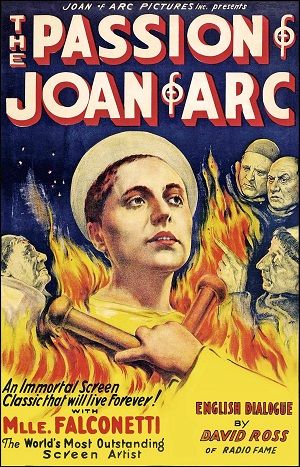

The Passion of Joan of Arc

"The Masterpiece of the Silent Age"

Plot

The Passion of Joan of Arc chronicles the final days of the 15th-century French heroine as she faces trial for heresy before an ecclesiastical court. The film focuses intensely on Joan's spiritual and psychological ordeal as church officials attempt to force her to recant her claims of divine visions and voices. Despite brutal interrogation tactics, torture, and psychological manipulation, Joan maintains her faith and refuses to deny her connection to God, choosing death over betrayal of her beliefs. The film culminates in her martyrdom at the stake, transforming her from a condemned heretic in the eyes of her accusers to a saint in the eyes of history and posterity.

About the Production

Dreyer insisted on shooting in chronological order to maintain emotional intensity. The film was shot with almost entirely close-ups, revolutionary for the time. Maria Falconetti was made to kneel on stone for hours to achieve authentic emotional states. Actors were forbidden to wear makeup to enhance realism. The minimalist set design focused entirely on human drama rather than elaborate scenery.

Historical Background

The film was created during the late 1920s, a period of tremendous artistic experimentation in European cinema, particularly in France and Germany where avant-garde movements were flourishing. This era marked the transition from silent films to 'talkies,' making The Passion of Joan of Arc one of the final masterpieces of the silent era. The film's themes of religious persecution and individual conviction against institutional power resonated deeply with post-World War I audiences who were questioning traditional authorities. The late 1920s also saw growing interest in psychological realism and emotional expression in art, reflected in the film's innovative approach to performance and cinematography. The period's fascination with medievalism and spiritual themes provided fertile ground for Dreyer's exploration of Joan's story.

Why This Film Matters

The Passion of Joan of Arc revolutionized film acting and cinematography, establishing new possibilities for emotional expression through the medium. Its innovative use of close-ups and minimalist storytelling influenced generations of filmmakers, from Ingmar Bergman to Robert Bresson to Martin Scorsese. Maria Falconetti's performance became the benchmark for screen acting, demonstrating the power of subtle facial expressions and emotional authenticity. The film's preservation and rediscovery story has itself become part of cinema lore, highlighting the fragility of film heritage. It continues to be studied in film schools worldwide as an example of pure cinematic storytelling and the potential of the medium to convey profound spiritual experiences. The film's influence extends beyond cinema to theater, photography, and performance art.

Making Of

The production was marked by intense emotional demands on the actors, particularly Maria Falconetti, who Dreyer pushed to her physical and psychological limits. Dreyer's obsessive attention to detail included studying historical documents and consulting with historians to ensure accuracy. The minimalist set design was revolutionary for its time, with Dreyer choosing to focus entirely on the human drama rather than elaborate scenery. The film's distinctive visual style came from Dreyer's decision to use primarily close-ups, creating an intimate and claustrophobic viewing experience. The production faced numerous challenges including budget constraints and skepticism from studio executives who questioned Dreyer's unconventional approach. Dreyer reportedly filmed up to 20 takes of some scenes to achieve the exact emotional intensity he desired.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Rudolph Maté and Joseph-Julien Bagué revolutionized the use of close-up in cinema, creating an unprecedented level of intimacy with the characters. The camera work emphasizes the emotional and psychological states of the characters through careful composition and lighting. The film's visual style is characterized by its minimalist approach, with virtually no establishing shots or wide shots, creating a claustrophobic and intense viewing experience. The innovative use of lighting, particularly the way it illuminates Falconetti's face to express her spiritual and emotional states, influenced countless subsequent films. The cinematography serves the film's theme by making the audience complicit in Joan's suffering and spiritual journey, creating an almost unbearable intimacy with her ordeal.

Innovations

The film pioneered numerous technical innovations that have since become standard in cinema. Its extensive use of close-ups was revolutionary at the time, establishing the technique as a powerful tool for emotional expression. The film's editing rhythm, which alternates between long takes of intense emotional moments and rapid cuts during moments of conflict, created a new language of cinematic expression. The production design, with its minimalist approach to sets and props, demonstrated that emotional intensity could be achieved through performance and cinematography rather than elaborate scenery. The film's preservation and restoration have also contributed to technical knowledge about film preservation techniques, particularly in dealing with nitrate film degradation.

Music

As a silent film, The Passion of Joan of Arc was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater. Over the years, various composers have created scores for the film, including works by Richard Einhorn and Goldfrapp. The most acclaimed modern score is 'Voices of Light' by Richard Einhorn, which was inspired by the film and incorporates medieval music and texts. The absence of synchronized dialogue in the original version enhances the film's universal appeal, allowing the visual storytelling to transcend language barriers. The power of the film's images is such that it can be watched without any musical accompaniment and still maintain its emotional impact, though proper musical accompaniment enhances the spiritual dimensions of the work.

Famous Quotes

"I am not afraid... I was born to do this." (intertitle)

"God has made me a messenger for the kingdom of France." (intertitle)

"One life is all we have, and we live it as we believe in living it." (intertitle)

"I would rather die than do something that I know to be a sin." (intertitle)

"My voices do not command me to disobey the Church." (intertitle)

Memorable Scenes

- The final execution sequence with the camera focusing on the faces of the crowd witnessing Joan's martyrdom

- Joan's moment of breaking under torture and signing the recantation, only to immediately tear it up

- The haircut scene where Joan's femininity is symbolically stripped away along with her hair

- The opening scene with the judges' faces filling the screen, establishing the film's confrontational style

- Joan's silent scream of agony as she witnesses the flames approaching

- The moment when Joan sees the cross held up by a sympathetic soldier in the crowd

Did You Know?

- Maria Falconetti gave what is widely considered one of the greatest performances in cinema history, yet she never appeared in another film.

- The film was thought lost for decades after the original negative was destroyed in a fire in 1928.

- A complete print was miraculously found in 1981 in a mental institution in Oslo, Norway, in the janitor's closet.

- Dreyer made Maria Falconetti kneel on stone for hours during filming to achieve authentic emotional states.

- The film contains no establishing shots, focusing almost entirely on close-ups of the characters' faces.

- The original script was heavily based on actual trial transcripts from 1431.

- The film was banned in Britain for its 'brutal' content and wasn't shown there until 1954.

- Only two copies of the original version existed before they were destroyed in the studio fire.

- Dreyer fired his original cinematographer and hired Rudolph Maté mid-production to achieve his vision.

- The judges in the film were played by professional actors who had never appeared in films before.

What Critics Said

Initial critical reception was mixed, with some reviewers finding the film's intensity and unconventional style difficult to appreciate. However, over time, critical opinion has shifted dramatically, and the film is now universally regarded as a masterpiece. Pauline Kael described it as 'perhaps the most moving film ever made,' while Roger Ebert included it in his 'Great Movies' collection, calling it 'a masterpiece of emotional intensity.' The film consistently ranks among the greatest films ever made in polls of critics and filmmakers, placing 8th in the 2022 Sight & Sound critics' poll. Contemporary critics particularly praise its timeless emotional power and formal innovation, with many noting how its impact has not diminished nearly a century after its creation.

What Audiences Thought

The film initially struggled to find a wide audience due to its challenging subject matter and unconventional style. Many viewers found its intensity overwhelming, particularly the relentless focus on suffering and spiritual torment. However, as the film's reputation grew over the decades, it developed a devoted following among cinema enthusiasts and art film audiences. Modern audiences, accustomed to more rapid pacing and conventional narrative structures, sometimes find the film demanding but ultimately rewarding. The film's power has not diminished over time, and it continues to move audiences deeply when screened in theaters with live musical accompaniment. Online film communities consistently rank it among the most emotionally powerful viewing experiences in cinema history.

Awards & Recognition

- Voted one of the ten greatest films of all time by Sight & Sound magazine poll (1952)

- Included in the Vatican's list of 45 'great films' for artistic merit and moral values (1995)

- Preserved in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress (2018)

- Voted the 8th greatest film of all time in the 2022 Sight & Sound critics' poll

- Received the Danish Film Institute's honorary award for cultural significance (1995)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- Medieval passion plays

- Danish Lutheran tradition

- European realist cinema movement

- Classical tragedy

- Religious art and iconography

This Film Influenced

- The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962)

- Persona (1966)

- The Silence (1963)

- Day of Wrath (1943)

- The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007)

- The Last Days of Joan of Arc (1994)

- Ordet (1955)

- The Seventh Seal (1957)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has a remarkable preservation story. The original negative was destroyed in a fire at the studio in 1928, and for decades it was believed that only incomplete versions survived. In 1981, a complete version was discovered in the janitor's closet of a mental institution in Oslo, Norway, where it had been shown to patients in the 1950s. This version, known as the Dreyer-Willumsen version, is now considered definitive. The film has been beautifully restored and is preserved in the archives of the Danish Film Institute. It was added to the National Film Registry in 2018 for its cultural and historical significance.