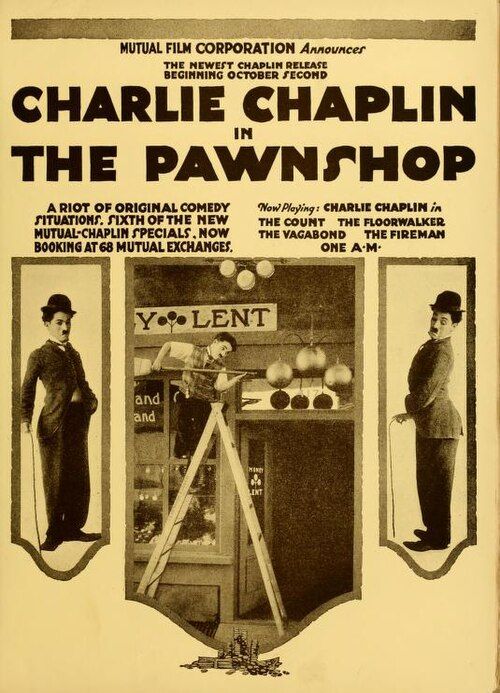

The Pawnshop

"Chaplin's latest Mutual comedy - A masterpiece of mirth and mischief!"

Plot

The Pawnshop follows Charlie Chaplin as an incompetent assistant in a pawnshop run by a grumpy pawnbroker (Henry Bergman) who constantly berates him for his mistakes. Chaplin's character spends his time creating chaos in the shop while attempting to woo the pawnbroker's beautiful daughter (Edna Purviance), who works as the cashier. The film features a series of comedic vignettes as various eccentric customers bring in unusual items to pawn, including a man with a grandfather clock that Chaplin accidentally destroys and another customer with a trombone that becomes a source of musical mayhem. The tension escalates when Chaplin engages in a slapstick battle with his co-worker over a ladder, leading to destruction throughout the shop. The climax arrives when a disguised thief enters the pawnshop with intentions to rob it, leading to a chaotic chase sequence where Chaplin, despite his earlier incompetence, manages to thwart the robbery and save the day, ultimately winning the admiration of both the pawnbroker and his daughter.

About the Production

The Pawnshop was the seventh of twelve films Chaplin produced for Mutual Film Corporation during his most creatively productive period. The film was shot over approximately three weeks in August 1916, with Chaplin meticulously planning each gag and sequence. The elaborate pawnshop set was built specifically for this production and featured numerous props and items that Chaplin could interact with for comedic effect. Chaplin insisted on multiple takes to perfect his timing, which was unusual for the rapid production schedules of the era. The clock destruction sequence alone reportedly required over 20 takes to achieve the desired comedic effect.

Historical Background

The Pawnshop was produced during a pivotal period in American cinema history, 1916, when the film industry was transitioning from short one-reel films to more substantial multi-reel features. This was the height of the silent film era, with comedy being one of the most popular genres. The United States was in the midst of World War I (though still neutral at the time of release), and films provided both escapism and social commentary for audiences dealing with the uncertainty of the period. The pawnshop setting resonated with contemporary audiences as pawnshops were common institutions in urban areas, especially among working-class and immigrant communities who often relied on them during financial hardship. The film reflected the growing sophistication of American comedy, moving away from simple slapstick toward more nuanced character-driven humor. 1916 was also a year of significant labor unrest in the United States, and the film's depiction of the contentious relationship between the pawnbroker and his employees subtly reflected these tensions.

Why This Film Matters

The Pawnshop represents a crucial evolution in cinematic comedy, demonstrating how Chaplin transformed simple slapstick into sophisticated social commentary. The film established many conventions that would become standard in comedy filmmaking, including the use of elaborate sets as playgrounds for physical comedy and the development of character-driven humor that audiences could emotionally connect with. The film's portrayal of working-class life and economic struggle, while comedic, carried undertones of social realism that would become more pronounced in Chaplin's later work. The Pawnshop influenced generations of comedians and filmmakers, from Buster Keaton to Jacques Tati, who studied Chaplin's timing and use of props. The film also demonstrated the commercial viability of comedy shorts as art forms, helping establish comedy as a respected genre rather than mere entertainment. Its preservation and continued study have made it an important teaching tool for film students studying the evolution of cinematic comedy and physical performance.

Making Of

The making of The Pawnshop exemplified Chaplin's perfectionist approach to comedy filmmaking. Unlike many of his contemporaries who would shoot quickly and move on, Chaplin would spend days perfecting individual gags. The famous clock sequence, where Chaplin pretends to be an expert watchmaker while systematically destroying the timepiece, was rehearsed extensively. Chaplin would often work late into the night refining his timing and movements. The set design was particularly elaborate for a two-reel comedy, with the pawnshop filled with authentic props that Chaplin could interact with. Henry Bergman, besides playing the pawnbroker, also appeared in disguise as one of the customers, demonstrating Chaplin's practice of using trusted collaborators in multiple roles. The film's production coincided with Chaplin's growing fame and his increasing battles with the Mutual studio over creative control, though The Pawnshop was made during a relatively harmonious period of their relationship.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Pawnshop, credited to Roland Totheroh and William C. Foster, demonstrates the sophisticated visual style that characterized Chaplin's Mutual films. The camera work is notably more dynamic than typical comedies of the era, with carefully composed shots that maximize the comedic potential of each scene. The pawnshop set was designed to allow for deep focus photography, enabling Chaplin to stage complex action in both foreground and background simultaneously. The film uses a variety of camera angles and movements that were innovative for the time, including tracking shots during the chase sequence and carefully timed zooms to emphasize key comedic moments. The lighting design creates a realistic atmosphere while ensuring that Chaplin's expressive face remains clearly visible throughout. The cinematography particularly shines during the clock sequence, where close-ups capture the intricate details of Chaplin's 'repair' work while wider shots show the growing frustration of the customer.

Innovations

The Pawnshop showcased several technical innovations that advanced the art of comedy filmmaking. The film's use of a fully constructed three-dimensional set rather than flat backdrops allowed for more complex staging and camera movement. The elaborate props, particularly the grandfather clock and trombone, were specifically designed to break and reassemble in comedic ways, demonstrating sophisticated prop engineering. The film's pacing and editing, supervised by Chaplin, created a rhythm that influenced comedy editing for decades. The chase sequence at the film's climax employed innovative camera techniques to maintain visual clarity during fast-paced action. The film also demonstrated advanced understanding of continuity editing, with gags that required precise timing across multiple shots. The destruction of the clock required careful coordination between Chaplin's performance and special effects, showing early mastery of practical effects in comedy.

Music

As a silent film, The Pawnshop was originally accompanied by live musical performance in theaters, typically with a pianist or small orchestra. Chaplin himself composed specific musical cues for his films, though original scores for individual Mutual shorts have not survived. Modern restorations typically feature newly composed scores that attempt to capture the spirit of the period. The film's comedic rhythm suggests a lively, syncopated accompaniment with musical motifs for different characters and situations. The trombone sequence would have been particularly effective with live musical accompaniment, as theaters could incorporate actual brass instruments to complement the on-screen action. Contemporary screenings often feature scores by composers like Carl Davis or Timothy Brock, who specialize in silent film accompaniment. The absence of dialogue enhances the physical comedy, allowing Chaplin's expressive performance to communicate emotion and humor without verbal explanation.

Famous Quotes

(Title card) 'Charlie - The Assistant' - introducing Chaplin's character

(Title card) 'The Pawnbroker - A man of business' - introducing Henry Bergman's character

(Title card) 'His Daughter - The cashier' - introducing Edna Purviance's character

While examining the clock: 'I'll have it fixed in a jiffy!' (expressed through gesture and title card)

During the trombone sequence: (musical chaos with accompanying title card) 'Music hath charms to soothe the savage beast - but not this one!'

Memorable Scenes

- The clock destruction sequence where Chaplin pretends to be an expert watchmaker while systematically dismantling a customer's grandfather clock, pulling out gears and springs with exaggerated precision while the customer grows increasingly anxious

- The ladder battle between Chaplin and his co-worker that escalates into complete chaos, destroying numerous items in the shop

- The trombone sequence where Chaplin attempts to demonstrate the instrument to a customer, producing increasingly discordant sounds

- The final chase sequence where Chaplin pursues the thief through the pawnshop, using every available prop as a weapon or obstacle

- The opening sequence establishing the pawnshop environment and introducing all the main characters through their interactions with various customers

Did You Know?

- The Pawnshop was one of Chaplin's personal favorites among his Mutual shorts, often screening it for friends and visitors to his studio

- The film features one of Chaplin's most famous gags involving an alarm clock that he systematically dismantles and 'repairs' while a customer waits impatiently

- Henry Bergman, who played the pawnbroker, was a close collaborator of Chaplin's and appeared in dozens of his films, often playing multiple roles in the same production

- The trombone sequence was improvised on set when Chaplin discovered the instrument among the props and decided to incorporate it into the comedy

- Edna Purviance, who played the pawnbroker's daughter, was Chaplin's leading lady in over 30 films and was considered his muse during the 1910s and 1920s

- The film's success led to Chaplin being able to demand even more creative control and higher salaries for his subsequent projects

- The Pawnshop was one of the first Chaplin films to be preserved and restored by the Museum of Modern Art in the 1940s

- A young Jackie Coogan, who would later star in Chaplin's 'The Kid,' reportedly visited the set during filming

- The film's elaborate chase sequence at the end was considered groundbreaking for its complexity and influenced numerous subsequent comedy chase scenes

- The Pawnshop was originally titled 'The Pawnbroker's Assistant' but was shortened before release for marketing purposes

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised The Pawnshop as one of Chaplin's finest Mutual shorts, with Motion Picture News calling it 'a masterpiece of comic invention' and Variety noting that 'Chaplin has outdone himself with this latest effort.' The film was particularly lauded for its elaborate set design and the complexity of its gags, which represented a significant advancement from simpler earlier comedies. Modern critics continue to regard The Pawnshop as a high point of Chaplin's Mutual period, with film scholar David Robinson describing it as 'perfectly constructed comedy that demonstrates Chaplin's mastery of the medium at the peak of his creative powers.' The film holds a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on critical reviews, with particular praise for the clock sequence and the film's pacing. Critics have noted how the film balances pure physical comedy with moments of genuine character development, particularly in the interactions between Chaplin and Edna Purviance.

What Audiences Thought

The Pawnshop was enormously popular with audiences upon its release, playing to packed houses in theaters across the United States and internationally. Audience reaction reports from the era described viewers laughing continuously throughout the film, with particular enthusiasm for the elaborate destruction sequences and Chaplin's interactions with various props. The film's success helped establish Chaplin as the world's biggest movie star, with theaters often advertising 'A New Chaplin Comedy' to draw crowds. International audiences embraced the film despite cultural and language barriers, demonstrating the universal appeal of Chaplin's physical comedy. The film was so popular that it was often held over for multiple weeks in major cities, unusual for a short film of the period. Modern audiences continue to appreciate the film, with it frequently screening at film festivals and revival theaters where it still generates enthusiastic laughter and applause.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Mack Sennett comedies

- French and Italian slapstick traditions

- Music hall and vaudeville performance styles

- Commedia dell'arte character archetypes

- Chaplin's earlier Keystone and Essanay films

This Film Influenced

- Buster Keaton's 'The General' (1926)

- Jacques Tati's 'Playtime' (1967)

- The Three Stooges shorts

- Modern workplace comedies

- Physical comedy sequences in films like 'The Pink Panther' series

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Pawnshop has been well-preserved and is considered to be in excellent condition for a film of its era. The film was among the early Chaplin works preserved by the Museum of Modern Art in the 1940s as part of their pioneering film preservation efforts. A complete 35mm print exists in the Chaplin archives, and the film has undergone digital restoration by the British Film Institute and Cineteca di Bologna. Multiple high-quality versions are available for both archival and commercial use. The film is part of the permanent collections of several major film archives including the Library of Congress, UCLA Film & Television Archive, and the Cinémathèque Française. The preservation status is excellent, with no missing scenes or significant deterioration.