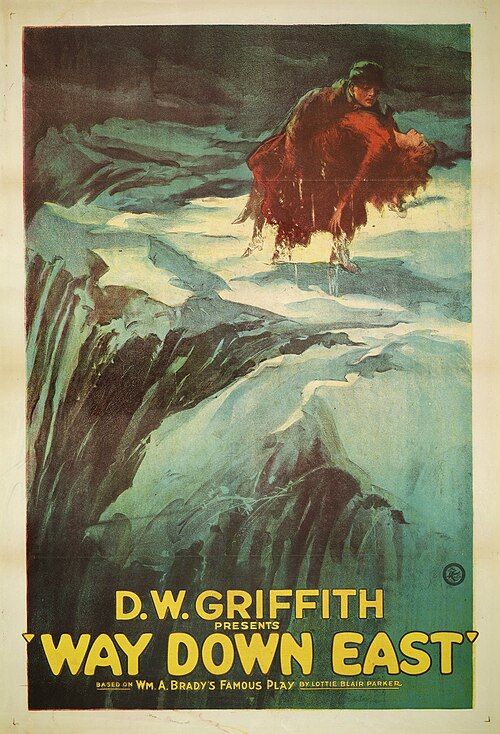

Way Down East

"The story of a woman who paid for the sins of the world."

Plot

Anna Moore, a naive country girl, travels to Boston to visit wealthy relatives and meets the charming but deceitful Lennox Sanderson, who tricks her into a sham marriage and seduces her. When Anna becomes pregnant, Sanderson abandons her, and after her baby dies, she finds herself ostracized by society for bearing a child out of wedlock. Destitute and alone, Anna eventually finds refuge with the Bartlett family in rural New England, where she falls in love with their gentle son David, but her past threatens to destroy her newfound happiness when Sanderson reappears in her life. The film culminates in the legendary ice floe sequence where Anna, having fainted on a frozen river, is carried downstream on breaking ice toward a waterfall while David desperately races to save her.

About the Production

The film required six months of difficult production, with the famous ice floe sequence filmed in real sub-zero temperatures. Griffith spent $50,000 creating artificial snow and insisted on authentic winter conditions. Lillian Gish performed her own dangerous stunts in the ice sequence, resulting in permanent hand damage from gripping ice. The production was so extensive that it required multiple camera units and innovative special effects techniques for the river sequences.

Historical Background

Way Down East was released during a period of profound social transformation in America, coinciding with the ratification of the 19th Amendment granting women's suffrage and changing attitudes toward female sexuality and morality. The film emerged at the height of D.W. Griffith's career, following the controversy of The Birth of a Nation and the artistic ambition of Intolerance, representing his attempt to create socially relevant dramas that addressed contemporary moral issues. The early 1920s marked the transition of the film industry from short films to feature-length productions, with budgets and technical capabilities expanding rapidly. The film's treatment of a 'fallen woman' reflected ongoing debates about sexual double standards and the role of women in society, while its commercial success demonstrated the growing cultural power of cinema as a medium for addressing social issues.

Why This Film Matters

Way Down East became one of the most influential melodramas of the silent era, establishing conventions that would persist for decades in cinema. Its treatment of themes of female virtue, social hypocrisy, and redemption resonated deeply with contemporary audiences and helped shape the development of the melodrama genre. The film's iconic ice floe sequence became one of the most referenced and imitated scenes in cinema history, influencing countless later films and establishing a template for dramatic natural disaster sequences. The commercial success of the film demonstrated the viability of feature-length melodramas and helped establish United Artists as a major force in the industry. It also cemented Lillian Gish's status as one of cinema's first great dramatic actresses, proving that female-led films could achieve massive commercial success.

Making Of

The production was marked by Griffith's obsessive perfectionism and willingness to risk his actors' safety for authenticity. The ice floe sequence required weeks of preparation in harsh winter conditions, with the crew working in temperatures well below zero. Gish, dedicated to Griffith's vision, performed all her own stunts despite the dangerous conditions, including being dragged through freezing water and floating on actual ice floes. The production used a combination of real location shooting and elaborate studio sets, with Griffith pioneering new techniques for creating realistic snow and ice effects. The film's extended location shooting in rural New England was highly unusual for the period, when most productions were studio-bound. Griffith's insistence on emotional authenticity led to multiple reshoots of key scenes, particularly the dramatic finale, with the director pushing his actors to their physical and emotional limits.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Billy Bitzer and Hendrik Sartov was groundbreaking for its time, particularly in the outdoor sequences and the innovative ice floe sequence. The winter scenes used natural lighting to create stark, beautiful imagery that emphasized the harshness of Anna's situation while simultaneously creating a sense of visual poetry. The ice floe sequence employed revolutionary camera techniques, including moving shots that followed Gish across the ice and innovative angles that heightened the sense of danger. The contrast between the warm, intimate interior scenes and the cold, expansive exterior shots created a powerful visual narrative that perfectly complemented the story's emotional arc. The film's visual style influenced countless later productions and established new standards for location cinematography.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would influence cinema for decades. The ice floe sequence required complex engineering to create realistic ice flows while ensuring actor safety, including the construction of special tanks and mechanisms for controlling the ice movement. The production developed new techniques for filming in extreme weather conditions, including special camera housing and insulation methods to protect equipment. The film's length (145 minutes) was unusual for the period and required innovations in film distribution and projection to accommodate the extended running time. The production also experimented with early forms of process photography for certain scenes and developed new techniques for creating realistic snow and ice effects that would become standard practice in the industry.

Music

The original musical score was composed by Louis F. Gottschalk and performed by orchestras in theaters during screenings, with different theaters sometimes using variations of the score. Gottschalk's composition emphasized the emotional content of each scene, with dramatic themes for the ice floe sequence, romantic motifs for Anna and David's relationship, and somber passages for moments of tragedy. The score was designed to enhance the film's emotional impact without overwhelming the visual storytelling. Modern restorations have used newly composed scores that attempt to capture the spirit of the original while utilizing contemporary musical sensibilities. The importance of music to the film's effectiveness was widely recognized at the time, with reviews often praising the musical accompaniment as integral to the viewing experience.

Famous Quotes

I'm afraid I'm not very strong... but I'll try to be brave.

God forgive me for what I'm about to do.

There's a place for everyone in this world, if they'll only find it.

The past is dead, and we must live for the future.

I'm not afraid of anything now that I know you love me.

A woman's virtue is the most precious thing she possesses.

In God's eyes, the sinner who repents is greater than the righteous who never sinned.

Memorable Scenes

- The legendary ice floe sequence where Anna, having fainted on the frozen river, is carried downstream on breaking ice floes while David races across the landscape and along the riverbank to save her, culminating in her dramatic rescue from the waterfall's edge as the ice breaks apart beneath her

- The fake marriage scene where Sanderson tricks Anna with a mock ceremony in a beautiful garden, using romantic language to deceive the innocent country girl

- Anna's emotional breakdown upon learning of her baby's death, a scene of raw emotional power that showcases Gish's acting prowess

- The confrontation scene where Anna's past is revealed to the Bartlett family, creating tension and testing their Christian values of forgiveness

- The final reconciliation scene where David chooses Anna despite her past, affirming the film's themes of redemption and true love

- Anna's arrival at the Bartlett farm, contrasting the warmth and acceptance of rural life with the cold judgment of urban society

Did You Know?

- The ice floe sequence is considered one of the most dangerous stunt sequences ever filmed in silent cinema, with Lillian Gish performing in actual freezing water

- Gish's hand was permanently damaged during the ice floe filming when she gripped the ice for hours in sub-zero temperatures

- The film's massive success saved United Artists from financial collapse and established it as a major studio

- D.W. Griffith spent $50,000 just to create artificial snow, an unprecedented amount for special effects at the time

- The original stage play had been running for nearly 20 years before Griffith decided to adapt it for film

- The film was so long that it was originally released with an intermission, which was unusual for the period

- Audiences at initial screenings reportedly fainted during the ice floe sequence due to its intensity

- The film used over 7,000 feet of film just for the ice floe sequence alone

- Griffith built a special tank on location to film the water scenes, requiring complex engineering

- The movie's success allowed Griffith to build his own studio, Mamaroneck Studios, in New York

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics overwhelmingly praised the film's emotional power and technical achievements. The New York Times hailed it as 'a masterpiece of emotional storytelling,' while Variety noted its 'unprecedented technical brilliance' and predicted it would 'stand as one of the greatest achievements in motion picture art.' Modern critics recognize the film as a classic of silent cinema, with the ice floe sequence frequently cited as one of the greatest sequences in silent film history. While some contemporary reviewers note the film's Victorian moralism as dated, most acknowledge its artistic merit and historical importance. The film is generally regarded as one of Griffith's finest achievements after Intolerance, representing his ability to combine technical innovation with emotional storytelling.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a phenomenal commercial success, playing to sold-out theaters for months across the United States and internationally. Audiences were particularly moved by Lillian Gish's nuanced performance and the spectacular ice floe sequence, which reportedly caused viewers to faint in theaters during initial screenings due to its intensity. The film's themes of redemption and forgiveness resonated strongly with contemporary audiences, and word-of-mouth about the dramatic finale helped sustain ticket sales long after the film's initial release. The movie became one of the highest-grossing films of 1920, with repeat business being unusually high as audiences returned to experience the emotional impact of the story multiple times.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Medal of Honor (1920)

- National Board of Review Award for Best Film (1920)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Birth of a Nation (1915) - Griffith's earlier epic influenced the scale and narrative ambition

- Intolerance (1916) - Griffith's technical innovations and complex narrative structure carried over

- Victorian melodramas and 'fallen woman' stories from 19th-century literature

- The original stage play by William Brady, which had been a theatrical success for nearly 20 years

- Contemporary social reform movements addressing women's rights and sexual morality

This Film Influenced

- The Wind (1928) - Another Lillian Gish film featuring nature as antagonist

- Stella Dallas (1925, 1937) - Similar themes of maternal sacrifice and social ostracism

- The River (1929) - Used similar natural disaster sequences for dramatic effect

- The Grapes of Wrath (1940) - Rural family values versus social injustice

- A Place in the Sun (1951) - Similar themes of class differences and tragic romance

- The Sound of Music (1965) - Similar rural/urban contrast and themes of redemption

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in various archives including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. Multiple versions exist, with some scenes missing or damaged due to nitrate film deterioration over time. The most complete restoration was undertaken by the Museum of Modern Art in the 1990s, combining elements from various international prints to create the most complete version available. While not considered a lost film, some original footage may be missing, particularly from transitional scenes. The restoration work has been ongoing, with new digital restorations attempting to preserve and enhance the surviving footage for modern audiences.