The Snows of Kilimanjaro

"He lived a life of passion... and paid the price!"

Plot

Harry Street, a successful American writer on safari in Africa, lies dying from a thorn scratch that has become dangerously infected. As he languishes in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro, Harry reflects on his life through a series of flashbacks, recalling his failed marriage to first wife Cynthia Green, his affair with wealthy socialite Elizabeth, and his current relationship with devoted Helen who is trying to save him. Tormented by regret over abandoning his literary ambitions for commercial success and wealth, Harry confronts his past mistakes and the choices that led him to this moment. As his condition worsens and rescue seems impossible, Helen desperately tries to keep him alive while Harry struggles to find meaning in his life's work and relationships. The film culminates in Harry's final moments as he gazes toward the snow-covered peak of Kilimanjaro, symbolizing the purity and achievement he never quite attained in life.

About the Production

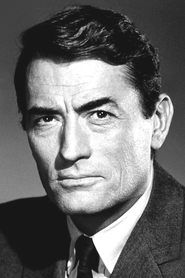

The production faced significant challenges filming in Africa, including extreme weather conditions, difficult terrain, and logistical nightmares transporting equipment to remote locations. Gregory Peck contracted a severe eye infection during filming, nearly causing production delays. The famous snow-capped Kilimanjaro scenes were actually filmed using matte paintings and process photography since the actual mountain was too difficult to access. The African wildlife sequences required careful coordination with local guides and handlers, with some scenes filmed at the Nairobi National Park.

Historical Background

Released in 1952, 'The Snows of Kilimanjaro' emerged during a transitional period in Hollywood, as the studio system grappled with the challenges of television and changing audience tastes. The early 1950s saw increased interest in psychological dramas and films that explored deeper themes of existential angst and personal failure, reflecting the post-war mood of introspection and questioning traditional values. The film's focus on a writer's creative struggles and personal regrets resonated with audiences familiar with the disillusionment that followed World War II. Additionally, the film's African setting reflected America's growing interest in international locations and stories, as the country became more globally engaged following the war. The adaptation of Hemingway's work was part of a broader trend of bringing serious literary works to the screen, as Hollywood sought cultural legitimacy and more sophisticated storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

'The Snows of Kilimanjaro' represents a significant moment in the adaptation of literary modernism to mainstream cinema, bringing Hemingway's distinctive style and themes to a mass audience. The film helped establish the template for the 'literary adaptation' as prestige filmmaking, combining star power with serious themes. Its success demonstrated that audiences would respond to complex, psychologically driven narratives, paving the way for more sophisticated adult dramas throughout the 1950s. The film also contributed to the romantic myth of the expatriate writer and the allure of Africa as a setting for adventure and self-discovery. Ava Gardner's performance particularly influenced the archetype of the femme fatale in 1950s cinema, while the film's visual style helped define the Technicolor aesthetic of the era. The movie's exploration of regret and the cost of artistic compromise remains relevant to contemporary discussions about creative integrity versus commercial success.

Making Of

The production of 'The Snows of Kilimanjaro' was one of the most ambitious Hollywood undertakings of the early 1950s, requiring a massive expedition to East Africa. Director Henry King and his crew spent months in Kenya and Tanganyika, facing extreme conditions including temperatures over 100 degrees, dangerous wildlife, and limited medical facilities. The studio invested heavily in the location shooting, sending tons of equipment, including generators, cameras, and even a mobile film processing lab. Gregory Peck prepared for his role by studying Hemingway's works and meeting with people who knew the author personally. The relationship between Peck and Ava Gardner on set was reportedly tense, as Gardner felt her role was being overshadowed by Hayward's. The film's screenplay went through numerous revisions, with Casey Robinson and John Patrick working to expand Hemingway's brief story into a full-length feature while maintaining the author's themes of regret, lost opportunities, and the conflict between art and commerce.

Visual Style

Leon Shamroy's cinematography for 'The Snows of Kilimanjaro' is widely regarded as one of the finest examples of Technicolor photography in the early 1950s. The film's visual style combines sweeping African landscapes with intimate character moments, creating a rich visual tapestry that enhances the story's emotional depth. Shamroy employed innovative techniques for the time, including extensive use of location shooting in natural light to capture the authentic beauty of the African terrain. The famous Kilimanjaro sequences used groundbreaking matte painting techniques to create the illusion of the snow-capped mountain, seamlessly blending studio work with location footage. The cinematography effectively contrasts the vibrant, sun-drenched African exteriors with the increasingly claustrophobic interior scenes as Harry's condition worsens. The color palette shifts throughout the film, from the warm, romantic tones of Harry's memories to the harsh, clinical whites of his present suffering, visually reinforcing the narrative's themes of memory and mortality.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in location filming and visual effects. The production developed new portable camera equipment and power systems that allowed for filming in remote African locations with minimal infrastructure. The matte painting techniques used for the Kilimanjaro sequences were groundbreaking for their time, creating seamless transitions between studio and location footage. The film also featured innovative sound recording techniques for capturing dialogue in outdoor locations with challenging acoustic conditions. The Technicolor process was pushed to its limits in capturing the contrast between the bright African sunlight and deep shadow scenes, requiring new approaches to exposure and color timing. The wildlife sequences required custom-built camera housings and remote filming techniques to safely capture animals in their natural habitat.

Music

Bernard Herrmann composed the film's musical score, creating a lush, romantic soundtrack that perfectly complemented the African setting and the story's emotional arc. Herrmann's music incorporates African-inspired rhythms and instrumentation while maintaining the sweeping orchestral style characteristic of 1950s Hollywood dramas. The score features recurring leitmotifs for the main characters and themes, with Harry's theme evolving throughout the film to reflect his changing emotional state. The music during the African sequences uses tribal drums and indigenous instruments to create authentic atmosphere, while the romantic scenes are accompanied by sweeping string arrangements. Herrmann's score was particularly praised for its ability to enhance the film's emotional moments without overwhelming the dialogue or performances. The soundtrack was released as a record album and became one of the composer's most popular works from this period.

Famous Quotes

Harry Street: 'I've wasted my life. I've wasted it all.'

Cynthia Green: 'You're not going to die, Harry. You're going to live.'

Helen: 'I love you, Harry. I've always loved you.'

Harry Street: 'The snows of Kilimanjaro... so close and yet so far.'

Harry Street: 'I sold my words, I sold my life.'

Cynthia: 'We had something wonderful, Harry. Something that doesn't happen to many people.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Harry Street lying wounded in the African plain with Mount Kilimanjaro looming in the distance, establishing the film's central visual metaphor.

- The flashback to Harry and Cynthia's passionate love affair in Paris, showcasing Ava Gardner's magnetic screen presence and the film's romantic visual style.

- The dramatic safari sequence where Harry gets infected by the thorn, filmed on location with authentic African wildlife and landscape.

- The emotional confrontation scene between Harry and Helen as she desperately tries to keep him alive, featuring powerful performances by Peck and Hayward.

- The final moments as Harry gazes at Kilimanjaro, with the famous matte painting of the snow-capped mountain representing his unattainable dreams.

Did You Know?

- Ernest Hemingway reportedly hated the film adaptation, particularly the changes made to his original story, though he did appreciate the performances.

- Ava Gardner's role as Cynthia Green was significantly expanded from Hemingway's original story to give the film more romantic drama.

- The snow on Mount Kilimanjaro was created using salt, flour, and gypsum, as filming the actual snow-covered peak was impractical.

- Gregory Peck was Henry King's first choice for the role of Harry Street, having previously worked together on several successful films.

- The film's success at the box office helped 20th Century Fox recover from financial difficulties following the production of 'All About Eve'.

- Susan Hayward was initially reluctant to take the role of Helen, feeling it was too similar to other parts she had played.

- The African sequences were some of the first major Hollywood productions filmed on location in post-colonial Africa.

- The film's famous line about the leopard on Kilimanjaro was added by screenwriter Casey Robinson, not from Hemingway's original story.

- The production used over 500 African extras and local crew members during the location filming.

- The film's Technicolor cinematography was particularly praised for its vivid rendering of the African landscape.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'The Snows of Kilimanjaro' for its ambitious scope and visual splendor, with particular acclaim for Leon Shamroy's cinematography and the performances of the three leads. The New York Times' Bosley Crowther noted that 'the picture has a rich, pictorial quality and a dramatic intensity that is compelling.' However, some critics felt the film was overly sentimental and had diluted Hemingway's original work. Modern critics have reassessed the film more favorably, appreciating its place in the canon of 1950s prestige dramas and its successful blend of adventure elements with psychological depth. The film is now recognized as one of the better Hemingway adaptations, despite the author's own objections to the changes made to his story. The performances, particularly Peck's portrayal of the tormented writer and Gardner's enigmatic Cynthia, are frequently cited as among the actors' finest work.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a major commercial success upon its release, resonating strongly with 1950s audiences who were drawn to its combination of adventure, romance, and serious themes. Moviegoers particularly responded to the exotic African setting and the star power of Gregory Peck, Susan Hayward, and Ava Gardner. The film's themes of regret and redemption struck a chord with post-war audiences, many of whom were grappling with their own questions about life choices and missed opportunities. The movie's box office success helped establish it as one of the year's biggest hits and solidified the market for adult-oriented dramas with literary origins. Audience word-of-mouth was particularly positive regarding the film's emotional impact and visual spectacle, with many viewers citing the African sequences and the final scenes as particularly memorable. The film has maintained a devoted following among classic film enthusiasts and continues to be appreciated for its ambitious storytelling and star performances.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award for Best Cinematography (Color) - Winner

- Academy Award for Best Art Direction (Color) - Winner

- Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role - Ava Gardner - Winner

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Ernest Hemingway's original short story

- The Lost Generation literature

- Film noir visual style

- Hollywood prestige dramas of the 1940s

- African adventure films of the era

This Film Influenced

- Mogambo (1953)

- The African Queen (1951)

- Out of Africa (1985)

- The Last Safari (1967)

- White Hunter Black Heart (1990)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the 20th Century Fox archives and was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 2021 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. A restored version was released on Blu-ray in 2015 as part of the Fox Studio Classics collection, featuring a new 4K transfer from the original Technicolor negatives. The restoration work included color correction to match the original theatrical presentation and digital cleanup of damage and deterioration.