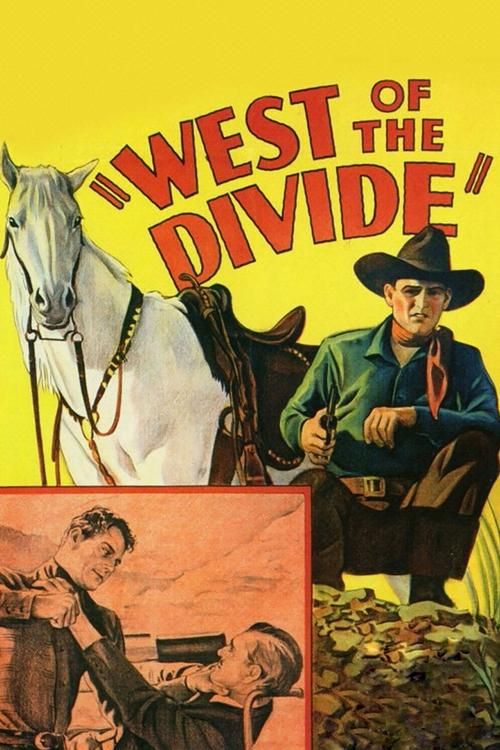

West of the Divide

"A Thrilling Western of Revenge and Romance!"

Plot

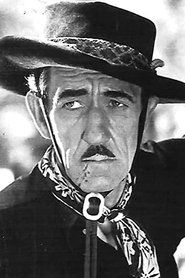

Ted Hayden arrives in a small western town seeking revenge for his father's murder. He discovers that a man named Gentry is leading a gang of cattle rustlers and decides to infiltrate the group by impersonating a wanted criminal named Gat Ganns. As Ted works his way into Gentry's trust, he learns that Gentry was actually responsible for killing his father years earlier. Along the way, Ted falls for Fay Winters, the sister of one of Gentry's men, and must navigate dangerous situations while maintaining his cover. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation where Ted reveals his true identity and brings the gang to justice.

About the Production

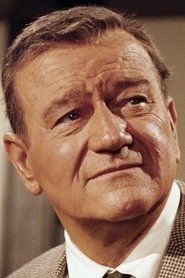

This was one of sixteen films John Wayne made for Lone Star Productions between 1933-1935. The film was shot in just six days, typical for the rapid production schedule of B-westerns. The Alabama Hills location was frequently used for westerns due to its dramatic rock formations that resembled the American West. George 'Gabby' Hayes was still developing his famous 'Gabby' persona and wasn't yet using that nickname in billing.

Historical Background

West of the Divide was released during the height of the Great Depression, when audiences sought escapist entertainment. 1934 was also the year the Hays Code began to be strictly enforced, though westerns were generally considered safe from censorship concerns. The film represents the transition from silent to sound westerns, with dialogue and sound effects becoming increasingly important. John Wayne was still a relatively unknown actor at this time, having not yet achieved stardom in Stagecoach (1939). The western genre was extremely popular in the 1930s, with hundreds of B-westerns produced annually to satisfy the demand of Saturday matinee audiences.

Why This Film Matters

While not considered a major work in John Wayne's filmography, West of the Divide represents an important step in his development as a western star. The film showcases early elements of the Wayne persona that would later become iconic: the stoic hero seeking justice, the moral certainty, and the physical presence. The film also demonstrates the formulaic nature of B-westerns that would dominate Saturday matinees for decades. Its public domain status has made it widely accessible, contributing to the preservation and study of 1930s western cinema. The film is part of the foundation upon which the myth of the American West was built in popular culture.

Making Of

The production was typical of the fast-paced B-western factory system of the 1930s. Director Robert N. Bradbury was known for his efficiency and could complete filming in under a week. John Wayne was still developing his screen persona and was paid only $2,500 per film during this period. The cast and crew often worked 12-14 hour days to meet the tight production schedules. Virginia Brown Faire, a former WAMPAS Baby Star, was nearing the end of her career and this role represented one of her last significant parts. The film's minimal sets were reused from other Lone Star productions to save costs, a common practice in low-budget western production.

Visual Style

The cinematography was handled by Archie Stout, who would later work with John Wayne on Stagecoach and become John Ford's regular cinematographer. The film utilizes natural lighting for outdoor scenes, typical of low-budget productions. The Alabama Hills locations provided dramatic backdrops that enhanced the visual scope despite the limited budget. Camera work was functional rather than innovative, focusing on clear storytelling and action visibility. The black and white photography emphasizes the stark contrasts of the western landscape.

Innovations

As a low-budget B-western, the film did not feature significant technical innovations. However, it represents the refinement of sound recording techniques for outdoor locations, which was still challenging in 1934. The film's efficient production methods and quick turnaround time demonstrated the industrialization of Hollywood filmmaking. The use of natural locations rather than studio sets helped establish the visual language of western cinema.

Music

The film featured a typical musical score for a 1934 western, with stock music tracks used throughout. No original songs were composed specifically for the film. The sound design emphasized gunshots, horse hooves, and ambient western sounds. Dialogue recording was primitive by modern standards, with the characteristic flat sound quality of early sound films. The musical cues followed the dramatic conventions of the era, with tense music for action scenes and romantic themes for love scenes.

Famous Quotes

I'm looking for a man named Gentry. He killed my father.

You can't run from the law forever, Gentry.

Sometimes a man has to do what's right, even if it's dangerous.

This town needs someone who isn't afraid to stand up to troublemakers.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Ted Hayden arrives in town and learns about Gentry's gang

- The confrontation where Ted reveals his true identity to Gentry

- The final shootout between Ted and the gang members

- The scene where Ted first meets Fay Winters and romantic tension is established

Did You Know?

- This was the first of three films that John Wayne and director Robert N. Bradbury made together in 1934

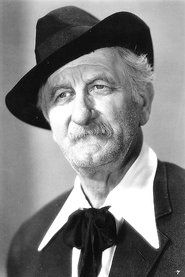

- George 'Gabby' Hayes appears clean-shaven in this film, before adopting his famous whiskered 'Gabby' character

- The film was originally titled 'The Man from Hell River' before being changed to 'West of the Divide'

- Virginia Brown Faire was a former silent film star making one of her last film appearances

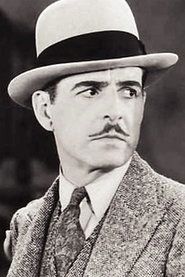

- The character name 'Gat Ganns' that Wayne impersonates was likely a play on 'gat' (slang for gun) and 'gann' (to devour)

- This film was part of a package of eight Wayne westerns sold to television in the 1950s that helped establish his TV stardom

- The film's copyright was not renewed and entered the public domain in 1962

- Robert N. Bradbury was the father of Bob Steele, another popular western star of the era

- The film features an early example of the 'undercover hero' trope that would become common in westerns

- John Wayne performed his own stunts in the film, including horse falls and fight sequences

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews were minimal, as B-westerns rarely received serious critical attention. The film was generally considered competent entertainment for its target audience of western fans. Modern critics view the film primarily as a historical artifact and early example of John Wayne's work. It's often cited as a representative example of the Lone Star Productions formula and the rapid-fire production methods of 1930s B-movies. Film historians note its importance in Wayne's career development rather than its artistic merits.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by its target audience of Saturday matinee western enthusiasts. John Wayne's growing popularity among western fans helped ensure the film's commercial success. The film's straightforward revenge plot and action sequences satisfied the expectations of 1930s western audiences. In later years, the film found new audiences through television broadcasts and home video, particularly among John Wayne completists and classic western enthusiasts.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The traditional revenge western formula

- Earlier silent westerns

- Dime novel western stories

- Contemporary B-western conventions

This Film Influenced

- Later John Wayne westerns

- The undercover hero trope in westerns

- Revenge westerns of the 1930s-1950s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the public domain. Multiple copies exist in various archives and collections. The quality varies depending on the source material, but complete versions are available. The film has been released on DVD by multiple public domain distributors.