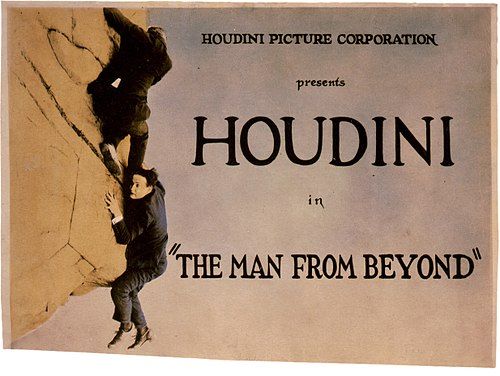

The Man from Beyond

"A Man From Yesterday's World in Today's Romance"

Plot

In the Arctic of 1922, a scientific expedition discovers Howard Hillary frozen in a block of ice, perfectly preserved for exactly one hundred years. After being successfully thawed and revived, Howard struggles to adapt to the modern world of automobiles, telephones, and changing social norms. When he encounters the beautiful Felice Strange, he becomes convinced that she is the reincarnation of his beloved from a century past, creating a complex romantic and mystical dilemma. Howard must navigate his feelings for Felice while dealing with the skepticism of those around him who doubt his extraordinary story and his claims of past-life recognition. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation where Howard must prove his identity and his connection to Felice, leading to a revelation that blurs the lines between coincidence, destiny, and supernatural intervention.

About the Production

The film was produced by Harry Houdini's own production company, giving him complete creative control over the project. Houdini insisted on performing his own stunts, including the ice burial sequence, which required careful coordination and safety measures. The Arctic scenes were created using clever set design and cinematography rather than actual location shooting. The production faced challenges in creating convincing ice effects and maintaining period authenticity for the 1822 sequences. Houdini's involvement extended beyond acting to include script development and promotional planning.

Historical Background

The Man from Beyond was released in 1922, during a fascinating period of transition in American cinema and culture. The film industry was consolidating in Hollywood, though New York remained an important production center, particularly for independent producers like Houdini. The 1920s saw a growing public fascination with spiritualism, the occult, and pseudo-scientific phenomena, themes that Houdini both exploited in his entertainment career and worked to debunk in his personal life. The film's exploration of reincarnation and time travel reflected contemporary interest in these topics, which were popular in literature and film of the period. The year 1922 also saw significant developments in film technology, with longer feature films becoming the norm and more sophisticated special effects being developed. This was also the period when movie stars were becoming major cultural icons, and Houdini was already a celebrity seeking to expand his fame through the new medium of cinema. The film's Arctic setting tapped into the era's fascination with polar exploration, which had captured public imagination through recent expeditions to the North and South Poles.

Why This Film Matters

'The Man from Beyond' represents an important intersection of early cinema history and the career of one of the 20th century's most iconic performers. The film demonstrates how established entertainers from other media sought to leverage their fame in the burgeoning movie industry. Houdini's involvement brought unprecedented attention to independent film production, showing that stars could succeed outside the studio system. The film's themes of reincarnation and supernatural phenomena reflected the cultural tensions between scientific rationalism and spiritual exploration that characterized the 1920s. As one of the few surviving examples of Houdini's film work, it provides valuable insight into how he translated his stage persona to the screen. The film also represents an early example of the time travel/revival genre that would become popular in later science fiction cinema. Its production by an independent company challenged the growing dominance of the Hollywood studio system, showing alternative models for film production were still viable in the early 1920s.

Making Of

The production of 'The Man from Beyond' was deeply influenced by Harry Houdini's hands-on approach to filmmaking. Having worked with major studios like Paramount and Famous Players-Lasky, Houdini decided to form his own production company to have complete control over his projects. The film was shot primarily in New York rather than Hollywood, which was unusual for major productions of the time but allowed Houdini to remain close to his home base and theatrical commitments. The ice sequences required innovative special effects techniques for the era, including the use of glass, wax, and clever lighting to create convincing frozen environments. Houdini insisted on performing his own stunts, including the dangerous ice burial scene, which required careful preparation and safety measures. The cast and crew reportedly had to work around Houdini's busy schedule, as he was simultaneously performing his escape act and conducting investigations into fraudulent spiritualists. The film's production was relatively smooth compared to some of Houdini's other film projects, though there were tensions between Houdini's desire for authenticity and the practical needs of film production.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Man from Beyond' was handled by Arthur Martinelli, who employed innovative techniques to create the film's visual effects, particularly the ice sequences. The Arctic scenes used a combination of practical effects, including glass, wax, and carefully controlled lighting to simulate frozen environments. Martinelli utilized double exposure techniques for some of the supernatural elements, which was advanced for the time. The film contrasts the cold, blue-tinted Arctic sequences with warmer tones for the 1922 contemporary scenes, creating visual distinction between the time periods. Camera work was relatively static, typical of the era, but included some tracking shots during the more action-oriented sequences. The film made effective use of close-ups, particularly for Houdini's performance, helping to convey the emotional aspects of his character's predicament. The cinematography successfully supported the narrative's fantastical elements while maintaining a sense of realism that helped ground the story.

Innovations

The film featured several technical innovations for its time, particularly in the creation of convincing ice and frozen effects. The production team developed new techniques for simulating ice using combinations of glass, wax, and lighting effects that created realistic frozen environments on studio sets. The time-lapse sequences showing Howard's revival from ice were accomplished through careful editing and in-camera effects that were sophisticated for 1922. The film also employed early forms of makeup effects to create the appearance of a man who had been frozen for a century. The production used multiple camera setups for some scenes, which was still relatively uncommon in 1922 and allowed for more dynamic editing. The film's Arctic sequences required innovative set construction that could withstand the heat of studio lights while maintaining the appearance of ice and cold. These technical achievements contributed to the film's visual impact and helped sell its fantastic premise to audiences.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Man from Beyond' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibition. The original score was composed by James C. Bradford, who created a full orchestral score that was distributed to major theaters. The music included romantic themes for the scenes between Howard and Felice, mysterious and suspenseful passages for the reincarnation elements, and dramatic music for the ice sequences. Smaller theaters might have used a reduced version of the score or relied on a pianist or organist to improvise accompaniment based on cue sheets provided by the production company. The score incorporated popular musical styles of the early 1920s while also using more classical motifs for the historical sequences. Unfortunately, the original score has not survived in complete form, though some musical cues and themes have been reconstructed from archival materials and contemporary accounts of the film's exhibition.

Famous Quotes

A hundred years in the ice, but your face has not changed.

You may call me mad, but I know what I know, and I know you.

Science can explain how I survived, but not why I was meant to find you.

The world has changed, but some things remain the same - like love.

I am a man from beyond, but my heart is still human.

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic ice burial sequence where Howard Hillary is discovered frozen in a block of Arctic ice, featuring impressive special effects for the era

- Howard's revival scene where he gradually awakens to find himself in a completely transformed world

- The first meeting between Howard and Felice where he immediately recognizes her as his lost love from a century past

- The climactic confrontation where Howard must prove his identity and his connection to Felice to skeptical characters

Did You Know?

- This was one of the last films Harry Houdini made before retiring from acting to focus on his escape performances and debunking spiritualists

- Houdini formed his own production company specifically to maintain creative control over his film projects

- The ice burial sequence was inspired by one of Houdini's real escape acts, though the film version was dramatically enhanced

- The film explores themes of reincarnation, which Houdini publicly denied believing in despite his interest in spiritual phenomena

- Co-star Arthur Maude was also a director and helped with second-unit direction on the film

- The original story was written by Houdini himself, though it was adapted for the screen by professional screenwriters

- The film's success led to plans for a sequel that was never produced due to Houdini's death in 1926

- Some scenes were shot at the former Biograph Studio in the Bronx, which had become available after Biograph's decline

- The film's title was changed several times during production before settling on 'The Man from Beyond'

- Houdini performed a promotional escape from a sealed box at film premieres to generate publicity

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to 'The Man from Beyond' was generally positive, with reviewers praising Houdini's screen presence and the film's imaginative premise. The New York Times noted that 'Houdini brings his usual showmanship to the screen, making the fantastic elements of the story seem plausible through his committed performance.' Variety appreciated the film's technical achievements, particularly the ice sequences, which they described as 'remarkably convincing for the time.' Modern critics have reassessed the film as an interesting artifact of early cinema that showcases Houdini's star power and the era's fascination with supernatural themes. Film historians have noted that while the narrative may seem conventional by modern standards, it was innovative for its time in blending elements of romance, mystery, and speculative fiction. Some contemporary reviewers found the plot melodramatic, but most acknowledged Houdini's charisma carried the film. The film is now regarded as one of the better examples of Houdini's film work, showing more narrative sophistication than some of his earlier productions.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1922 responded enthusiastically to 'The Man from Beyond,' particularly fans of Houdini's escape performances who were eager to see him on screen. The film performed well in major urban markets where Houdini was already a popular attraction through his stage shows and public demonstrations. Moviegoers were reportedly impressed by the film's special effects, especially the ice burial sequence, which many found thrilling and believable. The romantic elements of the story appealed to female audiences, while the adventure and mystery aspects attracted male viewers. The film's success was enhanced by Houdini's promotional activities, which included personal appearances at theaters and escape performances timed with the film's release. However, the film's reception was more muted in smaller markets where Houdini's name recognition was lower. Despite this, the film was considered a commercial success for an independent production and helped establish Houdini Picture Corporation as a viable competitor to the major studios.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given for this film - the Academy Awards had not yet been established

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The influence of spiritualism movements of the 1920s

- Contemporary fascination with Arctic exploration

- Popular reincarnation narratives in literature

- Earlier Houdini film productions

This Film Influenced

- Later time travel and revival films

- Movies featuring protagonists from the past adjusting to modern times

- Films exploring reincarnation themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in incomplete form at several archives including the Library of Congress and the British Film Institute. Approximately 60-70% of the original film exists, with some sequences missing or damaged. Several restoration attempts have been made over the years, with the most complete version available through specialized film archives and some home video releases. The surviving elements show varying degrees of deterioration, typical of nitrate films from this period. Some missing sequences exist only as still photographs or continuity scripts. The film is considered partially lost but viewable, with gaps in the narrative that can be inferred from surviving materials.