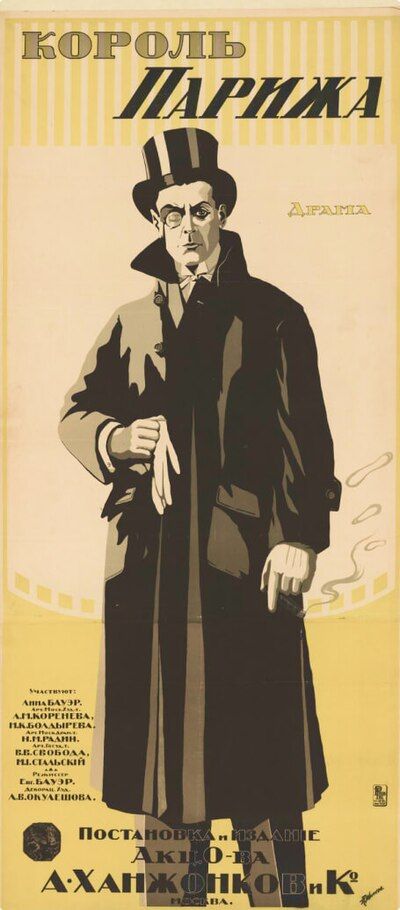

The King of Paris

Plot

The King of Paris tells the story of two young men whose lives dramatically intersect: a virtuous artist who has voluntarily renounced his wealthy background to pursue his craft, and a charismatic swindler who has earned the nickname 'King of Paris' through his elaborate schemes and charm. The conflict intensifies when the artist's mother becomes the target of the sophisticated con artist's latest scheme, forcing the artist to confront the world of deception he had left behind. As the swindler's web of lies grows more intricate, the artist must choose between his peaceful existence and protecting his family from financial ruin. The film explores themes of morality, class, and redemption against the backdrop of Parisian society's glittering facade.

About the Production

Filmed during the tumultuous year of 1917, capturing the final months of the Russian Empire before the Bolshevik Revolution. The production faced significant challenges due to political unrest and resource shortages that affected the film industry during this transitional period.

Historical Background

The King of Paris was produced during one of the most pivotal years in Russian history - 1917. The film was released between the February Revolution, which overthrew Tsar Nicholas II, and the October Revolution, which brought the Bolsheviks to power. This period saw the Russian film industry at its peak, with Russian films being exported internationally and competing successfully with European productions. The cinema of this era often reflected the growing social tensions and class divisions that would soon explode into revolution. The film's themes of wealth, deception, and moral choice were particularly resonant for audiences living through the collapse of the old order. The Russian film industry, which had been one of the world's most innovative and productive, was about to undergo complete transformation under Soviet rule, making films like The King of Paris artifacts of a lost cinematic golden age.

Why This Film Matters

The King of Paris represents the final flowering of pre-revolutionary Russian cinema, which had developed a distinctive style blending European influences with uniquely Russian themes and sensibilities. The film's exploration of moral ambiguity and social critique anticipated the more overt political themes that would dominate Soviet cinema in the following decades. As a work directed by a woman in an era when female directors were extremely rare, it holds special significance in the history of women's filmmaking. The film's sophisticated narrative structure and psychological depth demonstrated the artistic maturity that Russian cinema had achieved by 1917. Its loss represents a significant gap in our understanding of how Russian filmmakers depicted social issues immediately before the Soviet period, making it an important though vanished piece of cinema history.

Making Of

The production of The King of Paris took place under extraordinary circumstances, as Russia was experiencing the complete collapse of its imperial system. The film crew worked in an atmosphere of political uncertainty, with street protests and strikes frequently disrupting shooting schedules. Director Olga Rakhmanova, who had previously worked primarily as an actress, brought a unique perspective to the project, emphasizing character development over spectacle. The cast and crew were paid in rapidly depreciating currency, and many accepted food rations as part of their compensation. Despite these challenges, the production maintained high artistic standards, with elaborate costumes and sets that reflected the opulent Parisian setting. The film's completion was uncertain until the final days, as the studio faced threats of closure from both the provisional government and the emerging Bolshevik authorities.

Visual Style

The film employed the sophisticated visual style that characterized Russian cinema of the 1910s, featuring carefully composed shots and innovative use of lighting to create mood and emphasize psychological states. The cinematographer likely used natural lighting techniques that were becoming popular in Russian studios, along with the use of mirrors and reflections to suggest the dual nature of the characters. The Parisian settings would have been recreated through detailed set design and possibly location photography for establishing shots. The visual narrative would have relied on subtle facial expressions and body language to convey character emotions, a technique at which Russian silent film actors had become particularly adept.

Innovations

While specific technical innovations for The King of Paris are not documented due to the film's loss, Russian cinema of 1917 was known for several technical advances. The film likely employed sophisticated editing techniques including cross-cutting to build suspense and parallel action sequences. The use of multiple camera angles and varying shot distances would have been more advanced than in contemporary American cinema. Russian studios had pioneered the use of location shooting and mobile cameras, which may have been utilized for the Parisian street scenes. The film's production would have benefited from the high technical standards maintained by major Russian studios like Khanzhonkov, which invested in modern equipment and trained technicians.

Music

As a silent film, The King of Paris would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical screenings. The score likely consisted of classical pieces and popular songs selected by the theater's musical director to match the film's moods and dramatic moments. Russian theaters of this period often employed small orchestras or skilled pianists who could adapt their performance to the on-screen action. The music would have ranged from light, sophisticated pieces for the Parisian scenes to dramatic, tension-building compositions during moments of confrontation and revelation. The choice of music would have been crucial in establishing the film's tone and helping audiences navigate its complex moral themes.

Famous Quotes

In Paris, even kings can be made from nothing but charm and courage

An artist's soul is worth more than all the gold in the world

When you dance with the devil, the music never stops

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic confrontation between the artist and the King of Paris in the opulent Parisian salon, where truth and deception finally collide

- The opening sequence contrasting the artist's humble studio with the swindler's luxurious lifestyle

- The emotional scene where the artist discovers his mother has become the swindler's latest target

Did You Know?

- This was one of the last films produced by the Khanzhonkov Film Company before the nationalization of the Russian film industry following the Bolshevik Revolution

- Director Olga Rakhmanova was one of the few female directors working in the Russian Empire during this period

- The film was released in the same year as both the February and October Revolutions, making it part of the final wave of pre-Soviet cinema

- Like many films from this era, the original negative is believed to have been lost during the political upheavals of the early Soviet period

- The title character 'King of Paris' was based on real-life confidence men who operated in European capitals during the early 20th century

- The film's themes of wealth disparity and social injustice resonated strongly with audiences during the revolutionary year of 1917

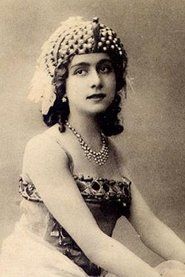

- Emma Bauer, who plays the artist's mother, was a prominent stage actress before transitioning to silent films

- The production used actual Parisian locations for establishing shots, which was unusual for Russian films of this period due to the costs involved

- The film's intertitles were written in both Russian and French to appeal to the growing international market for Russian cinema

- This was one of Nikolai Radin's final film roles before he left the film industry following the revolution

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in Russian film journals praised The King of Paris for its sophisticated storytelling and strong performances, particularly noting Nikolai Radin's charismatic portrayal of the swindler. Critics highlighted the film's moral complexity and the way it avoided simplistic characterizations in favor of nuanced psychological portraits. The cinematography was commended for its elegant composition and effective use of lighting to create atmosphere. Modern film historians have lamented the loss of this film, noting that it represented an important example of the mature, artistically ambitious cinema being produced in Russia during the final years of the imperial period. Had it survived, it would likely be considered a key work in understanding the transition from pre-revolutionary to Soviet cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The King of Paris reportedly found appreciative audiences in major Russian cities, particularly among the educated middle class who could relate to its themes of moral choice and social mobility. The film's Parisian setting and glamorous elements appealed to audiences seeking escapism from the increasingly grim political reality of 1917. Word-of-mouth praise centered on the film's suspenseful plot and the compelling dynamic between the two male protagonists. However, the film's release coincided with such momentous historical events that its theatrical run was likely limited and its impact on popular culture difficult to gauge. The revolutionary upheavals that followed would have dramatically altered audience tastes and priorities, making films like The King of Paris seem relics of a bygone era almost immediately after their release.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- French literary realism

- Russian social novels

- European crime fiction

- Dostoevskian psychological drama

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered lost. Like approximately 90% of Russian films from 1917, no complete copies are known to exist. The revolutionary period and subsequent political upheavals resulted in the destruction of many film archives and private collections. Some production stills and promotional materials may survive in Russian film archives, but the actual film footage has not been located.