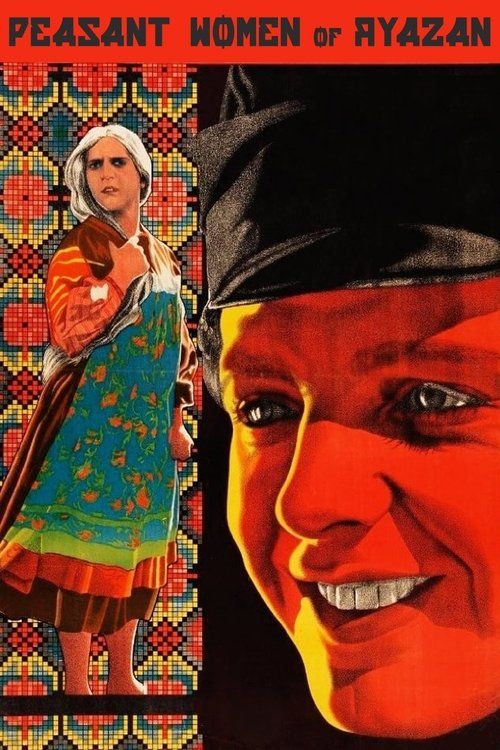

The Peasant Women of Ryazan

Plot

The film contrasts the lives of two peasant women in rural Ryazan province during the early Soviet period. Anna represents the traditional, submissive woman who accepts her fate within the patriarchal structure of village life, while her sister-in-law Vasilisa is rebellious, energetic, and openly challenges the old ways of life. Vasilisa's defiance manifests in her relationships, work ethic, and refusal to conform to traditional gender roles, creating tension within the family and community. The narrative follows both women's journeys as they navigate the changing social landscape following the Russian Revolution, with Vasilisa's path leading to both empowerment and ultimately tragedy, while Anna's conformity offers a different kind of survival. The film serves as a powerful commentary on women's roles in transitional Soviet society and the conflict between tradition and modernity in rural Russia.

About the Production

The film was shot on location in actual peasant villages to ensure authenticity, with many local non-professional actors appearing in supporting roles. Director Olga Preobrazhenskaya insisted on extensive research of rural life and customs, spending months in Ryazan province before filming began. The production faced challenges from Soviet authorities who were concerned about the film's critical portrayal of rural life, but Preobrazhenskaya defended her artistic vision.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period in Soviet history, coinciding with Stalin's consolidation of power and the beginning of the First Five-Year Plan. The late 1920s saw intense debate about the future of Soviet cinema, with advocates like Eisenstein promoting montage theory while others championed more narrative-driven approaches. The film emerged from the relatively liberal period of the New Economic Policy (NEP), which allowed for greater artistic experimentation before Stalinist aesthetic doctrines were fully enforced. The depiction of rural life was particularly significant, as the Soviet government was beginning to implement forced collectivization of agriculture. The film's focus on women's roles reflected the early Soviet emphasis on gender equality, though this would become more complicated under Stalin's regime. The tension between tradition and modernity portrayed in the film mirrored the broader conflicts occurring throughout Soviet society as the country underwent rapid industrialization and social transformation.

Why This Film Matters

The Peasant Women of Ryazan holds a unique place in cinema history as one of the earliest feminist films and a rare example of a woman-directed feature from the silent era. It challenged both traditional gender roles and conventional cinematic storytelling, offering a nuanced portrayal of women's experiences that was uncommon in 1920s cinema. The film influenced later Soviet filmmakers who sought to address social issues through personal narratives rather than overt propaganda. Its international recognition helped establish Soviet cinema's artistic credibility beyond purely revolutionary themes. The film's preservation and restoration have made it an important document for understanding both early Soviet cinema and the history of women in film. Contemporary feminist film scholars frequently cite it as a pioneering work that prefigured later feminist cinema movements. The film also serves as an invaluable historical record of rural Russian life during a period of profound social change.

Making Of

Olga Preobrazhenskaya, one of the few female directors in early Soviet cinema, brought a unique perspective to this production. She spent three months living in Ryazan villages before filming, documenting peasant life and conducting interviews with local women. The casting process was revolutionary for its time - Preobrazhenskaya rejected professional actors in favor of finding performers who embodied the authentic spirit of peasant women. Olga Narbekova's casting as Vasilisa was particularly significant, as she brought a raw, natural energy to the role that Preobrazhenskaya felt professional actors lacked. The director faced significant pushback from Soviet film authorities who wanted a more propagandistic approach, but she insisted on portraying the complex realities of rural women's lives. The film's production coincided with Stalin's rise to power, and its nuanced portrayal of peasant life made it controversial within the increasingly dogmatic Soviet film establishment.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Pyotr Yermolov, employed innovative techniques for its time, including extensive use of natural lighting and location shooting to enhance authenticity. The film features remarkable low-angle shots that emphasize the strength and resilience of the female characters, a revolutionary approach for the 1920s. Yermolov used deep focus compositions to capture the relationship between characters and their environment, particularly the vast Russian landscape. The visual style contrasts the confinement of traditional spaces with the freedom of open fields, mirroring the thematic conflict between tradition and liberation. The film's pacing and visual rhythm were carefully calibrated to build emotional intensity, particularly in scenes of confrontation between the two protagonists. The black and white photography creates stark contrasts that reinforce the film's thematic oppositions between old and new, tradition and progress.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations for Soviet cinema, including the extensive use of location shooting in authentic peasant villages rather than studio sets. Preobrazhenskaya employed innovative editing techniques that emphasized psychological realism over the montage theory popularized by Eisenstein. The film's use of natural lighting and weather conditions to enhance emotional tone was groundbreaking for its period. The production developed new techniques for filming in difficult rural conditions, including portable cameras that could operate in peasant homes and fields. The film's preservation required advanced restoration techniques in the 1980s to repair damage to the original nitrate stock. The cinematography achieved remarkable clarity and depth in outdoor scenes, pushing the technical capabilities of 1920s camera equipment. The film's sound design, though silent, incorporated visual rhythms that anticipated later developments in film editing theory.

Music

As a silent film, the original score was composed by Vladimir Shcherbachov and performed live during screenings. Shcherbachov's music incorporated elements of Russian folk songs and traditional peasant melodies to enhance the film's authenticity. The score used leitmotifs for the main characters - Anna's theme was traditional and melancholic, while Vasilisa's was more dynamic and modern. Contemporary screenings often feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate classical music. The original score was considered lost for decades but was partially reconstructed from surviving orchestral parts in the 1980s. Modern restorations include both the reconstructed original score and newly commissioned works by contemporary composers. The film's sound design, despite being silent, was carefully planned with visual rhythms that would complement musical accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

I will not live as my mother lived. The world has changed, and I must change with it.

Freedom is not given, it must be taken, even if the cost is everything.

In this new world, a woman can be more than just a wife and mother.

The old ways die hard, but die they must.

Your rebellion is your strength, but also your danger in this world.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Anna and Vasilisa working in the fields, immediately establishing their contrasting personalities through their different approaches to labor.

- The dramatic confrontation scene where Vasilisa refuses to participate in a traditional village ritual, challenging the elders and asserting her independence.

- The emotional climax where Vasilisa makes her ultimate choice between personal freedom and family responsibility, set against a vast Russian landscape.

- The final scene showing Anna watching Vasilisa's departure, the camera capturing the complex emotions of envy, admiration, and fear.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the few Soviet films of the 1920s directed by a woman, making Olga Preobrazhenskaya a pioneer in Soviet cinema.

- The film was based on a story by writer Antonina Koptiaeva, who drew from real-life accounts of peasant women in Ryazan province.

- Olga Narbekova, who played Vasilisa, was discovered by Preobrazhenskaya while working as a factory worker in Moscow.

- The film was initially banned in several rural Soviet regions due to its perceived criticism of traditional peasant life.

- It was one of the first Soviet films to explicitly address women's emancipation in rural settings.

- The original negative was nearly destroyed during World War II but was preserved through the efforts of Soviet film archivists.

- Preobrazhenskaya used innovative camera techniques, including low-angle shots to emphasize the strength of her female protagonists.

- The film's international premiere was at the Venice Film Festival in 1934, seven years after its Soviet release.

- Many of the costumes were authentic peasant clothing from the 19th century, sourced from local museums.

- The film was part of a series of 'women's films' that Preobrazhenskaya directed in the late 1920s.

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, Soviet critics praised the film's authentic portrayal of peasant life and Preobrazhenskaya's sensitive direction, though some criticized it for not being sufficiently revolutionary in tone. International critics, particularly in Europe, hailed it as a masterpiece of silent cinema, with French critics comparing it to the works of Flaubert in its detailed social observation. The film's reputation declined during the Stalin era when its nuanced approach was deemed insufficiently propagandistic, but it was rediscovered and reappraised during the Khrushchev Thaw. Modern critics consider it a landmark work of early Soviet cinema, with particular praise for its feminist perspective and innovative visual style. The film is now recognized as one of the most important works by a female director from the silent era and is frequently studied in film history courses worldwide.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary Soviet audiences responded positively to the film, particularly women who identified with the struggles depicted on screen. The film's realistic portrayal of rural life resonated with peasant audiences, though some found its critical elements uncomfortable. In urban centers, the film was appreciated for its artistic qualities and social commentary. International audiences, especially in Europe and America, were impressed by its humanistic approach and technical excellence. The film experienced a revival of interest during the 1960s and 1970s as part of the broader rediscovery of silent cinema. Modern audiences at film festivals and retrospectives continue to respond strongly to its feminist themes and emotional power. The film has developed a cult following among cinema enthusiasts and feminist scholars, who consider it ahead of its time in its treatment of women's issues.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Director at the 1934 Venice Film Festival (Olga Preobrazhenskaya)

- Honorable Mention at the 1935 Moscow International Film Festival

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Works of Maxim Gorky (for realistic portrayal of peasant life)

- Russian realist literature of the 19th century

- Eisenstein's theories of film montage (though the film took a different approach)

- German Expressionist cinema (for visual style)

- Swedish silent films (for naturalistic acting style)

This Film Influenced

- The Earth (1930) by Alexander Dovzhenko

- Happiness (1935) by Medvedkin

- The Ascent (1977) by Larisa Shepitko

- Repentance (1984) by Tengiz Abuladze

- Russian Ark (2002) by Alexander Sokurov

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was preserved in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow, though the original nitrate negative suffered damage during World War II. A major restoration was undertaken in the 1980s by Soviet film archivists, who reconstructed missing scenes from distribution prints found in international archives. The film was digitally restored in 2015 as part of a project to preserve important Soviet silent films. The restored version is now available in high definition and includes both the original Russian intertitles and English translations. Some minor damage remains visible in certain scenes, but the film is considered to be in good preservation condition overall.