The Wizard of Oz

"A Royal Romp in the Realm of Fantasy!"

Plot

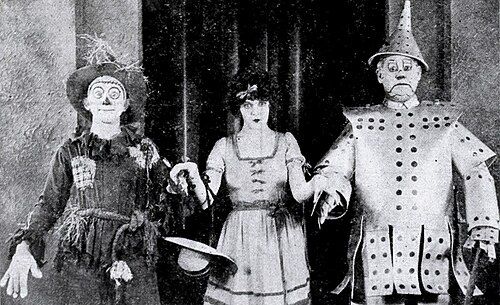

In this 1925 silent adaptation, Dorothy (Dorothy Dwan) is a farm girl who discovers she is actually Princess Dorothea of Oz, the rightful heir to the throne. When a tornado strikes, Dorothy, her farmhands, and Uncle Henry are swept away to the magical land of Oz. Once there, the farmhands transform into familiar characters: the Scarecrow (Larry Semon), the Tin Woodsman (Oliver Hardy), and the Cowardly Lion (Spencer Bell). The group must help Dorothy reclaim her throne from the evil Prime Minister Kruel, who has usurped power with the help of his wicked ally Lady Vishuss. The film culminates in a series of comedic chase sequences and battles as Dorothy fights to restore order to Oz and claim her royal destiny.

About the Production

This was Larry Semon's most expensive and ambitious production, featuring elaborate sets and costumes. The film was shot during the summer of 1925 with extensive special effects for the tornado sequence. Semon took significant creative liberties with L. Frank Baum's original story, essentially rewriting it to showcase his physical comedy style. The production faced financial difficulties during filming, with Semon personally investing much of his own money. The elaborate Oz sets were some of the most expensive constructed for a comedy film of that era.

Historical Background

The Wizard of Oz (1925) emerged during the golden age of silent cinema, when fantasy films were gaining popularity but still considered risky investments. The mid-1920s saw Hollywood studios experimenting with increasingly elaborate productions as they competed for audiences. This period also marked the peak of the silent comedy star system, with performers like Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Charlie Chaplin at their height. Larry Semon was a major comedy star at this time, known for his elaborate visual gags and physical comedy. The film's production coincided with the transition toward bigger-budget features in Hollywood, as studios moved away from short films. The 1920s also saw growing interest in adapting literary works for the screen, though adaptations often took significant liberties with source material. This version of Oz reflects the era's appetite for spectacle and the belief that comedy could be successfully blended with fantasy elements.

Why This Film Matters

While largely overshadowed by the 1939 MGM version, the 1925 Wizard of Oz represents an important chapter in the history of Oz adaptations and silent fantasy cinema. It demonstrates how literary properties were often completely reimagined for different audiences and eras. The film serves as a time capsule of 1920s comedy sensibilities and visual storytelling techniques. Its commercial failure is often cited as an example of the risks involved in big-budget fantasy productions during the silent era. The film's rediscovery has made it valuable for film historians studying the evolution of fantasy cinema and the adaptation process. It also provides insight into Larry Semon's career and the broader landscape of silent comedy. The casting of Oliver Hardy before his Laurel and Hardy fame makes it historically significant for comedy enthusiasts. The film's treatment of racial stereotypes, particularly in the casting of Spencer Bell as the Lion, reflects the problematic attitudes of the era and serves as an important historical document of Hollywood's racial practices.

Making Of

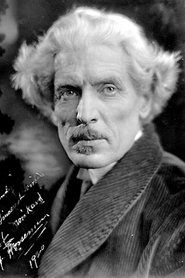

The making of this 1925 Wizard of Oz was marked by ambition and excess. Larry Semon, at the height of his silent comedy fame, poured his resources into what he hoped would be his masterpiece. He completely reimagined Baum's story, inserting himself as the central comedic figure and making Dorothy a princess with a royal backstory. The production featured some of the most elaborate sets of the silent era, including a massive Emerald City constructed on the Chadwick Studios backlot. Semon's wife Dorothy Dwan was cast as the lead, despite limited acting experience. The film's physical comedy sequences were dangerous and demanding, with Semon performing many of his own stunts. Financial troubles plagued the production from the start, with Semon taking out loans and mortgaging his home to complete filming. The post-production process was rushed to meet the September release date, resulting in editing problems that affected the film's coherence.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Hans F. Koenekamp employed the techniques and visual language of mid-1920s silent cinema. The film features elaborate camera movements for its time, including tracking shots during the chase sequences. The tornado scene utilized innovative special effects photography, including double exposure and miniatures. The Oz sequences used tinting and toning techniques to create magical atmospheres, with the Emerald City scenes featuring distinctive green hues. Koenekamp employed wide shots to showcase the impressive sets while maintaining clear sightlines for the physical comedy. The Kansas scenes were shot in a more straightforward style, contrasting with the fantastical visual treatment of Oz. The film's visual style reflects the transition from the simpler compositions of early silent films to the more sophisticated cinematography that would characterize the late 1920s.

Innovations

The film showcased several technical innovations for its time, particularly in its special effects sequences. The tornado scene was particularly ambitious, utilizing a combination of wind machines, rotating sets, and matte paintings to create the illusion of a massive storm. The transformation sequences, where farm characters become their Oz counterparts, used innovative editing techniques and makeup effects. The Emerald City set featured some of the most elaborate miniatures and forced perspective photography of the silent era. The film also employed early green screen techniques (using black screens and double exposure) for certain magical effects. The costume design for the fantasy characters was technically sophisticated, with the Tin Woodsman costume requiring complex construction to allow for Oliver Hardy's physical comedy. While not groundbreaking in terms of new technology, the film pushed existing techniques to their limits in service of its fantasy elements.

Music

As a silent film, The Wizard of Oz (1925) had no synchronized soundtrack but would have been accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The original cue sheets suggested classical pieces and popular songs of the era to accompany different scenes. For the Kansas sequences, pastoral American music was recommended, while the Oz sequences called for more fantastical and dramatic compositions. Modern restorations have been scored by various composers, including silent film specialist Robert Israel. The 2012 restoration featured a new orchestral score by Rodney Sauer that attempted to capture both the comedic and fantasy elements of the film. The original theatrical experience would have varied significantly from theater to theater, depending on the house organist or orchestra's interpretation of the suggested musical cues.

Famous Quotes

Dorothy: 'I'm not a princess! I'm just a simple farm girl!'

Prime Minister Kruel: 'The throne belongs to me now!'

Scarecrow: 'If I only had a brain... and some straw!'

Tin Woodsman: 'My heart may be tin, but it feels heavy with sorrow'

Uncle Henry: 'There's no place like home, even if it's just a farm'

Memorable Scenes

- The spectacular tornado sequence that sweeps Dorothy and her companions to Oz, featuring innovative special effects and dramatic editing

- The transformation scene where the farmhands magically become their Oz counterparts, showcasing 1920s makeup and costume effects

- The elaborate chase through the Emerald City, combining Semon's signature physical comedy with fantasy elements

- The final coronation scene where Dorothy claims her throne, featuring impressive set design and crowd scenes

- The comedic introduction of the Tin Woodsman, with Oliver Hardy's physical gags in the cumbersome metal costume

Did You Know?

- This film was considered lost for decades until a complete print was discovered in the 1970s

- Oliver Hardy, later famous as half of Laurel and Hardy, plays the Tin Woodsman

- Larry Semon not only directed but also starred as the Scarecrow and co-wrote the screenplay

- The film deviates so significantly from Baum's book that Baum's estate unsuccessfully sued for copyright infringement

- Dorothy Dwan, who played Dorothy, was Larry Semon's wife in real life

- This was the first feature-length adaptation of The Wizard of Oz (though there were earlier shorts)

- The film's failure contributed to Larry Semon's decline in Hollywood and his early death in 1928

- Spencer Bell, an African American actor, played the Cowardly Lion but was billed as G. Howe Black

- The tornado effect was created using wind machines and spinning sets, impressive for 1925

- Unlike the 1939 version, this film begins in Kansas but the farm characters don't dream - they actually go to Oz

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1925 were largely unimpressed with the film, with many reviews criticizing its departure from Baum's beloved story. Variety noted that 'Semon has taken liberties with the original that will disappoint Oz fans' while acknowledging the film's visual spectacle. The New York Times called it 'a disjointed affair that sacrifices story for comedy.' Modern critics have been more charitable, viewing it as a fascinating artifact of silent cinema. The film is now appreciated for its historical value and as an example of early fantasy filmmaking, though most agree it's not Semon's best work. Film historians often point to it as an interesting failed experiment in combining comedy with fantasy elements. The rediscovery and restoration of the film has led to reevaluation, with some critics finding charm in its silent-era aesthetics and physical comedy.

What Audiences Thought

The 1925 Wizard of Oz was a box office disaster upon its initial release, disappointing both Oz fans and Semon's comedy audience. Many viewers were confused and upset by the radical changes to the familiar story, while Semon's regular fans found the fantasy elements detracted from his usual comedy style. The film performed poorly across the country, with many theaters pulling it early due to low attendance. Audience feedback cards from the era show viewers complaining about the confusing plot and excessive focus on Semon's character at the expense of Dorothy's story. Modern audiences viewing the film at revival screenings and film festivals tend to approach it with more curiosity and historical perspective, often finding it entertaining as a silent comedy despite its narrative flaws. The film has developed a cult following among Oz enthusiasts and silent film fans who appreciate its unique place in cinema history.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- L. Frank Baum's 'The Wonderful Wizard of Oz' book

- Other 1920s fantasy films

- Larry Semon's previous comedy shorts

- Contemporary stage adaptations of Oz

- Silent era slapstick comedy traditions

This Film Influenced

- The Wizard of Oz (1939)

- Journey Back to Oz (1972)

- Return to Oz (1985)

- Various Oz television adaptations

- Oz the Great and Powerful (2013)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for many years until a complete 35mm print was discovered in the 1970s. The Library of Congress holds a preserved copy, and the film has undergone digital restoration. Some versions circulating are incomplete or in poor condition, but a quality restoration exists. The film is now in the public domain and has been released on DVD and Blu-ray by various specialty labels. The restoration work has stabilized the surviving elements and recreated missing title cards where necessary.