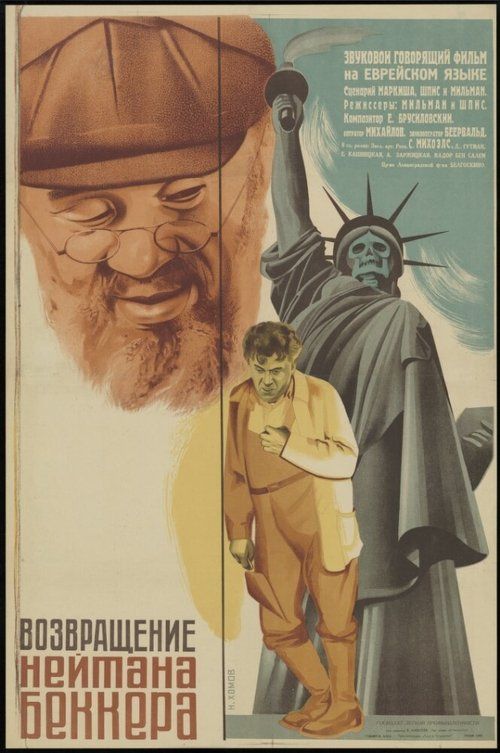

The Return of Nathan Becker

"From the land of opportunity to the land of broken promises"

Plot

Nathan Becker, a Jewish bricklayer living in America during the Great Depression, becomes disillusioned with capitalist society after facing unemployment and discrimination. Inspired by Soviet propaganda promising equality and opportunity, he decides to emigrate to the Soviet Union with his family. Upon arrival, Nathan initially embraces the communist ideals and finds work constructing new buildings in Moscow. However, he gradually discovers the harsh reality of life under Stalin's regime, including forced labor, political purges, and the suppression of religious freedom. The film follows Nathan's growing disillusionment as he witnesses the gap between Soviet propaganda and reality, ultimately leading to a crisis of faith in the system he had idealized.

About the Production

The film was shot during the height of Stalin's First Five-Year Plan and was subject to strict censorship. Director Boris Shpis had to carefully balance the film's critical elements with Soviet propaganda requirements. The production faced significant challenges in depicting authentic Jewish life while adhering to state-mandated artistic guidelines. Many scenes were reshot after initial reviews by Soviet censors who found the original cut too critical of Soviet life.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period in Soviet history, coinciding with Stalin's First Five-Year Plan and the forced collectivization of agriculture. The early 1930s saw massive industrialization efforts, widespread famine, and the beginning of political purges. The Great Depression in America made the Soviet Union appear attractive to many Western intellectuals and workers, leading to a wave of immigration that the film sought to portray. However, the reality of Soviet life during this period was marked by extreme hardship, political repression, and the suppression of minority cultures, including Jewish institutions. The film's production occurred just before the worst years of the Great Purge (1936-1938) and represents a brief window when certain critical themes could still be explored in Soviet cinema. The film also reflects the complex relationship between the Soviet Union and its Jewish population, which oscillated between periods of relative cultural freedom and severe persecution.

Why This Film Matters

'The Return of Nathan Becker' stands as a rare example of early Soviet cinema that dared to question the utopian promises of communism, albeit subtly. It represents one of the few films from this period to explicitly address Jewish identity and the immigrant experience in the Soviet Union. The film's brief release and subsequent banning make it an important historical document of the limits of artistic expression under Stalinism. Its rediscovery and preservation have provided scholars with valuable insights into the tensions between Soviet propaganda and reality during the early 1930s. The film also serves as a memorial to its cast and crew, many of whom became victims of the very system the film critiques. Within the broader context of Jewish cinema, it represents a crucial link between pre-revolutionary Jewish film culture and the suppressed artistic expressions of the Stalin era.

Making Of

The production of 'The Return of Nathan Becker' was fraught with political tension and artistic compromise. Director Boris Shpis, though a party member, struggled to create a film that was both artistically honest and politically acceptable. The casting of Solomon Mikhoels was controversial due to his prominence in the Jewish cultural scene, which was viewed with suspicion by Soviet authorities. The film's screenplay underwent numerous revisions by state censors who demanded more positive portrayals of Soviet life. Despite these pressures, the filmmakers managed to include subtle criticisms of the Soviet system through symbolism and nuanced performances. The bricklaying sequences were particularly challenging to film, requiring the construction of detailed sets and coordination with actual construction projects in Moscow. Many cast and crew members were later arrested during the Great Purge, making the film a haunting document of a doomed artistic generation.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Vladimir Taburin employs a mix of documentary-style realism and expressionist techniques to contrast Nathan's life in America with his experiences in the Soviet Union. The American scenes use darker, shadowy lighting to convey the oppression of capitalism, while the Soviet sequences begin with bright, optimistic shots that gradually become more stark and oppressive. The bricklaying sequences feature impressive long takes that emphasize the physical labor and scale of Soviet construction projects. Taburin makes effective use of Moscow's actual construction sites, creating a powerful documentary feel. The film's visual language evolves from the hopeful compositions of Nathan's arrival to increasingly claustrophobic framing as he discovers the reality of Soviet life.

Innovations

The film pioneered the use of location shooting at actual Soviet construction sites, creating an unprecedented level of realism in Soviet cinema. The production developed new camera mounting techniques to film bricklaying sequences from multiple angles. The sound recording team overcame significant challenges capturing clear dialogue in noisy construction environments. The film's editing, particularly in the montage sequences comparing American and Soviet life, was innovative for its time. The production also experimented with early forms of color tinting for certain symbolic sequences, though only black and white prints survive.

Music

The musical score was composed by Lev Pulver, who incorporated elements of both Soviet socialist realism and traditional Jewish folk music. This fusion was unusual for the period and represented one of the film's subtle acts of cultural resistance. The soundtrack uses leitmotifs to represent Nathan's changing perceptions, with optimistic major-key themes gradually giving way to more dissonant and minor-key compositions. The film features several diegetic musical scenes, including workers' songs and a brief klezmer sequence that was nearly cut by censors. The restored version of the film includes Pulver's complete score, which was partially lost when the film was banned.

Famous Quotes

In America, I was a Jew. In Russia, I am a worker. But in both places, I am a man searching for truth.

They promised us paradise, but they forgot to mention the price of admission.

I left one prison only to find myself in another, this time with better propaganda.

The bricks I lay here are the same as the ones I laid there, but the walls they build feel different.

In the land of equals, some are more equal than others.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Nathan's struggles to find work during the Great Depression, using powerful montage techniques to convey the desperation of the era.

- Nathan's arrival in Moscow, filmed with optimistic lighting and sweeping crane shots that capture the massive scale of Soviet construction projects.

- The tense dinner scene where Nathan first hears Soviet citizens whispering about political purges, using subtle sound design to create an atmosphere of fear.

- The powerful final scene where Nathan stands atop a building he helped construct, surveying Moscow as snow begins to fall, symbolizing his growing disillusionment.

Did You Know?

- Solomon Mikhoels, one of the stars, was a prominent figure in the Moscow State Jewish Theater and would later be murdered by Stalin's secret police in 1948

- The film was banned shortly after its release for being too critical of Soviet conditions, despite its pro-communist premise

- Director Boris Shpis later disappeared during Stalin's purges in the late 1930s

- The film was one of the few Soviet productions of the era to explicitly address Jewish themes and identity

- Original prints were believed destroyed during World War II, but a copy was discovered in the Czech National Film Archive in the 1970s

- The bricklaying scenes featured actual construction workers from Moscow building sites

- The film's title was changed multiple times during production, including 'The American' and 'The Immigrant'

- It was one of the last Soviet films to depict American immigrants before such themes became politically sensitive

- The film's score incorporated elements of Jewish folk music, which was unusual for Soviet cinema of the period

- David Gutman, who played Nathan, had previously worked in Hollywood before returning to the Soviet Union

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics gave the film mixed reviews, with some praising its technical achievements while others criticized its 'bourgeois pessimism.' The official newspaper Pravda initially praised the film's portrayal of American capitalism but later condemned it for 'exaggerating difficulties in socialist construction.' Western critics who saw the film before it was banned noted its powerful performances and courageous storytelling. Modern film historians view the film as a remarkable example of artistic resistance within a totalitarian system, praising its subtle use of symbolism and nuanced character development. The film is now recognized as an important document of its time, valued both for its artistic merits and its historical significance as evidence of the brief period of relative creative freedom in early Soviet cinema before the imposition of socialist realism as the only acceptable style.

What Audiences Thought

Initial Soviet audience reception was reportedly positive, particularly among workers who related to Nathan's struggles. However, the film's limited release and quick banning meant few people actually saw it in theaters. Among the Jewish community in Moscow, the film generated significant discussion due to its rare depiction of Jewish themes in Soviet cinema. American audiences never had the opportunity to see the film during its original release due to political tensions. Modern audiences who have seen the restored version often express shock at its candor and admiration for its artistic courage. The film's rediscovery has made it something of a cult classic among film scholars and those interested in Soviet cinema history.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Jazz Singer (1927)

- October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1928)

- The End of St. Petersburg (1927)

- Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927)

- Strike (1925)

This Film Influenced

- Comrade Mama (1933)

- The Great Citizen (1938)

- The Fall of Berlin (1949)

- Come and See (1985)

- Burnt by the Sun (1994)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for decades after being banned and its prints destroyed. A complete 35mm print was discovered in the Czech National Film Archive in 1972. The film was restored in 1998 by the Gosfilmofond of Russia in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art. The restoration used the Czech print as the primary source, with missing sections reconstructed from surviving fragments and production stills. The restored version includes original Russian intertitles and has been screened at various film festivals and cinematheques. Digital restoration was completed in 2015, making the film available for modern viewing.