The Wind

"Nature's most terrifying force... The Wind!"

Plot

Letty Mason travels from Virginia to live with her cousin Beverly and his wife Cora on their isolated West Texas ranch, immediately finding herself overwhelmed by the relentless, howling wind and endless sand. The harsh environment is matched by Cora's cold reception, as she views Letty as competition for male attention in the barren landscape. Three men pursue Letty: the local cattle dealer Roddy, the handsome but philandering Wirt, and the quiet, dependable Lige Hightower. After a traumatic encounter with Wirt, Letty marries Lige but remains haunted by her experiences and the oppressive wind that seems to embody her psychological torment. In the film's climax, Letty finally confronts both her inner demons and the elemental forces that have plagued her, achieving a hard-won peace in the unforgiving desert landscape.

About the Production

The film faced significant production challenges, particularly in creating realistic wind effects. The production used airplane propellers and wind machines to generate the constant gale conditions, sometimes at speeds of 60-70 mph. The sand used in filming was actually fine sawdust mixed with sand to prevent it from being too harsh on the actors. Lillian Gish reportedly suffered from eye irritation and respiratory issues during the extensive wind scenes. The original ending was much darker, with Letty wandering into the desert to die, but test audiences demanded a more hopeful conclusion, leading to reshoots.

Historical Background

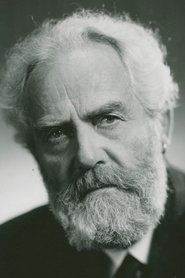

The Wind was produced during the tumultuous transition from silent films to talkies in 1928, a period of enormous technological and artistic upheaval in Hollywood. The silent era was reaching its zenith of artistic sophistication, with directors like Sjöström pushing the boundaries of visual storytelling. This film represents the culmination of silent cinema's artistic achievements even as the industry was being revolutionized by sound. The late 1920s also saw America grappling with modernization versus traditional values, themes reflected in the film's conflict between civilization and the harsh frontier. The psychological realism and intense focus on character psychology that Sjöström brought to the film was part of a broader movement toward more sophisticated narratives in late silent cinema. Additionally, the film's portrayal of environmental struggle resonated with Dust Bowl experiences that would soon devastate the American West, though the film predates that ecological disaster.

Why This Film Matters

'The Wind' stands as one of the masterpieces of late silent cinema and a landmark in environmental filmmaking. It represents one of the first films to use natural elements as a psychological force, with the wind functioning as both literal weather and metaphor for psychological turmoil. The film's intense focus on female psychology and isolation in a hostile environment was groundbreaking for its time. Lillian Gish's performance became a touchstone for naturalistic acting in silent film, demonstrating how emotion could be conveyed through subtle physical expression rather than theatrical gestures. The film has been cited as a major influence on later psychological thrillers and environmental dramas. Its restoration and preservation have made it a crucial document of silent cinema's artistic achievements, and it's frequently studied in film courses as an example of how visual storytelling can create psychological depth without dialogue. The film also represents a unique collaboration between Swedish and American cinema sensibilities, bringing European artistic sophistication to the American Western genre.

Making Of

The production of 'The Wind' was marked by extraordinary physical challenges for the cast and crew. Director Victor Sjöström, known in Sweden as 'The Victor Seastrom,' was a master of visual storytelling and insisted on authentic, visceral wind effects. The production team constructed massive wind machines using airplane propellers, creating winds so powerful that they sometimes damaged the set and endangered the performers. Lillian Gish, dedicated to her craft, performed many of her own stunts, including scenes where she was battered by sand and wind. The relationship between Gish and Sjöström was one of mutual artistic respect; both were at the height of their creative powers. The film's ending controversy became legendary - after preview audiences reacted negatively to the original bleak ending where Letty perishes in the desert, MGM forced reshoots to create a more hopeful conclusion, much to Sjöström's dismay. The production also pioneered innovative techniques for simulating sandstorms and wind effects that would influence later desert films.

Visual Style

The cinematography by John Arnold was revolutionary for its time, particularly in its handling of wind and sand effects. Arnold employed innovative techniques including multiple exposures to create the illusion of endless sand, and carefully calibrated lighting to suggest the harsh, unforgiving sun of West Texas. The camera work emphasizes isolation and vulnerability through wide shots that dwarf characters against the vast landscape, and claustrophobic close-ups that capture Letty's psychological torment. The film's visual language uses the wind as an active character, with camera movements that suggest being buffeted by gales. Arnold pioneered techniques for filming in artificial wind conditions, including special filters to protect the lens and modified camera housings. The cinematography creates a dreamlike, nightmarish quality that blurs the line between psychological and environmental horror, influencing countless later films that use weather as psychological metaphor.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its groundbreaking creation of realistic wind and sandstorm effects. The production team, led by special effects expert A. Arnold Gillespie, designed and built massive wind machines using aircraft propellers capable of producing winds up to 70 miles per hour. They developed a special mixture of fine sawdust and sand that would look authentic on camera while being less harmful to performers than pure sand. The film also pioneered techniques for filming in extreme weather conditions, including specially modified camera equipment and innovative lighting setups that could withstand the wind. The production's ability to maintain visual continuity during scenes with flying debris and artificial weather was remarkable for the era. Additionally, the film's seamless blending of location shooting in the Mojave Desert with studio work demonstrated sophisticated matte painting and composite techniques that were ahead of their time.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Wind' originally had no recorded soundtrack but was accompanied by live musical performances during theatrical screenings. The original score was composed by William Axt and performed by theater orchestras, with music that emphasized the wind's relentless presence through sustained strings and percussion elements. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores, most notably a 2008 version by Stephen Horne and a 2015 score by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra. These modern interpretations attempt to capture the psychological intensity of the original while using contemporary musical language. The film's effective use of silence as a dramatic element, particularly in moments when the wind briefly subsides, demonstrates sophisticated understanding of audio-visual relationships despite the lack of recorded sound.

Famous Quotes

The wind! It won't let me alone! It's trying to drive me mad!

I'm afraid of the wind. It's always there, watching, waiting.

Out here, a woman needs a man to protect her from everything - even herself.

The wind knows all our secrets and whispers them to the sand.

In this country, the wind is the only thing that's really alive.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Letty first arrives in West Texas and is immediately overwhelmed by the relentless wind and sand, establishing the film's central antagonist

- The sandstorm sequence where Letty battles both the physical storm and her psychological breakdown, considered one of the most intense scenes in silent cinema

- The wedding scene where the wind literally tears at Letty's veil and dress, symbolizing nature's resistance to human attempts at order and civilization

- The final scene where Letty achieves peace by accepting rather than fighting the wind, showing her transformation from victim to survivor

- The scene where Letty confronts Wirt in the isolated cabin, a masterclass in building tension through visual storytelling rather than dialogue

Did You Know?

- This was Lillian Gish's last silent film and one of her most acclaimed performances, which she considered among her best work

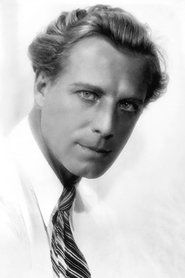

- The wind effects were so intense that Lars Hanson (Lige) was reportedly blown off his feet multiple times during filming

- Director Victor Sjöström was already a legendary Swedish director before coming to Hollywood, and this was his final American film

- The film was based on a novel of the same name by Dorothy Scarborough, who was inspired by her experiences growing up in West Texas

- MGM originally wanted to add sound effects and dialogue to capitalize on the new talkie craze, but Victor Sjöström fought to keep it silent

- The production used over 40 tons of sand/sawdust mixture during filming

- Gish's contract with MGM gave her script approval and the right to choose her director, which is how Sjöström was hired

- The film was considered too bleak and disturbing by many contemporary audiences, contributing to its poor box office performance

- Montagu Love, who played the villainous Wirt, was actually British and had to master an American accent for the role

- The wind machines used were so powerful that they could blow a man off his feet at full speed

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed to positive, with many critics praising Lillian Gish's performance as extraordinary and Victor Sjöström's direction as masterful, though some found the film's bleakness overwhelming. The New York Times hailed it as 'a remarkable achievement in cinematic art' while Variety noted its 'unrelenting intensity.' Modern critics have been overwhelmingly positive, with the film now regarded as one of the greatest silent films ever made. Critics particularly praise its sophisticated use of visual metaphor, psychological depth, and Gish's nuanced performance. The film holds a 92% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on critical reviews, with many calling it 'a haunting masterpiece' and 'one of the last great works of the silent era.' Film scholars have written extensively about its innovative techniques and its status as a bridge between Victorian melodrama and modern psychological cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in 1928 was poor, with many viewers finding the film too bleak and disturbing for entertainment. The relentless wind and psychological intensity proved overwhelming for audiences seeking escapism during the Great Depression's onset. Test screenings led to the controversial changing of the ending from tragic to hopeful, as audiences rejected the original conclusion. However, modern audiences rediscovering the film through revivals and home video have responded much more positively, with many considering it a powerful and haunting work of art. Contemporary viewers often express surprise at the film's sophistication and emotional power, particularly given its silent format. The film has developed a cult following among silent film enthusiasts and is frequently cited as an entry point for people interested in exploring silent cinema beyond the most famous comedies.

Awards & Recognition

- None - The film was released before the Academy Awards were established for acting categories, and it did not receive any major awards at the time

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) - for its visual poetry and emotional intensity

- The General (1926) - for its technical innovation and action sequences

- Swedish silent films of Sjöström's earlier career - particularly 'The Outlaw' and 'The Phantom Chariot' for their supernatural elements and psychological depth

- German Expressionist cinema - for its use of environment to reflect psychological states

- Western genre conventions - which the film subverted through its psychological focus

This Film Influenced

- Days of Heaven (1978) - for its poetic use of landscape and wind

- The Thin Red Line (1998) - for its philosophical approach to nature and human conflict

- The New World (2005) - for its portrayal of environmental challenge and psychological adaptation

- The Revenant (2015) - for its visceral portrayal of survival against natural elements

- Woman Walks Ahead (2017) - for its focus on female experience in the American West

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for decades but a complete print was discovered in the MGM vaults in the 1960s. The original negative had deteriorated significantly, but a 35mm print was used for restoration. In 2012, The Criterion Collection released a digitally restored version based on the best surviving elements. The restoration involved extensive digital cleanup to repair damage from the original nitrate decomposition. The film is now preserved in the MGM/UA film collection and at the Library of Congress. The restored version runs 71 minutes, slightly shorter than the original 75-minute cut, with the missing footage believed to be permanently lost. The film is considered to be in good preservation status with high-quality viewing options available through various home media formats.