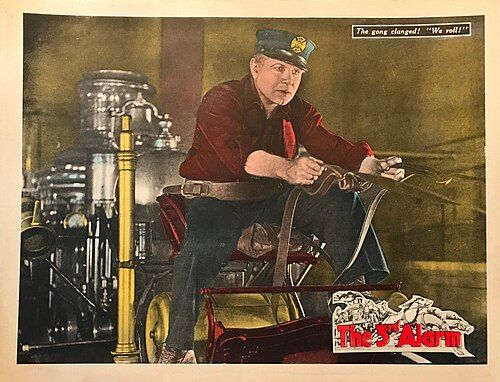

The Third Alarm

"A Story of the Fire-Fighting Bravest!"

Plot

In this emotional drama, veteran firefighter Dan McDowell faces retirement when he's unable to adapt to the new mechanized fire equipment, receiving only a meager pension. His devoted son Johnny quits school to join the fire department to help support the family, while Dan's loyal horse Bullet, who served alongside him for years, is cruelly sold to a dirt-hauler. When Dan is wrongfully accused of stealing Bullet back from his new owner, he faces imprisonment and disgrace. However, Dan is eventually cleared of all charges just in time to provide crucial assistance during a devastating fire that traps Johnny's sweetheart, June Rutherford, demonstrating that old-fashioned courage and experience still have value in the modern world.

About the Production

The film featured real fire department equipment and locations, with cooperation from local fire departments. Director Emory Johnson was known for his realistic action sequences and often used authentic settings and equipment in his films. The production faced challenges in staging realistic fire scenes safely during the silent film era.

Historical Background

The Third Alarm was produced during a transformative period in American firefighting, as departments across the country were transitioning from horse-drawn equipment to motorized apparatus. This technological shift created real social tensions similar to those depicted in the film, with many veteran firefighters facing retirement or unemployment due to their inability or unwillingness to adapt to new systems. The 1920s also saw the rise of the feature-length silent film as America's dominant form of entertainment, with movies increasingly addressing contemporary social issues. The film's release in 1922 came just before the boom years of the Roaring Twenties, when urbanization and industrialization were rapidly changing American life.

Why This Film Matters

While not a major box office success, 'The Third Alarm' represents an early example of cinema addressing the social impact of technological advancement on working-class Americans. The film tapped into public fascination with firefighters, who were widely regarded as urban heroes during the early 20th century. It also contributed to the emerging genre of workplace dramas that explored the human cost of industrial progress. The movie's sympathetic portrayal of an aging worker facing obsolescence resonated with audiences experiencing similar changes in various industries during this period of rapid modernization.

Making Of

The production of 'The Third Alarm' was notable for its commitment to authenticity. Director Emory Johnson, who had a reputation for realism in his action films, worked closely with actual fire departments to ensure accurate depictions of firefighting procedures and equipment. The film's fire scenes were particularly challenging to create safely in the early 1920s, requiring innovative techniques involving controlled burns and special effects. The cast underwent some basic firefighting training to make their performances more convincing. Ralph Lewis, who played Dan McDowell, was known for his ability to convey deep emotion through silent performance, which was crucial for the film's emotional core about aging and obsolescence.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Irving G. Ries emphasized the contrast between intimate family moments and spectacular fire sequences. The film used innovative camera techniques for its time, including mobile shots during action scenes and dramatic lighting effects to enhance the fire sequences. The visual style incorporated both the gritty realism of urban firefighting and the romanticized melodrama typical of silent era family dramas. The camera work during fire scenes was particularly notable for creating tension and spectacle without modern special effects technology.

Innovations

The film was notable for its relatively advanced special effects in depicting realistic fire scenes for the early 1920s. The production used innovative techniques involving controlled burns, smoke effects, and camera tricks to create convincing fire sequences without endangering the cast. The film also featured authentic fire department equipment of the era, providing historical documentation of the transition period between horse-drawn and motorized firefighting apparatus. The technical crew developed new methods for simulating building collapses and other fire-related disasters safely on set.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Third Alarm' would have been accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The original score was likely composed to enhance both the dramatic family scenes and the action sequences, with different musical themes for the various characters and situations. Theater orchestras would have used cue sheets provided by the studio to coordinate the music with the on-screen action. The music would have been particularly important during the fire scenes to build tension and excitement.

Famous Quotes

A man's not old until his heart forgets how to be brave.

The flames may be new, but courage is timeless.

Some things a machine can never replace - like a man's devotion.

Memorable Scenes

- The emotional retirement scene where Dan McDowell says goodbye to his horse Bullet

- The spectacular multi-alarm fire sequence with realistic rescue operations

- The courtroom scene where Dan is cleared of theft charges

- The climactic rescue of June Rutherford from the burning building

- The father-son reconciliation scene after the fire

Did You Know?

- Director Emory Johnson was a former actor who turned to directing and specialized in action and adventure films

- The film was part of a series of films Johnson made focusing on public service professionals like firefighters and police officers

- Real firefighters were used as extras in many scenes to ensure authenticity

- The horse Bullet was played by a trained animal actor who had appeared in several other films of the era

- The fire scenes were considered groundbreaking for their time, using innovative techniques to create realistic flames without endangering cast

- The film was released during a period when firefighting technology was rapidly changing from horse-drawn to motorized equipment

- Emory Johnson often cast his wife, Ella Hall, in his films, though she played a supporting role here

- The film's title 'The Third Alarm' refers to the highest level of fire emergency in the early 20th century fire department system

- This was one of the earliest films to address the theme of technological displacement of workers

- The film's success led to several other firefighter-themed movies throughout the 1920s

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews praised the film's realistic fire sequences and the emotional performance of Ralph Lewis as the aging firefighter. Critics noted the film's authentic depiction of fire department operations and its timely social commentary about technological change. However, some reviewers found the melodramatic elements somewhat predictable, even for the standards of silent cinema. Modern film historians recognize 'The Third Alarm' as an interesting example of early social problem cinema, though it's generally considered a minor work within Emory Johnson's filmography.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences of the era responded positively to the film's action sequences and emotional family drama. The movie particularly appealed to working-class viewers who could relate to themes of job insecurity and generational conflict. Firefighters and their families reportedly found the film especially moving and authentic. The combination of spectacular fire scenes and heartfelt family dynamics made it a popular choice at neighborhood theaters, though it didn't achieve the blockbuster status of some other silent films of the period.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards documented for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Great Fire (silent film tradition)

- Contemporary newspaper stories about firefighter heroes

- D.W. Griffith's melodramatic style

- Social problem films of the early 1920s

This Film Influenced

- Later firefighter films of the silent and early sound era

- Workplace dramas of the 1920s and 1930s

- Films addressing technological displacement

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is believed to be partially preserved with some reels surviving in film archives, though it may not be complete. As with many silent films from this period, some deterioration and loss of footage has likely occurred over time. The surviving elements are held by various film preservation institutions, though public access may be limited.