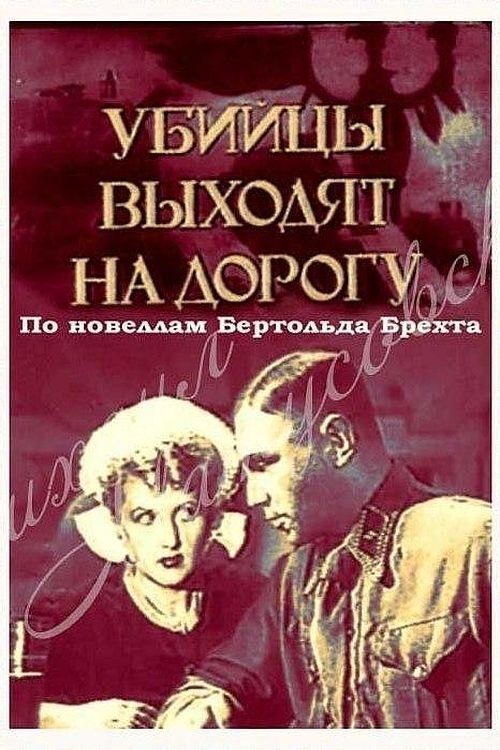

The Murderers Are Coming

Plot

This 1942 Soviet film, directed by Vsevolod Pudovkin, appears to be an adaptation or interpretation of Bertolt Brecht's theatrical work 'Fear and Misery of the Third Reich.' The film presents a series of vignettes depicting life under Nazi Germany, exposing the atmosphere of terror, poverty, and deception that characterized the regime. Through various interconnected sketches, the film portrays how ordinary citizens were crushed under the weight of constant surveillance and ideological oppression. The narrative specifically highlights the brutal antisemitic policies of the Nazi state through segments like 'The Physicist,' 'Judicial Process,' and 'The Jewish Wife,' showing the systematic persecution of Jewish people. As a wartime Soviet production, the film serves as both artistic expression and anti-fascist propaganda, revealing the human cost of totalitarian rule.

About the Production

The film was produced during the critical period of WWII when Soviet cinema was heavily focused on anti-fascist propaganda. Pudovkin, one of the pioneering Soviet montage theorists, adapted Brecht's episodic theatrical structure for the cinematic medium. The production faced significant challenges due to wartime conditions, including resource shortages and the evacuation of film personnel and equipment. Many Soviet film studios were operating under difficult circumstances, with some relocated eastward away from the front lines.

Historical Background

This film was produced during the darkest period of World War II for the Soviet Union, following the devastating German invasion of Operation Barbarossa in 1941. By 1942, Soviet cinema had been completely mobilized for the war effort, with films serving as crucial tools for morale, propaganda, and ideological reinforcement. The adaptation of Brecht's anti-fascist work represents a significant cultural moment, showing how Soviet artists engaged with international anti-fascist literature. The Battle of Stalingrad was raging during the film's production, making its anti-Nazi message particularly urgent. Soviet filmmakers during this period operated under state direction but also with genuine patriotic fervor, creating works that balanced artistic expression with propaganda needs. The film's focus on exposing Nazi brutality resonated with Soviet audiences who were experiencing the reality of German occupation firsthand.

Why This Film Matters

The film represents an important intersection of Soviet cinema and international anti-fascist art during WWII. Its adaptation of Brecht's work demonstrates how Soviet filmmakers engaged with Western artistic traditions while maintaining their own aesthetic principles. The episodic structure and focus on exposing Nazi ideology contributed to the broader Soviet cultural campaign against fascism. As a work from one of the pioneers of Soviet montage theory, it likely represents a mature application of these techniques to contemporary subject matter. The film's portrayal of Nazi antisemitism was particularly significant, as it prefigured later documentation of the Holocaust. Within Soviet cinema history, it stands as an example of how wartime production could maintain artistic ambition while serving ideological purposes. The collaboration between Soviet artists and adaptation of Brecht's work also reflects the wartime cultural alliances between the Soviet Union and Western anti-fascist intellectuals.

Making Of

The making of this film occurred during one of the most desperate periods in Soviet history, following the Nazi invasion of 1941. Pudovkin, already an established master of Soviet cinema, brought his expertise in montage theory to bear on Brecht's episodic structure. The adaptation process would have involved significant cultural translation, as Brecht's German theatrical sensibilities were rendered into Soviet cinematic language. The production team worked under wartime conditions, with constant threat of air raids on Moscow and severe material shortages. Many film industry workers had been conscripted or evacuated, meaning those who remained worked under immense pressure. The casting of prominent actors like Mikhail Astangov and Boris Blinov suggests the film was considered an important propaganda effort. The relationship between Pudovkin and Magarill (who were married) likely influenced the production dynamics, though professional standards in Soviet studios were extremely high regardless of personal relationships.

Visual Style

While specific cinematographic details are not well-documented, Pudovkin's films typically demonstrated sophisticated use of montage and composition. The adaptation of Brecht's episodic structure would have required innovative visual solutions to maintain narrative coherence across different vignettes. Soviet cinematography of the 1940s often balanced artistic expression with clear narrative communication, especially for propaganda purposes. The visual style likely employed dramatic lighting to emphasize the oppressive atmosphere of Nazi Germany. Camera work probably included both intimate close-ups for emotional impact and wider shots to establish the social context. The film may have used documentary-style elements to enhance its authenticity as an exposé of Nazi rule.

Innovations

The adaptation of Brecht's theatrical structure to cinematic form represents a significant technical and narrative achievement. Pudovkin's application of montage theory to contemporary anti-fascist subject matter demonstrates how classic Soviet film techniques evolved to serve wartime needs. The film's episodic structure required innovative editing solutions to maintain narrative flow across different vignettes. Production during wartime conditions with limited resources represented a technical challenge that the crew had to overcome creatively. The visual representation of Nazi ideology and antisemitism required careful consideration of how to depict these themes effectively without being overly didactic. The film likely employed various techniques to create the oppressive atmosphere of 1930s Germany while maintaining Soviet cinematic aesthetic principles.

Music

Specific information about the musical score is not available, but Soviet films of this period typically used orchestral scores to reinforce emotional and narrative elements. The music would have likely emphasized the dramatic tension in scenes depicting Nazi oppression and provided emotional underscoring for moments of resistance or suffering. Soviet composers during WWII often incorporated patriotic themes and folk influences into their film scores. The soundtrack might have included diegetic music that reflected German culture of the 1930s to enhance authenticity. The episodic nature of the film would have required musical themes that could unify the different vignettes while maintaining their distinct identities.

Famous Quotes

Unknown - specific quotes from the film are not well-documented in available sources

Memorable Scenes

- The 'Jewish Wife' segment depicting the impact of Nazi antisemitism on families

- The 'Judicial Process' vignette showing the corruption of Nazi law

- The 'Physicist' scene revealing how intellectual freedom was crushed under fascism

Did You Know?

- Vsevolod Pudovkin was one of the foundational figures of Soviet montage theory, alongside Eisenstein and Kuleshov

- The film represents a rare Soviet adaptation of Western anti-fascist literature during WWII

- Bert Brecht's original play was written in 1938 and first performed in Paris

- The title 'The Murderers Are Coming' may be a Soviet retitle rather than the original adaptation title

- 1942 was a critical year for Soviet cinema, with many films focused on rallying support against the Nazi invasion

- The cast included prominent Soviet actors who were also involved in wartime cultural efforts

- Sofiya Magarill, one of the stars, was married to director Pudovkin at the time

- The film's episodic structure was innovative for Soviet cinema of the period

- Many Soviet films from 1942 were lost or damaged during the war, making surviving prints particularly valuable

- The production likely benefited from state support as part of the Soviet anti-fascist cultural campaign

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critical reception of wartime films was generally positive when they effectively served the anti-fascist cause, though detailed reviews from 1942 are scarce. Critics would have likely praised the film's political message and Pudovkin's directorial skill. Modern film historians have limited access to this work, making comprehensive critical assessment difficult. Those who have studied Pudovkin's wartime work note how his montage techniques evolved to serve more direct narrative purposes during the war. The adaptation of Brecht's theatrical work to cinema would have been of particular interest to critics studying cross-media adaptation. Soviet film criticism of the period was heavily influenced by political considerations, with artistic merit often evaluated through the lens of ideological effectiveness.

What Audiences Thought

Soviet audiences during WWII were hungry for films that clearly depicted Nazi evil and Soviet righteousness, suggesting this film would have been well-received by wartime viewers. The episodic nature of the narrative, adapted from Brecht's play, might have been particularly effective for audiences experiencing war's disruptions. The focus on exposing Nazi antisemitism would have resonated with Soviet citizens, many of whom had witnessed Nazi atrocities firsthand. Wartime audiences often attended films in makeshift venues or as part of mobile cinema units that brought entertainment to soldiers and workers. The emotional impact of seeing Nazi brutality depicted on screen, especially during the height of the German invasion, would have been powerful for Soviet viewers. However, comprehensive audience reception data from 1942 Soviet films is not readily available in modern archives.

Awards & Recognition

- Unknown - Soviet film awards from 1942 are not comprehensively documented

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Bertolt Brecht's 'Fear and Misery of the Third Reich'

- Soviet montage theory

- Socialist realism

- Documentary film traditions

- German expressionism

This Film Influenced

- Unknown - influence difficult to trace due to limited documentation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of this film is unclear - many Soviet films from 1942 were lost or damaged during WWII, and comprehensive archives of this period are incomplete. Some wartime films exist only in fragmentary form or in poor quality prints due to the difficult conditions of production and storage.