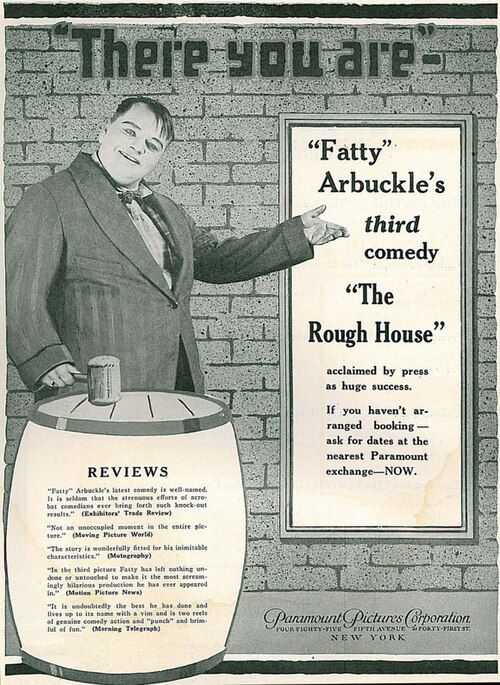

The Rough House

Plot

In this domestic comedy, Mr. Rough lives with his newly-wed wife and interfering mother-in-law in a chaotic household. After carelessly setting the nuptial bedroom on fire, the situation escalates as the resident cook attempts to woo the maid, who only has eyes for the charming delivery boy. When Mr. Rough is forced to prepare dinner for a pair of duplicitous guests, the evening spirals into complete disaster. The dinner party becomes a series of comedic mishaps while Mrs. Rough remains unaware of their guests' true intentions. The film culminates in a spectacular display of domestic chaos as the household's various conflicts and romantic entanglements collide in a memorable finale.

About the Production

The Rough House was produced during the peak collaboration period between Roscoe Arbuckle and Buster Keaton. The film was shot quickly, as was typical for comedy shorts of this era, with minimal takes and significant improvisation. The production utilized real domestic interiors and practical effects, particularly for the fire sequence and kitchen disaster scenes. The film showcases the emerging directorial style of Keaton, who was transitioning from performer to filmmaker during this period.

Historical Background

The Rough House was produced during a transformative period in American cinema and world history. In 1917, the United States was entering World War I, and audiences sought escapist entertainment to offset the tensions of international conflict. The film industry was consolidating in Hollywood, with studios like Comique Film Corporation establishing the star system that would dominate American cinema. Silent comedy was reaching its artistic peak, with performers like Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and the Arbuckle-Keaton team developing sophisticated visual comedy techniques. The domestic comedy genre reflected changing social dynamics as American families navigated modern life, with films like this providing humorous commentary on marriage, in-law relationships, and household management. The film's release coincided with technological advancements in cinematography and film distribution that were making movies more accessible to mainstream audiences.

Why This Film Matters

The Rough House holds significant cultural importance as an early example of the domestic comedy genre that would later become a staple of American entertainment. The film established comedic tropes and scenarios that would influence countless future works, from screwball comedies to modern sitcoms. It represents a crucial moment in the development of physical comedy on film, showcasing how visual humor could transcend language barriers and appeal to diverse audiences. The collaboration between Arbuckle and Keaton demonstrated the effectiveness of ensemble comedy, influencing how comedic teams would be structured in future films. The film's portrayal of domestic chaos and family dynamics resonated with contemporary audiences experiencing similar household tensions, making it both entertaining and relatable. Its preservation of early 20th-century domestic life provides valuable historical insight into American culture during the World War I era.

Making Of

The Rough House represents a pivotal moment in Buster Keaton's career as he transitioned from performer to director. The collaboration between Keaton and Arbuckle was highly creative, with both men contributing gags and refining scenes during shooting. Arbuckle, already an established star and director, mentored Keaton in filmmaking techniques while recognizing his unique comedic talent. The production team worked efficiently, often completing scenes in one or two takes to maintain the spontaneity of the comedy. The physical comedy sequences, particularly the kitchen disaster, required extensive planning and rehearsal to execute safely while maintaining the appearance of chaos. The film's domestic setting allowed for relatable humor while showcasing the performers' athletic abilities and comic timing.

Visual Style

The cinematography in The Rough House was typical of comedy shorts from this period, emphasizing clarity and visibility for physical gags. The camera work was straightforward and functional, using wide shots to capture full-body comedy and medium shots for facial expressions and reactions. The film employed basic tracking shots to follow characters through the chaotic domestic spaces, particularly during the kitchen disaster sequence. Lighting was bright and even, ensuring that all comedic action was clearly visible to audiences. The cinematography prioritized the documentation of physical comedy over artistic experimentation, though the camera placement shows emerging sophistication in framing comedic sequences. The film's visual style supports its narrative by maintaining spatial clarity during complex action scenes.

Innovations

The Rough House demonstrated several technical achievements for its time, particularly in the execution of complex physical comedy sequences. The fire scene required careful coordination of practical effects and performer safety, representing an early example of controlled pyrotechnics in comedy filmmaking. The kitchen disaster sequence showcased advanced understanding of spatial comedy and prop manipulation, requiring precise timing and coordination among multiple performers. The film's editing, while basic by modern standards, effectively built comedic rhythm through the juxtaposition of different characters' reactions to the chaos. The production team's ability to create believable domestic disasters without modern special effects demonstrated considerable ingenuity and technical skill. The film's success in maintaining continuity during complex action sequences represented an important step in the development of visual comedy techniques.

Music

As a silent film, The Rough House originally featured live musical accompaniment that varied by theater and location. Typical scores would have included popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and original improvisations by house pianists or organists. The music would have been synchronized to enhance comedic moments, with faster tempos during action sequences and more romantic themes for the courtship scenes. Modern restorations often feature newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the musical experience of 1917 audiences while incorporating contemporary understanding of film scoring. The absence of recorded sound meant that all comedy had to be visual, making the performers' physical expressiveness even more crucial to the film's success.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) Mr. Rough prepares a dinner that will never be forgotten

(Intertitle) When the cook loves the maid and the maid loves the delivery boy

(Intertitle) A dinner party that goes from bad to worse

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Mr. Rough carelessly sets the bedroom on fire while trying to be romantic

- The extended kitchen disaster sequence where Mr. Rough attempts to cook dinner, resulting in food flying everywhere, dishes breaking, and complete chaos

- The dinner party scene where the duplicitous guests are served the disastrous meal while trying to maintain their composure

- The climactic sequence where all the plotlines converge in a spectacular display of domestic mayhem

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films that Buster Keaton officially directed, though he had been co-directing with Arbuckle on previous projects

- The film was part of the Comique Film Corporation series, which Arbuckle established to give himself creative control

- Keaton's iconic porkpie hat makes an early appearance in this film, though it wasn't yet his signature accessory

- The kitchen disaster sequence required multiple takes due to the complexity of the physical comedy and props

- Al St. John, who plays the cook, was Arbuckle's nephew and a regular in their comedy collaborations

- The film was shot during the summer of 1917 when Hollywood was becoming the center of American film production

- Like many silent comedies, the film featured minimal intertitles, relying primarily on visual storytelling and physical comedy

- The fire scene used practical effects that were considered advanced for the time, requiring careful coordination to ensure safety

- The film's title plays on the double meaning of 'rough' - both the family name and the chaotic nature of the household

- This was one of the last films before Keaton began receiving co-director credit on Arbuckle films

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for The Rough House was generally positive, with trade publications like Variety and Moving Picture World praising the film's comedic timing and physical gags. Critics noted the effective chemistry between Arbuckle and Keaton, recognizing their complementary comedic styles. Modern film historians and critics view the film as an important transitional work in Keaton's career, marking his emergence as a directorial talent. The film is often cited in scholarly works about silent comedy as an example of early domestic slapstick and the development of visual comedy techniques. Critics particularly appreciate the film's efficient storytelling and the way it builds comedic momentum through increasingly absurd situations. The kitchen sequence is frequently highlighted as an early example of Keaton's mastery of complex physical comedy choreography.

What Audiences Thought

The Rough House was well-received by contemporary audiences, who enjoyed its relatable domestic setting and escalating comedic chaos. Moviegoers of the era particularly appreciated the physical comedy and the recognizable family dynamics portrayed on screen. The film's success at the box office helped establish the popularity of the Arbuckle-Keaton collaborations and encouraged further development of the domestic comedy genre. Modern audiences discovering the film through revival screenings and home media continue to find humor in its timeless situations and impressive physical comedy. The film's appeal transcends its silent era origins, with contemporary viewers appreciating the craftsmanship and timing required to execute its complex gags without dialogue.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Vaudeville comedy traditions

- Stage farce

- Mack Sennett comedies

- Charlie Chaplin's early shorts

- Domestic stage plays

This Film Influenced

- The Boat (1921)

- The Cook (1918)

- The Garage (1920)

- The Bellboy (1960)

- Modern sitcoms

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Rough House survives in various film archives and has been preserved by several institutions including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. While not in pristine condition, complete copies exist and have been restored for modern viewing. The film is part of the collection of preserved silent comedies that document the early work of both Arbuckle and Keaton. Some deterioration is visible in existing prints, but the film remains watchable and its comedic content is fully intact. Multiple versions exist with varying degrees of quality, reflecting the film's distribution through different channels during the silent era.