The Sky Pilot

"A Story of the Great Open Spaces and the Greater Human Heart"

Plot

Arthur Moore (John Bowers), a young missionary preacher known as 'The Sky Pilot,' arrives in a rugged western town with the ambitious goal of establishing a church in the local saloon. The skeptical cowboys and townspeople initially reject his efforts, viewing him as an outsider who doesn't understand their way of life. The plot intensifies when Gwen (Colleen Moore), daughter of the respected 'Old Timer' (Harry Todd), suffers a devastating injury during a cattle stampede that leaves her unable to walk. Despite the community's continued resistance, Moore's unwavering faith and genuine compassion begin to win over the hardened locals. Through a series of trials and demonstrations of his wisdom and love, the preacher ultimately helps heal not only Gwen's physical condition but also the spiritual wounds of the entire community, transforming the saloon into a place of worship and redemption.

About the Production

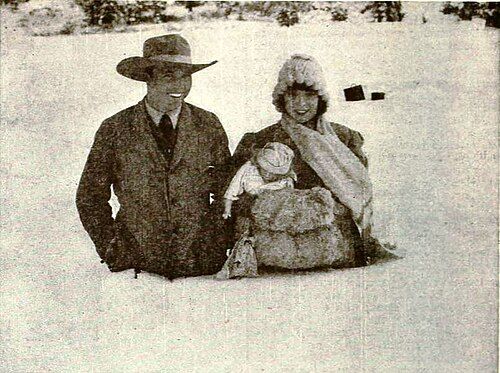

The Sky Pilot was filmed at King Vidor's ambitious but ultimately ill-fated studio complex 'Vidor Village' in the California High Sierra. Vidor had invested heavily in this remote production facility, believing the authentic western landscapes would provide unparalleled backdrop for his films. The production faced numerous challenges including harsh weather conditions, difficult terrain for equipment transport, and isolation from traditional studio resources. The film's mountain location sequences were particularly grueling for cast and crew, with temperatures often dropping dramatically between takes. Despite these hardships, the resulting footage captured breathtaking natural beauty that studio backlots could never replicate. The production was one of the last major films shot at Vidor Village before the facility was abandoned due to financial difficulties and logistical impossibilities.

Historical Background

The Sky Pilot emerged during a pivotal period in American cinema history - 1921 was the year that Hollywood firmly established itself as the world's film capital, with production reaching unprecedented levels. The film industry was transitioning from the chaotic early years to a more structured studio system, though independent producers like Vidor still played a significant role. This was also the height of the western genre's popularity, with audiences hungry for stories of American frontier life and moral clarity. The post-World War I era saw a resurgence of interest in religious and moral themes in popular culture, as society grappled with the changes and disillusionment brought by the war. The film's portrayal of a preacher bringing civilization to the west reflected contemporary ideas about American exceptionalism and manifest destiny. Additionally, 1921 was a year of significant labor unrest in Hollywood, with strikes and unionization efforts affecting many productions. The remote location of The Sky Pilot's production ironically insulated it from many of these industry conflicts, though it created its own set of logistical challenges. The film's release coincided with the beginning of the Roaring Twenties, a period that would soon see dramatic changes in American culture and cinema, making The Sky Pilot somewhat of a transitional work between the moral certainty of the 1910s and the more complex themes that would emerge later in the decade.

Why This Film Matters

The Sky Pilot represents an important transitional work in both King Vidor's career and the evolution of the American western genre. While not as well-remembered as Vidor's later masterpieces like The Big Parade or The Crowd, this film demonstrates his early mastery of location shooting and his ability to blend genre entertainment with deeper moral themes. The film's attempt to merge religious themes with western conventions was relatively innovative for its time, predating the more overtly religious westerns that would become popular in the 1930s and 1940s. Its production at Vidor Village, though financially disastrous, represented an early experiment in location-based filmmaking that would become standard practice decades later. The film also contributed to the rising stardom of Colleen Moore, who would soon become one of the defining flapper icons of the 1920s. Culturally, the film reflected and reinforced early 20th century American ideas about the civilizing mission of religion and the moral superiority of settled society over frontier lawlessness. While some modern viewers might find these themes simplistic or paternalistic, they were mainstream and widely accepted in 1921. The film's preservation and occasional revival screenings offer contemporary audiences a window into the values and storytelling techniques of early Hollywood, demonstrating how the western genre has evolved while maintaining certain core elements.

Making Of

The making of The Sky Pilot was as dramatic as the film itself, centered around King Vidor's ambitious but doomed Vidor Village studio complex. Vidor had invested his personal fortune into building a complete production facility in the remote California High Sierra, believing that authentic locations would revolutionize western filmmaking. The production faced extraordinary challenges - equipment had to be hauled up mountain trails by pack animals, cast and crew lived in primitive camps, and weather conditions could change dramatically within hours. John Bowers, already an established star, took a significant risk by co-producing with Vidor, showing his faith in both the project and Vidor's vision. The cattle stampede sequence required weeks of preparation and was genuinely dangerous, with no computer effects or safety equipment available. The film's difficulties were compounded by the isolation - when problems arose, help was days away. Despite these hardships, or perhaps because of them, the cast developed a strong bond and commitment to the project. The authenticity of the location shooting paid off visually, though the financial costs were devastating. Vidor would later speak of this period as both his most creative and most financially devastating time, lessons that would influence his later, more pragmatic approach to filmmaking.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Sky Pilot, while not credited to a specific cinematographer in surviving records, demonstrates remarkable sophistication for its time, particularly in its use of natural landscapes. The film's most striking visual achievement is its effective use of the Sierra Nevada locations, with sweeping shots of mountain ranges, valleys, and open plains that convey both the beauty and isolation of frontier life. The camera work shows early mastery of depth and scale, with human figures often framed against vast natural backdrops that emphasize their vulnerability and determination. The stampede sequence was particularly innovative for its time, using multiple camera angles and dynamic movement to create genuine tension and excitement. Interior scenes, particularly those in the saloon-turned-church, demonstrate effective use of lighting to create mood and contrast the sacred and secular elements of the story. The film makes excellent use of natural light, particularly in outdoor scenes where the changing mountain light is used to enhance emotional moments. While the surviving prints show some deterioration, they still reveal a visual style that was ahead of many contemporary productions in its integration of location shooting with narrative storytelling. The cinematography successfully supports the film's themes by contrasting the raw power of nature with the civilizing influence of human spirituality.

Innovations

The Sky Pilot's most significant technical achievement was its ambitious location shooting in the remote Sierra Nevada mountains, which was highly unusual for 1921 when most productions were still primarily studio-bound. The successful filming of the cattle stampede sequence with real animals represented a considerable technical and logistical accomplishment, requiring careful coordination and innovative camera placement to capture the action safely. The film demonstrated early mastery of exterior lighting techniques, effectively using natural light to create mood and enhance storytelling. The production's ability to transport and operate film equipment in extremely remote mountain terrain showed remarkable technical ingenuity for the period. The integration of location footage with studio elements was seamless, indicating sophisticated post-production techniques for the time. The film also employed innovative editing techniques, particularly in the stampede sequence, to create tension and narrative clarity. While not groundbreaking in terms of cinematic technology, The Sky Pilot pushed the boundaries of what was possible in location filming during the early 1920s, techniques that would become more common as equipment became more portable and reliable. The film's visual effects, while simple by modern standards, were effective for their time and served the story well.

Music

As a silent film, The Sky Pilot would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific musical score has not been preserved in written form, but theater orchestras of the period typically used a combination of classical pieces, popular songs, and specially composed cues. Given the film's western setting and religious themes, the musical accompaniment likely included cowboy ballads, hymn-like melodies, and dramatic orchestral pieces for action sequences. The transformation of the saloon into a church would have been musically emphasized, probably with a shift from raucous, syncopated music to more solemn, harmonious arrangements. Some theaters might have used popular hymns of the period that audiences would recognize, enhancing the emotional impact of religious scenes. The cattle stampede sequence would have required particularly dynamic and percussive music to build tension and excitement. Contemporary accounts suggest that the film's emotional effectiveness was significantly enhanced by thoughtful musical accompaniment, with many reviewers noting how the music amplified the spiritual themes. Modern screenings of restored silent films typically use newly composed scores that attempt to capture the spirit of the original accompaniment while taking advantage of contemporary musical resources.

Famous Quotes

'A man's faith is tested not in the church, but in the wilderness of the human heart.' - Arthur Moore

'The Lord works in mysterious ways, sometimes through the most unlikely of vessels.' - Old Timer

'This saloon may have seen much sin, but it's never seen prayer.' - Arthur Moore

'In these mountains, a man learns that the greatest strength is not in his guns, but in his spirit.' - Old Timer

'When the cattle run wild and the thunder rolls, that's when you find out what you're made of.' - Cowboy

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic cattle stampede sequence where Gwen is injured, filmed with real cattle and featuring breathtaking wide shots of the chaos in mountain terrain

- The powerful scene where Arthur Moore first enters the saloon and attempts to preach to the skeptical cowboys, gradually winning their attention

- The emotional climax where the transformed saloon is filled with worshipers, demonstrating the preacher's success in bringing spiritual renewal to the community

- The healing scene where Moore's faith and care help Gwen begin to walk again, combining physical and spiritual restoration

- The opening sequence establishing the remote mountain setting and introducing the harsh beauty of frontier life

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films produced at King Vidor's ambitious Vidor Village studio complex, which ultimately proved to be a financial disaster.

- The Sky Pilot was based on a popular 1900 novel by Ralph Connor, which had already been adapted for the stage multiple times before this film version.

- King Vidor and John Bowers formed a production company specifically to make this film, demonstrating Vidor's early entrepreneurial spirit in Hollywood.

- The film's production was so remote that the cast and crew had to live in temporary camps for weeks at a time in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

- Colleen Moore, who played Gwen, would become one of the biggest stars of the 1920s, but this was still relatively early in her career.

- The cattle stampede sequence was filmed using real cattle, making it extremely dangerous for the cast and crew.

- Vidor Village, where the film was shot, was so remote that film had to be transported miles by pack animals to be developed.

- The film's title 'Sky Pilot' was 1920s slang for a preacher or minister, particularly one working in remote or frontier areas.

- Despite the film's modest success, the financial losses from Vidor Village nearly bankrupted King Vidor early in his career.

- The original novel had been a bestseller and was considered controversial for its time due to its portrayal of religious themes in a western setting.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for The Sky Pilot was generally positive, with reviewers particularly praising the authenticity of its mountain locations and the sincerity of its performances. The Motion Picture News noted that 'the magnificent scenery of the Sierras adds a dignity and grandeur to the production that could never be achieved in studio settings.' Variety praised John Bowers' performance as 'earnest and convincing' though some critics felt the religious themes were handled too heavy-handedly. Modern critical assessment has been limited by the film's relative obscurity and availability issues, but film historians who have studied it recognize its importance in Vidor's development as a director. The film is often cited in discussions of early location shooting techniques and the evolution of the religious western subgenre. Critics have noted that while the storytelling may seem simplistic by modern standards, the film's visual composition and use of natural landscapes were quite sophisticated for 1921. The blend of genre entertainment with moral messaging was seen as commercially savvy at the time, though some contemporary reviewers wished for more subtlety in the religious themes. Overall, the film was regarded as a solid, respectable production that succeeded in its goals even if it didn't break new ground narratively.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to The Sky Pilot in 1921 was generally favorable, particularly among moviegoers who appreciated westerns with moral themes. The film found its strongest audience in smaller towns and rural areas where its religious themes and frontier setting resonated most strongly. Contemporary theater reports indicated that the film performed well in midwestern and western markets, though it was less successful in major urban centers on the East Coast. The combination of spectacular scenery, familiar western tropes, and uplifting moral message made it popular with family audiences. Many viewers wrote letters to trade papers expressing appreciation for the film's wholesome content and positive portrayal of religious values. The performance of Colleen Moore was particularly noted by female audience members, who found her portrayal of the injured Gwen both touching and inspirational. However, some audiences found the pacing slow compared to the more action-packed westerns becoming popular at the time. The film's moderate commercial success was hampered somewhat by the limited distribution that First National Pictures could provide compared to the major studios. Despite these challenges, The Sky Pilot developed enough of a reputation to be referenced in subsequent discussions of quality religious films and westerns throughout the 1920s.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards documented for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The novel 'The Sky Pilot' by Ralph Connor (1900)

- Stage adaptations of Ralph Connor's work

- Contemporary religious dramas

- Early western films of the 1910s

- D.W. Griffith's location shooting techniques

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent religious westerns of the 1920s-1940s

- Later King Vidor films dealing with moral themes

- Films combining religious and genre elements

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Sky Pilot is partially preserved with incomplete elements surviving in film archives. While the majority of the film exists, some reels are missing or in poor condition. The Library of Congress holds fragments of the film, and additional material exists in other archives including the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The surviving elements show significant deterioration typical of films from this period, including nitrate decomposition in some sections. Several restoration projects have been attempted over the years, but a complete, fully restored version has not been achieved. The film's status makes it relatively rare for public screening, though film societies and museums occasionally show the surviving fragments. The preservation challenges are compounded by the film's obscure status and lack of commercial viability for major restoration efforts. Film historians continue to search for missing reels in private collections and smaller archives, hoping to eventually complete the film for future generations.