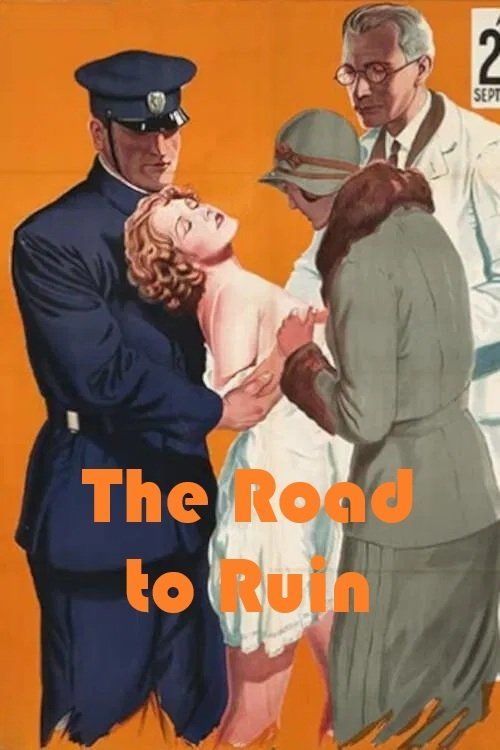

The Road to Ruin

"A Stark Warning of the Perils That Await Modern Youth!"

Plot

Sixteen-year-old Sally Manning, neglected by her wealthy New York parents, descends into a life of vice and moral corruption. After being introduced to smoking and drinking by worldly friends, she engages in a series of affairs with older men who take advantage of her innocence. Her downward spiral culminates in her arrest during a police raid on a strip poker game, followed by her return home where she discovers she's pregnant. After seeking an illegal abortion, the film concludes with the haunting appearance of the words 'The Wages of Sin is Death' materializing in fire above her bed, serving as a moral warning to viewers about the dangers of loose morals and youthful indiscretion.

About the Production

This was a典型的 exploitation film that bypassed the Hays Code by claiming educational value. The production was completed in just 6 days on a shoestring budget. The controversial content, including implied nudity and taboo subjects, was marketed as a 'sex hygiene' film to avoid censorship. The fire effects for the final scene were created using simple double exposure techniques, a common practice in low-budget productions of the era.

Historical Background

Released in 1928, 'The Road to Ruin' emerged during the final years of the silent era and the early days of sound cinema. This period saw the rise of exploitation films that operated outside the mainstream studio system, taking advantage of lax enforcement of censorship codes. The film reflected contemporary anxieties about changing sexual mores, women's liberation, and the perceived moral decay of urban life in the Roaring Twenties. Its release came just before the full implementation of the Hays Code in 1930, which would severely restrict such content in mainstream films. The film also capitalized on the growing concern about 'juvenile delinquency' and the influence of modern city life on traditional values.

Why This Film Matters

'The Road to Ruin' represents an important chapter in American film history as a prime example of the exploitation genre that flourished outside Hollywood's studio system. These films served as a pressure valve for public curiosity about taboo subjects while claiming moral purpose. The film's commercial success demonstrated there was a substantial audience for content too controversial for mainstream theaters. It also influenced the development of later exploitation genres, including teen delinquency films of the 1950s and the 'warning' films of the 1960s. The movie's approach of using moral warnings as a cover for sensational content became a template that would be used for decades in various forms of exploitation cinema.

Making Of

The production of 'The Road to Ruin' was typical of the exploitation film industry of the late 1920s. Shot in less than a week with minimal crew and equipment, the film relied heavily on location shooting in New York to save money on sets. Helen Foster was reportedly paid just $100 for her starring role, but the film's success helped launch her career in similar exploitation pictures. The controversial scenes were carefully choreographed to suggest more than they actually showed, a technique that helped the film avoid outright censorship while still delivering the titillation audiences expected. The production company used the film's notoriety as a marketing tool, sending press releases to newspapers about its 'educational value' while privately promoting its sensational content to theater owners.

Visual Style

The film employed straightforward, functional cinematography typical of low-budget productions of the era. Shot by an uncredited cinematographer, the visual style emphasized clarity over artistry, ensuring that the controversial content would be clearly visible to audiences. The New York location shooting added a degree of realism that contrasted with the more artificial look of studio productions. The fire writing effect in the final scene was achieved through double exposure, a technique that, while simple, proved effective for the film's moralistic conclusion. The camera work during the more suggestive scenes was carefully composed to imply more than it actually showed, using shadows and strategic positioning to suggest nudity without actually showing it.

Innovations

While not technically innovative, 'The Road to Ruin' demonstrated clever low-budget solutions to create its effects. The fire writing sequence used a combination of double exposure and matte techniques that, while simple, proved effective for the film's dramatic conclusion. The production team also employed creative editing to suggest more explicit content than was actually shown, using quick cuts and strategic framing to create the illusion of nudity and sexual situations. The film's use of actual New York locations rather than studio sets gave it a degree of authenticity that enhanced its impact. These technical approaches, while not groundbreaking, were effective in achieving the film's goals within its limited budget.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Road to Ruin' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. Typical of the period, smaller theaters would use a piano player while larger venues might have employed a small orchestra or organist. The musical selections would have been chosen by the theater's musical director to match the mood of each scene - dramatic music for the moral decline, jazz-influenced pieces for the party scenes, and somber themes for the consequences. No original composed score was created for the film, as was common for low-budget productions of this type. When the film was later re-released in the early sound era, some distributors may have added synchronized music tracks or sound effects.

Famous Quotes

"The Wages of Sin is Death" (appears in fire above Sally's bed)

"A pretty face is a dangerous thing in the big city" (opening title card)

"One wrong step leads to another, until the path of virtue is lost forever" (intertitle)

Memorable Scenes

- The infamous strip poker scene where Sally is arrested by police during a raid, considered extremely daring for its time and heavily featured in promotional materials

- The dramatic finale where the words 'The Wages of Sin is Death' appear in supernatural fire above Sally's bed after her abortion, serving as the film's moral conclusion

- The sequence where Sally, neglected by her wealthy parents, is first introduced to smoking and drinking by worldly friends at a sophisticated party

Did You Know?

- This film was one of many 'road to ruin' exploitation films of the 1920s and 1930s that claimed to warn youth about moral dangers while titillating audiences

- Helen Foster, who played Sally, was only 17 years old during filming, barely older than her character

- The film was frequently re-released throughout the 1930s under different titles to maximize profits

- Despite its controversial content, the film managed to avoid significant censorship by claiming educational value

- The strip poker scene was considered extremely daring for its time and was a major selling point in advertisements

- Director Norton S. Parker was actually a pseudonym for the film's producer, who wanted to distance himself from the controversial content

- The film's success spawned numerous imitators and helped establish the 'exploitation film' as a distinct genre

- Many theaters showed this film as a 'special engagement' with separate admission from regular features

- The fire writing effect was achieved through a simple but effective optical printing technique

- The film was banned in several cities but this only increased its notoriety and box office appeal

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics largely dismissed 'The Road to Ruin' as cheap sensationalism, with mainstream publications refusing to review it at all. Trade papers like Variety acknowledged its commercial appeal while condemning its lack of artistic merit. The film was praised only in specialized exploitation industry publications that celebrated its effectiveness in attracting audiences. Modern film historians recognize it as an important artifact of its era, noting how it reflects the social anxieties of the late 1920s and the clever ways producers circumvented censorship. Critics today view it as a fascinating example of how exploitation films both reflected and shaped public attitudes toward sexuality and morality.

What Audiences Thought

The film was surprisingly popular with its target audience of young adults and curious middle-class viewers who were drawn to its taboo subject matter. Many theater owners reported packed houses, especially when the film was marketed with sensational newspaper ads emphasizing its controversial content. Audience reaction was reportedly mixed - some were genuinely shocked by the content, while others found it entertainingly scandalous. The film's notoriety often spread by word of mouth, with many viewers attending specifically to see the infamous strip poker scene. Despite its moralizing ending, many viewers seemed to enjoy the vicarious thrill of watching Sally's descent into vice.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The film was influenced by earlier 'white slave' films of the 1910s

- It drew inspiration from contemporary newspaper stories about juvenile delinquency

- The moral warning structure followed the pattern established by temperance movement films

This Film Influenced

- Numerous 'road to ruin' films of the 1930s

- Teen exploitation films of the 1950s

- The 'warning film' genre of the 1960s

- Modern 'after school special' television programs

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various 16mm and 35mm prints, though quality varies. It has entered the public domain and is available through several archives specializing in exploitation cinema. Some versions are incomplete or missing scenes. The film has been partially restored by film preservation enthusiasts, but no official restoration has been undertaken by major film archives due to its exploitation status.