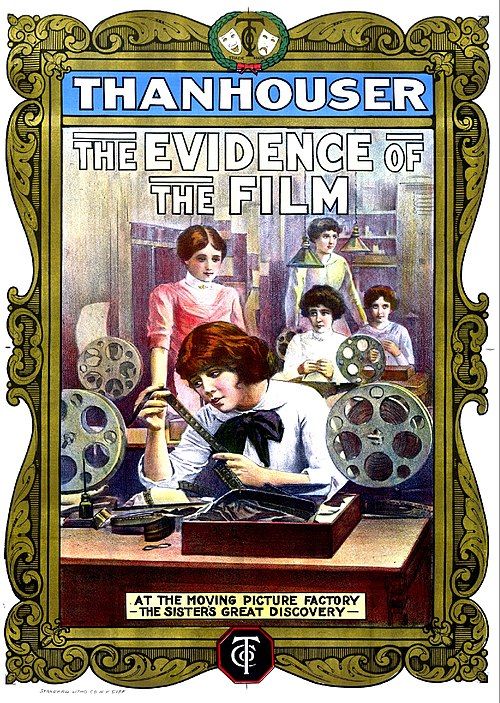

The Evidence of the Film

"A Thrilling Drama of the Moving Picture World"

Plot

A young messenger boy is falsely accused of stealing valuable bonds worth $20,000 while on his delivery route. The boy's accuser, a dishonest businessman, manages to convince the police of his guilt, leading to the messenger's arrest and imminent conviction. Coincidentally, a film crew is shooting a motion picture on the very same street where the alleged crime occurred, capturing the entire incident on camera. As the messenger boy faces trial, the film crew realizes their footage contains crucial evidence that proves his innocence. In a dramatic courtroom climax, the film is projected, revealing the true culprit and exonerating the wrongfully accused boy, demonstrating cinema's power to reveal truth and serve justice.

About the Production

This film was produced during the Thanhouser Company's peak period, when they were one of America's most respected film studios. The movie was shot on location in New Rochelle, where Thanhouser had established their studio facilities. The film's meta-narrative about filmmaking itself was relatively innovative for its time, reflecting the growing self-awareness of the film industry. The production utilized actual film equipment of the era, including hand-cranked cameras and natural lighting techniques typical of 1913 cinematography.

Historical Background

1913 was a pivotal year in American cinema, occurring during the transition from the short film era to feature-length productions. The film industry was rapidly consolidating, with the Motion Picture Patents Company (the 'Trust') dominating production and distribution. This period saw the rise of independent studios like Thanhouser that challenged the Trust's monopoly. The year also witnessed significant technological advancements, including improvements in camera stability and lighting techniques. Socially, 1913 America was experiencing rapid industrialization and urbanization, with growing concerns about crime and justice in modern cities. The Progressive Era was in full swing, with reforms targeting corruption and advocating for social justice. This film's emphasis on truth and justice resonated with contemporary audiences' concerns about fairness in an increasingly complex society. The film industry itself was gaining legitimacy as an art form and business, moving away from its reputation as cheap entertainment for the working class.

Why This Film Matters

'The Evidence of the Film' holds significant cultural importance as one of the earliest examples of meta-cinema, a film that reflects on the nature and power of filmmaking itself. Its narrative demonstrates the growing public awareness and acceptance of motion pictures as a legitimate medium capable of influencing society and revealing truth. The film's premise - that camera footage can serve as definitive evidence - was remarkably prescient, anticipating the crucial role that film and video would play in legal proceedings throughout the 20th century. As a Thanhouser production, it represents the studio's commitment to producing films with moral and educational value, not just entertainment. The movie also reflects the early film industry's self-consciousness about its cultural impact and potential for social good. Its survival and preservation make it an important document of early American cinema techniques and storytelling approaches. The film's themes of justice and truth-telling through technology continue to resonate in today's media-saturated world.

Making Of

The production of 'The Evidence of the Film' took place during the Thanhouser Company's golden age, when the studio was producing two one-reel films per week. Edwin Thanhouser, who had previously managed successful theaters, brought a theatrical sensibility to his film productions. The casting of Marie Eline, known as 'The Thanhouser Kid,' was significant as she was one of the studio's biggest box office draws. The film's meta-narrative approach was relatively innovative for 1913, reflecting the growing sophistication of film storytelling. The production likely utilized Thanhouser's state-of-the-art studio facilities in New Rochelle, which included glass-enclosed stages for optimal natural lighting. The film crew depicted in the movie was likely comprised of actual Thanhouser employees, adding authenticity to the production. The courtroom scenes were probably shot on constructed sets within the studio, following the common practice of the era.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Evidence of the Film' reflects the technical standards and practices of 1913 American filmmaking. The film was likely shot using hand-cranked cameras of the era, requiring careful operation to maintain consistent exposure and frame rates. Natural lighting was predominantly used, particularly for exterior scenes, taking advantage of sunlight filtered through the glass stages of Thanhouser's studio. The camera work is relatively static by modern standards, typical of the period, but includes some movement to follow the action. The film employs medium shots and long shots appropriate to the narrative, with closer shots used for emotional emphasis. The courtroom scenes likely used multiple camera positions to create visual interest within the confined space. The cinematography successfully captures the contrast between the gritty street scenes and the formal courtroom setting, enhancing the narrative's dramatic tension. The technical quality of the surviving print indicates competent professional work by Thanhouser's camera department.

Innovations

While 'The Evidence of the Film' does not represent major technical breakthroughs, it demonstrates the solid technical competence of the Thanhouser studio in 1913. The film's effective use of location shooting and studio sets shows the growing sophistication of American film production. The meta-narrative structure, while not technically innovative, represents an advanced approach to storytelling for its time. The film's preservation quality indicates good original processing and storage practices by Thanhouser. The movie's clear narrative structure and effective pacing demonstrate the studio's mastery of film editing techniques of the era. The use of film-within-a-film as a plot device required careful planning and execution, showing technical proficiency in coordinating multiple narrative layers. The film's successful integration of different filming environments - street scenes, studio sets, and the film crew's equipment - demonstrates the technical capabilities of early 1910s American cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Evidence of the Film' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have included a pianist or small ensemble performing appropriate music to enhance the dramatic moments of the film. The score likely included popular songs of the era as well as classical pieces adapted for silent film accompaniment. During tense moments, such as the accusation and trial scenes, the music would have been dramatic and suspenseful. The revelation of the film evidence would have been accompanied by triumphant or uplifting music. The exact original score is not documented, as was common for films of this period. Modern screenings of the film often feature newly composed scores or carefully selected period-appropriate music. The absence of recorded sound emphasizes the visual storytelling and acting, which were crucial elements of silent film performance.

Famous Quotes

['The camera never lies - it shows only the truth!', 'Justice will be served when the evidence is revealed.', 'In the darkness of the projector's beam, truth shall come to light.']

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic courtroom scene where the film footage is projected, revealing the true thief and exonerating the innocent messenger boy; The street scene where the film crew accidentally captures the crime; The moment when the film crew realizes their footage contains crucial evidence; The messenger boy's arrest and the community's reaction; The final scene of justice being served and the boy's vindication

Did You Know?

- This film is considered one of the earliest examples of cinema about cinema, featuring a meta-narrative about the filmmaking process itself

- The Thanhouser Film Corporation was one of the first film studios to establish a permanent facility in New Rochelle, New York, which became known as 'Hollywood on the East Coast'

- William Garwood, who plays a key role, was one of Thanhouser's most popular leading men and appeared in over 200 films during his career

- Marie Eline, known as 'The Thanhouser Kid,' was one of the first child stars in American cinema and appeared in numerous Thanhouser productions

- The film's title reflects the growing recognition of film as evidence in legal proceedings, a concept that would become increasingly important in the 20th century

- Edwin Thanhouser, the director, was a pioneer who sold his successful theater business to enter the fledgling film industry in 1909

- The film was released during a period when single-reel films (approximately 10-15 minutes) were the industry standard

- The $20,000 mentioned in the plot would be equivalent to over $500,000 in today's currency, emphasizing the gravity of the accusation

- The film's preservation and survival is remarkable, as an estimated 90% of American silent films have been lost

- This film was part of Thanhouser's strategy to produce films with moral and educational value, in addition to entertainment

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'The Evidence of the Film' was generally positive, with trade publications praising its clever premise and execution. The Moving Picture World, a leading industry journal of the era, commended the film for its originality and the effective use of cinema as a plot device. Modern critics and film historians recognize the movie as an important early example of meta-narrative in cinema. The film is often cited in scholarly works about early American cinema and the evolution of film language. Its inclusion in the National Film Registry (if applicable) or similar preservation efforts underscores its historical significance. Contemporary film scholars appreciate the movie's sophisticated understanding of cinema's potential to document reality and serve justice, themes that would become increasingly relevant throughout the 20th century. The film is frequently studied in courses on early cinema and film history as an example of Thanhouser's contribution to American film art.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1913 reportedly responded positively to 'The Evidence of the Film,' finding its premise both entertaining and thought-provoking. The film's clear moral message and satisfying resolution appealed to contemporary viewers' sensibilities. The presence of popular Thanhouser stars like Marie Eline likely contributed to its box office success. Modern audiences viewing the film through archival screenings and online platforms often express fascination with its early meta-cinematic approach and historical significance. The film's relatively short runtime and straightforward narrative make it accessible to contemporary viewers interested in silent cinema. Its preservation status allows modern audiences to experience an authentic example of early American filmmaking techniques and storytelling conventions. The movie continues to be featured in silent film festivals and retrospectives, where it is typically well-received by enthusiasts of classic cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Thanhouser productions with moral themes

- Contemporary crime dramas

- Stage plays about justice and innocence

- The growing body of American crime fiction

- D.W. Griffith's narrative techniques

This Film Influenced

- Later films about filmmaking

- Courtroom dramas using film evidence

- Meta-cinematic works

- Films about media and truth

- Early film noir elements

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives and has been preserved by film archives. A print exists in the collection of the Library of Congress and other film preservation institutions. The film has been made available through various archives and is considered one of the better-preserved Thanhouser productions. Its survival is particularly significant given the high loss rate of films from this period. The preserved print allows modern audiences to experience this important early American film in relatively good condition considering its age.