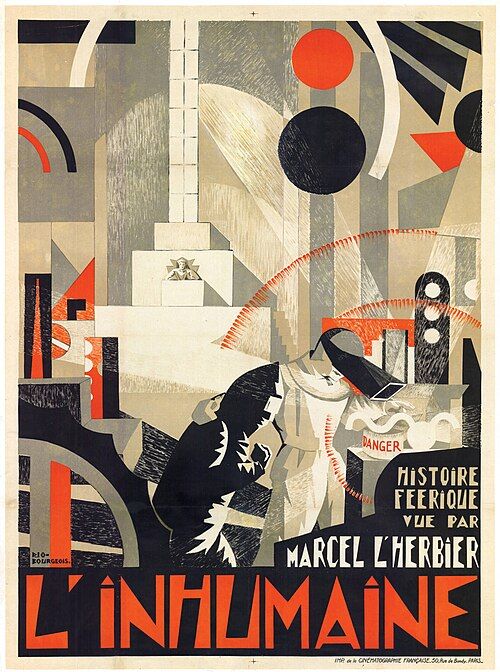

The Inhuman Woman

"A woman without a heart learns to feel through the power of science and art"

Plot

Claire Lescot, a celebrated opera singer living in a futuristic villa on the outskirts of Paris, captivates numerous admirers including a wealthy maharajah and the brilliant young Swedish scientist Einar Norsen. At her lavish parties, she revels in their attention while maintaining an emotional distance, heartlessly toying with their affections and demonstrating her supposed 'inhuman' nature. When news arrives that Norsen has committed suicide due to her cruel rejection, Claire remains coldly indifferent, shocking even her most loyal admirers. During her next performance, the audience, outraged by her perceived heartlessness, boos her off stage, forcing her to confront the consequences of her emotional detachment. This public humiliation leads Claire to visit Norsen's tomb, where she undergoes a profound transformation, ultimately rediscovering her humanity through the scientist's posthumous invention that can capture and replay the essence of human emotion.

About the Production

The film was a collaborative effort between L'Herbier and numerous prominent artists of the time, including architect Robert Mallet-Stevens who designed the futuristic sets, painter Fernand Léger who created mechanical sequences, and composer Darius Milhaud who contributed to the musical score. The production took over a year to complete due to its ambitious artistic vision and technical innovations. The famous laboratory scenes were created in collaboration with actual scientists to ensure authenticity.

Historical Background

The film emerged during the vibrant cultural renaissance of 1920s Paris, a period known as Les Années Folles (The Crazy Years), when France was recovering from World War I and experiencing an explosion of artistic innovation. This era saw the rise of Dadaism, Surrealism, and Art Deco, all of which influenced the film's aesthetic. The 1920s also witnessed the golden age of French impressionist cinema, with directors like Abel Gance, Jean Epstein, and Marcel L'Herbier pushing the boundaries of cinematic expression. The film's fascination with science and technology reflected contemporary society's ambivalence toward modernization and the machine age. Additionally, the post-war period saw a reevaluation of traditional values and a questioning of human nature, themes central to the film's exploration of emotional detachment and redemption. The international character of the cast and settings also reflected the growing cosmopolitanism of 1920s Paris, which had become a magnet for artists and intellectuals from around the world.

Why This Film Matters

'L'Inhumaine' stands as a pivotal work in the history of avant-garde cinema, representing the synthesis of multiple artistic disciplines into a unified cinematic vision. The film's innovative visual language influenced subsequent developments in European cinema, particularly German Expressionism and later French poetic realism. Its exploration of the relationship between humanity and technology anticipated many science fiction themes that would become prominent in later decades. The collaboration between cinema and other established arts helped legitimize film as a serious artistic medium, paving the way for more experimental works. The film's Art Deco aesthetic had a lasting impact on design and architecture, with Claire Lescot's villa becoming an iconic representation of modernist design principles. Additionally, the film's treatment of female independence and emotional complexity contributed to evolving representations of women in cinema, challenging traditional gender roles of the era. The work remains a testament to the creative possibilities that emerge when different artistic disciplines converge in the service of cinematic expression.

Making Of

The production of 'L'Inhumaine' was a landmark collaboration between cinema and other arts, embodying the concept of 'total art' (Gesamtkunstwerk) popular in early 20th century avant-garde circles. Director Marcel L'Herbier assembled a dream team of contemporary artists: architect Robert Mallet-Stevens created the stunning Art Deco sets that represented modernity and technological progress, while painter Fernand Léger designed mechanical sequences that reflected the machine age aesthetic. The filming process was revolutionary for its time, utilizing multiple cameras, complex lighting setups, and innovative editing techniques. The famous laboratory sequence required the construction of elaborate mechanical props and the use of prisms and mirrors to create abstract visual effects. Georgette Leblanc, a celebrated opera singer, insisted on performing her own musical numbers, which required the production to accommodate her professional schedule. The film's most challenging scene involved the recreation of a scientific experiment where a machine captures human emotions, requiring extensive special effects work that pushed the boundaries of 1920s cinema technology.

Visual Style

The cinematography, led by cinematographers Georges Lucas and Jimmy Berliet, was revolutionary for its time, employing innovative techniques that pushed the boundaries of visual storytelling. The film utilized complex lighting setups to create dramatic contrasts and psychological depth, particularly in the laboratory sequences where geometric patterns and abstract compositions reflected the film's modernist aesthetic. The camera work featured unusual angles and movements, including tracking shots that followed characters through the elaborate Art Deco sets, creating a sense of fluid movement through space. The use of superimposition and multiple exposure techniques allowed for the visualization of psychological states and dream sequences. The film's visual style incorporated elements of Cubism and Futurism, with fragmented compositions and dynamic movement that reflected the machine age aesthetic. The color tinting of different scenes added emotional resonance, with each hue carefully chosen to enhance the narrative and thematic content.

Innovations

The film pioneered numerous technical innovations that would influence cinema for decades. It featured some of the earliest uses of superimposition for psychological effect, creating dreamlike sequences that visualized characters' inner states. The mechanical ballet sequences required complex camera movements and multiple exposures to create abstract patterns of light and motion. The laboratory scenes utilized prisms, mirrors, and special filters to create otherworldly visual effects that represented scientific experimentation. The film also experimented with rapid editing techniques and rhythmic montage, influenced by Soviet montage theory. The production employed elaborate miniature effects and matte paintings to create the futuristic settings. The lighting design was particularly innovative, using multiple light sources and colored gels to create dramatic mood effects. These technical achievements were not merely decorative but served the film's thematic concerns about the relationship between humanity, art, and technology.

Music

The original musical score was composed by Darius Milhaud, one of the leading composers of the French modernist school, incorporating elements of jazz, which was revolutionary for a classical film score of the period. The music featured unconventional instrumentation and rhythmic patterns that reflected the film's modernist themes. For the opera sequences within the film, actual operatic pieces were performed by Georgette Leblanc, drawing on her professional experience as a singer. The soundtrack also included mechanical sounds and experimental audio elements that complemented the film's technological themes. In later restorations, new scores have been composed by contemporary musicians who have sought to honor Milhaud's innovative approach while utilizing modern recording techniques. The film's music represents an important moment in the history of film scoring, demonstrating how cinema could incorporate avant-garde musical concepts to enhance its artistic impact.

Famous Quotes

I am not inhuman. I am simply... undiscovered.

Science can capture the image of a soul, but only art can give it meaning.

In this age of machines, we must remember we are still human.

The greatest tragedy is not death, but living without feeling.

Music is the mathematics of emotion, science is the emotion of mathematics.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence introducing Claire Lescot's futuristic villa, with its sweeping camera movements and Art Deco architecture that established the film's modernist aesthetic

- The mechanical ballet sequence in the laboratory, where abstract patterns of light and motion create a hypnotic visualization of scientific experimentation

- The concert scene where Claire is booed by the audience, featuring dramatic close-ups and rapid editing that convey her psychological breakdown

- The climactic scene in the tomb where Claire experiences emotional transformation through the scientist's invention, utilizing superimposition and symbolic imagery

Did You Know?

- The film's original French title 'L'Inhumaine' translates to 'The Inhuman Woman' or 'The Inhuman One'

- Georgette Leblanc, who played Claire Lescot, was actually a famous opera singer in real life, adding authenticity to her performance

- The futuristic villa designed by Robert Mallet-Stevens became an iconic example of Art Deco architecture and influenced many subsequent designs

- Fernand Léger, the famous Cubist painter, created the mechanical ballet sequences that appear in the film's laboratory scenes

- The film featured one of the earliest uses of superimposition techniques to create dream sequences and psychological effects

- Claire Lescot's costumes were designed by Paul Poiret, a leading French fashion designer of the era

- The film was initially criticized for being too avant-garde but later recognized as a masterpiece of French impressionist cinema

- Darius Milhaud composed original music for the film, incorporating jazz elements which were revolutionary for classical cinema scores

- The maharajah character was played by Philippe Hériat, who later became a renowned novelist under the pseudonym Stephen Hudson

- The film's restoration in the 1990s revealed previously unseen details in the elaborate set designs and special effects

What Critics Said

Initial critical reception was mixed, with some contemporary reviewers finding the film too avant-garde and self-indulgent. Le Figaro criticized its 'excessive modernism' while others praised its artistic ambition. However, influential critics like Louis Delluc recognized its significance in advancing cinematic art. Over time, critical opinion has shifted dramatically, with modern film scholars hailing it as a masterpiece of French impressionist cinema. The film is now studied for its innovative visual techniques, its synthesis of multiple art forms, and its influence on subsequent developments in world cinema. Contemporary critics particularly praise the film's bold visual style, its sophisticated treatment of psychological themes, and its pioneering use of cinematic techniques that would later become standard practice.

What Audiences Thought

The film initially struggled to find a broad audience, appealing primarily to intellectuals, artists, and cinema enthusiasts who appreciated its artistic innovations. General audiences of the 1920s found it challenging and abstract, leading to limited commercial success. However, it developed a cult following among avant-garde circles and was frequently screened at art cinemas and film societies. In subsequent decades, as appreciation for classic and avant-garde cinema grew, the film found new audiences through film festivals, museum screenings, and cinematheque presentations. Modern audiences, particularly those interested in film history and artistic cinema, have embraced the work for its visual beauty and historical significance. The film's restoration and availability on home video have further expanded its reach to contemporary viewers interested in the foundations of cinematic art.

Awards & Recognition

- Medal of Honor, International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts, Paris 1925

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- French Impressionist film movement

- Cubist painting

- Futurist art

- Dadaism

- Surrealism

- Opera and theatrical tradition

- Scientific advances of the 1920s

- Art Deco design movement

- Literary works by Marcel Proust

This Film Influenced

- Metropolis (1927)

- The Blue Angel (1930)

- L'Age d'Or (1930)

- Alphaville (1965)

- Blade Runner (1982)

- The Fifth Element (1997)

- The Science of Sleep (2006)

- The Shape of Water (2017)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored by the Cinémathèque Française, with a major restoration completed in 1996 that utilized original nitrate materials and modern digital technology. While some sequences remain incomplete, the majority of the film survives in good condition. The restored version premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and has been screened at major cinematheques and museums worldwide. The restoration revealed previously unseen details in the elaborate sets and special effects, enhancing appreciation of the film's artistic achievements. Original elements are stored in climate-controlled facilities at the French Film Archives.