The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

"The Picture That Will Live Forever!"

Plot

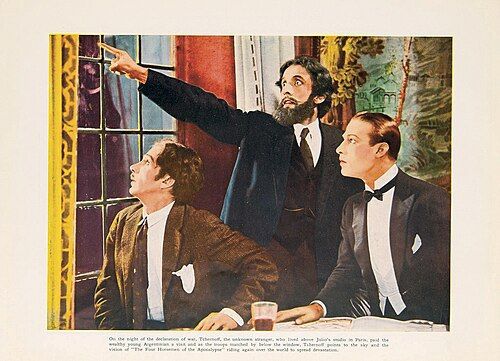

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse follows the wealthy Madariaga family, an Argentine ranching dynasty with French and German branches. After the patriarch's death, his two daughters marry men from their respective heritage countries - one French, one German - and relocate to Europe with their families. The story centers on Julio Desnoyers, the Argentine grandson who moves to Paris and becomes a notorious womanizer and artist, particularly famous for his passionate tango dancing. When World War I erupts, the family members find themselves fighting on opposing sides, with Julio eventually enlisting in the French army after a personal tragedy. The film chronicles the devastating impact of the war on both the family and civilization itself, culminating in Julio's heroic sacrifice on the battlefield as the four horsemen - War, Conquest, Famine, and Death - ride across Europe.

About the Production

The film was shot over 96 days with a budget that made it one of the most expensive films of its time. The famous tango scene was improvised by Valentino and his dance partner, and became so popular it sparked a tango craze across America. The battle sequences were filmed on a massive scale with thousands of extras and real artillery pieces. Director Rex Ingram insisted on authentic details, importing French military uniforms and equipment.

Historical Background

Made just three years after the end of World War I, the film captured the raw trauma and disillusionment that still gripped the world. The 1920s saw a wave of anti-war literature and cinema, but this adaptation of Vicente Blasco Ibáñez's 1916 novel was particularly resonant because it showed the war's impact on families and personal relationships. The film reflected America's emerging role as a global power and its complex relationship with European culture. It also came during the height of the Tango craze that had swept America from Argentina, making the film's timing perfect. The post-war period saw audiences hungry for both escapist entertainment and meaningful art that addressed their recent experiences.

Why This Film Matters

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse revolutionized American cinema in multiple ways. It established the epic war film as a serious genre and proved that audiences would respond to thoughtful, anti-war messaging. The film created the 'Latin Lover' archetype that would dominate Hollywood for decades, making Valentino the first true male sex symbol of cinema. Its massive commercial success demonstrated that foreign stories and settings could resonate with American audiences, paving the way for more international productions. The film's visual style influenced countless subsequent epics, particularly its use of light and shadow to convey emotional states. It also helped establish Metro Pictures as a major player, leading to the formation of MGM.

Making Of

The production was fraught with challenges from the beginning. Rex Ingram fought with studio executives over the film's length and budget, threatening to walk off the project multiple times. The casting of Valentino was controversial - many at Metro thought he was too exotic for American audiences. The tango sequence was nearly cut until Ingram insisted on keeping it after seeing test audiences' reactions. The massive battle sequences required coordination with the U.S. Army, who provided technical advisors and some equipment. Ingram's perfectionism extended to every detail - he had authentic French soil shipped to California for the trench scenes. The film's success led to Ingram being given complete creative control on future projects, rare for directors of the era.

Visual Style

The cinematography by John F. Seitz was revolutionary for its time. He pioneered the use of dramatic lighting to create emotional atmosphere, particularly in the tango scene where he used low-key lighting to create intimacy and danger. The battle sequences employed multiple cameras and innovative tracking shots to create a sense of chaos and realism. Seitz developed new techniques for filming night scenes using artificial lighting that looked natural. The film's visual palette evolved from the bright, warm colors of Argentina to the cold, dark tones of war-torn Europe. The famous final shot of the four horsemen riding across the sky used double exposure techniques that were groundbreaking for 1921.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would become standard in cinema. It was one of the first films to use the new panchromatic film stock, which allowed for more realistic skin tones and better low-light photography. The battle sequences employed a then-revolutionary system of multiple cameras filming simultaneously from different angles. The film's use of miniature models for long shots of destroyed landscapes was groundbreaking. Ingram developed new techniques for filming crowd scenes that gave them depth and movement. The famous tango sequence used innovative camera movements that followed the dancers, creating a sense of intimacy and energy. The film's editing, particularly in the battle scenes, used rapid cutting to create tension and chaos.

Music

As a silent film, it originally had no recorded soundtrack, but was accompanied by live orchestral music. The original score was composed by William Axt and David Mendoza, who created a full symphonic score that was published for theater orchestras. The score incorporated authentic tango music for the famous dance sequence, including 'La Cumparsita.' For the 1926 re-release with sound effects, Hugo Riesenfeld added synchronized sound effects using the Phonofilm process. Modern restorations have used various scores, including a 1998 version by Robert Israel that attempted to recreate the original orchestral feel. The music was crucial to the film's emotional impact, particularly during the battle sequences and the tragic finale.

Famous Quotes

The four horsemen will ride again... War, Pestilence, Famine, and Death.

In the beginning, there was the land... and the family... and the love that bound them together.

Tango is not just a dance... it is the expression of the soul in movement.

When the cannons speak, the hearts of men grow silent.

We are all brothers until the flags are unfurled.

Memorable Scenes

- The legendary tango sequence where Valentino, dressed in a gaucho costume, dances passionately with his partner, creating an atmosphere of raw sensuality and danger that made him an instant star.

- The massive battle sequences showing the horror of trench warfare, with thousands of soldiers charging across no man's land under artillery fire.

- The emotional family reunion scene where relatives from opposing sides meet before the war, foreshadowing their tragic division.

- The climatic final scene where the four horsemen are visualized riding across the war-torn landscape as Julio makes his heroic sacrifice.

- The opening scenes on the Argentine ranch, establishing the family's wealth and unity before the coming conflict.

Did You Know?

- The film was the sixth highest-grossing silent film of all time, adjusting for inflation

- Rudolph Valentino was not the first choice for the lead role; the studio wanted John Gilbert

- The tango scene single-handedly made Valentino a superstar and established the 'Latin Lover' archetype

- The film's success saved Metro Pictures from bankruptcy and led to the formation of MGM

- Author Vicente Blasco Ibáñez was so pleased with the adaptation that he gave Ingram a gold cigarette case

- The film was re-released in 1926 with added sound effects using the Phonofilm process

- Valentino's salary for this film was $1,250 per week, a huge sum for the time

- The battle scenes were so realistic that some audience members fainted during screenings

- The film was banned in several countries for its anti-war message

- Alice Terry and Rex Ingram fell in love during filming and married the following year

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics hailed the film as a masterpiece of cinema. The New York Times called it 'the most important picture yet produced' and praised Ingram's direction as 'poetic and powerful.' Variety noted that the film 'elevates the motion picture to the level of high art.' Modern critics continue to regard it as a landmark of silent cinema, with the American Film Institute ranking it among the greatest American films. The film's anti-war message is seen as ahead of its time, and its technical achievements, particularly the battle sequences, are still studied by film scholars. Critics particularly praise Ingram's use of symbolism and the film's emotional depth.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences responded to the film with unprecedented enthusiasm. It broke box office records across the country and ran for over a year in some theaters. Valentino became an overnight sensation, with women fainting in the aisles during his tango scene. The film sparked a national tango craze, with dance studios reporting record enrollment. Veterans of World War I particularly praised the film's realistic portrayal of combat, though some found it emotionally difficult to watch. The film's anti-war message resonated strongly with a war-weary public. Long lines formed outside theaters for weeks, and the film's success made it the cultural phenomenon of 1921.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Magazine Medal of Honor (1921)

- Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences - Special Award for Artistic Achievement (1929, retrospective)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

- Grand Illusion (1937)

- Gone with the Wind (1939)

- War and Peace (various adaptations)

- The Big Parade (1925)

- Wings (1927)

- What Price Glory? (1926)

This Film Influenced

- Ben-Hur (1925)

- The Ten Commandments (1923)

- The Birth of a Nation (1915)

- Intolerance (1916)

- The Big Parade (1925)

- Wings (1927)

- All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

- Gone with the Wind (1939)

- Doctor Zhivago (1965)

- War Horse (2011)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the National Film Registry and was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 1995 for being 'culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.' A complete 35mm print exists in the Library of Congress collection. The film underwent a major restoration in the 1990s by the Museum of Modern Art and the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The restored version premiered at the New York Film Festival in 1998. The film is also preserved in the MGM archives and several international film archives. While some footage remains lost or damaged, the majority of the film survives in good condition.