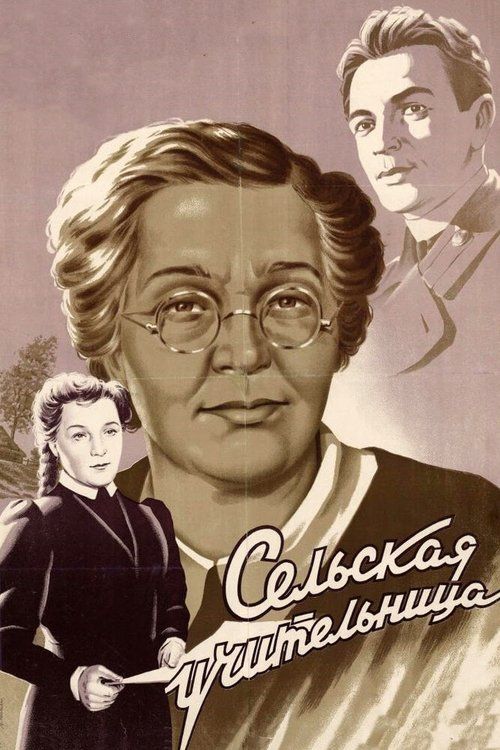

The Village Teacher

Plot

The film follows the life of Varvara Vasilievna Martynova, a young idealistic woman who leaves imperial St. Petersburg in the early 1900s to become a teacher in a remote Russian village. Inspired by the revolutionary 'People's Will' movement and driven by her desire to enlighten the peasantry, she faces numerous challenges including poverty, superstition, and resistance from conservative villagers. Through decades of service, she witnesses and participates in the transformation of Russian society from the final years of Tsarist rule through the 1917 Revolution, collectivization, World War II, and into the post-war Soviet era. The narrative spans nearly half a century, showing how one dedicated teacher's life becomes intertwined with the monumental changes sweeping through her country. Her personal sacrifices and unwavering commitment to education ultimately earn her the respect and love of generations of villagers who evolve from illiterate peasants to educated Soviet citizens.

About the Production

The film was shot in the immediate post-World War II period when Soviet cinema was rebuilding after massive destruction. Director Mark Donskoy faced significant challenges securing resources and film stock, which was still scarce after the war. The production team spent considerable time researching rural Russian life across different historical periods to ensure authenticity in costumes, sets, and social dynamics. The film employed hundreds of extras from local villages to create authentic crowd scenes depicting various historical moments.

Historical Background

The Village Teacher was produced in the immediate aftermath of World War II, during a period known as the Zhdanov Doctrine, when Soviet cultural policy demanded strict adherence to socialist realism. The film reflects the Soviet Union's massive post-war reconstruction efforts and the emphasis on rebuilding the educational system, which had suffered tremendously during the war. The movie's narrative of progress from Tsarist backwardness to Soviet enlightenment served as powerful propaganda for the communist vision of historical development. Released during the early Cold War, the film was also intended to showcase Soviet cultural achievements to both domestic and international audiences, demonstrating the supposed superiority of the Soviet system through the story of educational advancement.

Why This Film Matters

The Village Teacher became a cultural touchstone in Soviet society, establishing the archetype of the selfless, dedicated teacher as a heroic figure in socialist culture. The film influenced generations of Soviet educators, many of whom cited Varvara as their inspiration for entering the teaching profession. Its portrayal of rural transformation through education became part of the official narrative of Soviet progress and was frequently referenced in educational materials and teacher training programs. The movie's international success helped establish Soviet cinema as a force capable of producing works with both ideological content and artistic merit, challenging Western perceptions of Soviet cultural production as merely propagandistic.

Making Of

Mark Donskoy approached this project with meticulous attention to historical accuracy, consulting with historians and education specialists to recreate the evolving methods of rural teaching across different eras. Vera Maretskaya underwent extensive preparation, spending time in rural schools and studying the physical transformation of women who dedicated their lives to teaching. The production faced significant challenges in depicting the passage of time within a single narrative, using innovative makeup techniques and costume evolution to show aging. The film's battle scenes during the World War II sequence were particularly difficult to film, as the production had limited access to military equipment and had to creatively use whatever resources were available in the immediate post-war period. The relationship between Donskoy and Maretskaya was famously collaborative, with the actress contributing significantly to developing her character's psychological depth and emotional journey.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography, handled by Sergei Urusevsky, employed a visual style that evolved with the historical periods depicted, using warmer, more intimate lighting for the early Tsarist scenes and progressively brighter, more open compositions for the Soviet era. The camera work emphasized the contrast between the darkness of illiteracy and the light of knowledge, with recurring visual motifs of light through windows symbolizing enlightenment. Urusevsky used deep focus techniques to create rich compositions showing both the teacher and her students within their environment, reinforcing the film's themes of social transformation. The battle sequences during the World War II section utilized dynamic camera movement and montage techniques influenced by Soviet montage theory of the 1920s.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in Soviet cinema, particularly in its use of makeup and prosthetics to show realistic aging over a forty-year span. The production team developed new techniques for creating period-appropriate visual textures, from the rough-hewn village interiors of the early 1900s to the modernized Soviet school of the post-war era. The film's sound recording techniques were advanced for their time, particularly in capturing the natural sounds of rural environments and the changing acoustics of different historical periods. The battle sequences utilized innovative special effects techniques that maximized the impact of limited resources, creating convincing war scenes with minimal actual destruction.

Music

The musical score was composed by Lev Shvarts, who created a leitmotif-based soundtrack that evolved throughout the film to reflect the changing historical periods. The main theme, associated with Varvara's idealism, undergoes subtle transformations as the character ages and society changes. Folk melodies from various Russian regions were incorporated to emphasize the rural setting and the diversity of the population Varvara serves. The soundtrack prominently features choral arrangements that grow in complexity and grandeur as the film progresses, symbolizing the collective advancement of Soviet society. During the revolutionary sequences, Shvarts incorporated elements of revolutionary songs, while the wartime scenes used more somber, dramatic orchestration.

Famous Quotes

To teach is to light a candle in the darkness of ignorance - a light that will never be extinguished.

A single educated person is like a single soldier in battle, but together we become an army of enlightenment.

The revolution begins not with guns, but with books in the hands of children.

They call me crazy for leaving the city for this village, but I know that true civilization is built here, in the hearts of the simple people.

When you teach a child to read, you don't just give them letters - you give them the keys to the entire world.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where young Varvara arrives at the remote village, her modern city clothes contrasting sharply with the primitive rural setting, establishing the central conflict between enlightenment and tradition.

- The powerful scene where Varvara teaches her first class under a tree after the village school burns down, demonstrating her unwavering commitment despite setbacks.

- The emotionally charged sequence during the 1917 Revolution when former students return as soldiers, showing how education and political awakening are intertwined.

- The heartbreaking wartime scene where Varvara helps evacuate her students while bombs fall around them, symbolizing the defense of the future through education.

- The final scene showing the elderly Varvara watching her former students, now grown and successful, return to visit her, providing visual confirmation of her life's impact.

Did You Know?

- Vera Maretskaya's performance as Varvara earned her the Stalin Prize, one of the Soviet Union's highest artistic honors

- The film was one of the first major Soviet productions to address the role of teachers in building socialist society

- Director Mark Donskoy was known for his biographical films about Maxim Gorky before making this narrative feature

- The film's timeline spans approximately 40 years of Russian history, requiring the lead actress to portray her character from young adulthood to old age

- The movie was screened at the first Cannes Film Festival in 1946, representing Soviet cinema on the international stage

- The character of Varvara was partially inspired by real rural teachers who participated in the literacy campaigns of the 1920s and 1930s

- The film was used as an educational tool in Soviet teacher training institutions for decades

- Despite its ideological content, the film was praised internationally for its humanistic approach and technical excellence

- The production employed actual village school buildings rather than studio sets for many key scenes

- The film's success led to a trend of 'teacher films' in Soviet cinema throughout the late 1940s and 1950s

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film as a masterpiece of socialist realism, highlighting Vera Maretskaya's performance as embodying the ideal Soviet woman. Pravda and other official publications lauded the film's historical perspective and its demonstration of the communist party's role in advancing education. Western critics, while noting the film's ideological elements, were impressed by its technical quality and Maretskaya's powerful performance. The New York Times review acknowledged the film's propaganda elements but praised its 'sincerity and human warmth.' Modern film scholars re-examine the work as both a product of its time and a sophisticated piece of cinematic art that manages to transcend its ideological constraints through its focus on universal human experiences.

What Audiences Thought

The Village Teacher was enormously popular with Soviet audiences, becoming one of the highest-grossing films of 1947. Viewers connected emotionally with Varvara's struggles and triumphs, and many teachers wrote letters to Maretskaya expressing how the film reflected their own experiences. The film's success led to repeat screenings in theaters across the Soviet Union for several years. International audiences, particularly in Eastern Europe and parts of Asia where the film was distributed, responded positively to its humanistic elements despite its Soviet context. The movie developed a cult following among educators and remained a beloved classic throughout the Soviet period, with annual television broadcasts becoming a tradition in many households.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize (First Degree) for Mark Donskoy and Vera Maretskaya (1948)

- Best Actress Award at the Venice Film Festival for Vera Maretskaya (1947)

- Best Director Award at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival for Mark Donskoy (1948)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet montage theory

- Socialist realist aesthetic

- Maxim Gorky's literary works about rural Russia

- Vladimir Lenin's writings on education

- Stanislavski's acting system

- Earlier Soviet biographical films about educators

This Film Influenced

- Spring on Zarechnaya Street (1956)

- The Chairman (1964)

- Commissar (1967)

- The Beginning (1970)

- Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (1980)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia (State Film Archive) and has undergone digital restoration as part of Soviet cinema heritage projects. Original nitrate elements were successfully transferred to safety film in the 1970s. A high-definition digital restoration was completed in 2018 as part of a comprehensive Soviet classic cinema preservation initiative. The restored version has been screened at international film festivals and is considered to be in excellent preservation condition.