Where Are My Children?

"The picture that dares to tell the truth!"

Plot

Richard Walton, a successful District Attorney, desperately wants children but remains unaware that his wife Edith and her socialite circle have been secretly undergoing abortions to maintain their luxurious lifestyles. After successfully defending an author charged with publishing indecent literature about birth control, Walton becomes increasingly aware of social issues. When his sister-in-law dies from a botched abortion, Walton begins investigating the practices of local physicians, leading him to discover his own wife's multiple abortions. The film culminates in a powerful courtroom sequence where Walton prosecutes the doctors responsible, while Edith is left barren and remorseful. The story concludes with Walton receiving a vision of the souls of unborn children, including his own, as he grapples with the moral and social implications of his discoveries.

About the Production

Lois Weber wrote, directed, and co-produced this controversial film, which faced censorship challenges in several states. The film featured groundbreaking special effects for its time, including ethereal sequences depicting the souls of unborn children. Weber used actual medical professionals as consultants to ensure accuracy in the courtroom scenes. The production was shrouded in secrecy due to its controversial subject matter, with Universal initially hesitant to distribute it.

Historical Background

Made during the Progressive Era, 'Where Are My Children?' emerged at a time when birth control and women's reproductive rights were hotly debated topics. The 1915-1916 period saw the rise of the birth control movement led by Margaret Sanger, who was arrested for distributing contraceptive information. The film reflected growing concerns about urbanization, changing sexual mores, and the role of women in society. World War I was raging in Europe, though the United States had not yet entered the conflict. The film's release coincided with the height of the silent film era's artistic ambitions and the film industry's move toward longer, more complex feature films. Censorship boards were gaining power across the country, making the film's bold subject matter particularly risky.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents a landmark in American cinema as one of the first major studio productions to tackle abortion and birth control directly. It demonstrated Lois Weber's unique position as a female director addressing women's issues from a woman's perspective, though with a conservative moral framework. The film's commercial success proved that controversial social topics could draw audiences, paving the way for more socially conscious cinema. It sparked national debate about reproductive rights and the role of cinema in public discourse. The film is now recognized as a crucial example of early feminist filmmaking, despite its ultimately conservative message about abortion. Its preservation and restoration have made it an important document of early 20th century attitudes toward women's health and autonomy.

Making Of

Lois Weber approached this project with missionary zeal, believing cinema could be a force for social reform. She spent months researching medical and legal aspects of abortion and birth control, consulting with doctors and lawyers. The controversial nature of the subject caused tension with Universal executives, who initially refused to distribute it. Weber reportedly financed portions of the production herself to maintain creative control. The courtroom scenes were filmed in a single day with actual legal professionals serving as extras. The special effects sequence featuring the souls of unborn children was achieved through innovative double exposure techniques that took weeks to perfect. Weber insisted on using real medical instruments and authentic courtroom procedures to lend credibility to the production.

Visual Style

The cinematography by William G. Canfield employed innovative techniques for its time, including sophisticated use of lighting to create moral contrasts between scenes. The film featured groundbreaking special effects, particularly in the sequences depicting the souls of unborn children, which used double exposure and matte techniques. Canfield utilized deep focus photography in the courtroom scenes to capture the full scope of the proceedings. The lighting design emphasized the moral dichotomy between the bright, wholesome world Walton desires and the shadowy world of secrets his wife inhabits. The film's visual style combined realism in the courtroom and medical scenes with ethereal, dreamlike sequences that represented spiritual themes.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations, particularly in special effects. The sequence showing the souls of unborn children represented one of the earliest uses of double exposure for supernatural elements in narrative cinema. Weber employed sophisticated editing techniques to create parallel action sequences, cutting between the courtroom drama and flashbacks. The film's use of location shooting in actual courtrooms and medical facilities added authenticity rarely seen in studio productions of the era. The makeup effects for the dying sister-in-law were considered remarkably realistic for 1916. The film also featured innovative title card designs that incorporated statistical information about infant mortality and abortion rates.

Music

As a silent film, 'Where Are My Children?' featured no recorded soundtrack but was accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. Universal provided a detailed musical cue sheet suggesting appropriate pieces for various scenes. Recommended music included classical works by Chopin, Beethoven, and Wagner to underscore emotional moments. The cue sheet specifically suggested 'Moonlight Sonata' for the scenes of marital tension and more dramatic pieces for the courtroom sequences. Some theaters employed small orchestras while others used solo piano accompaniment. The musical accompaniment was crucial in conveying the film's emotional weight and moral themes to audiences.

Famous Quotes

"I have prosecuted many men for their crimes, but never did I dream I would have to prosecute those who should protect life." - Richard Walton

"The little souls that might have been... they will never know the warmth of a mother's love." - Vision sequence intertitle

"In our quest for social position, we have forgotten our most basic duty to life itself." - Edith Walton

"The law protects the living, but who protects those who might have lived?" - Courtroom intertitle

"Sometimes the greatest crimes are those committed in the name of progress and society." - Richard Walton

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic courtroom sequence where Walton prosecutes the abortionists while discovering his wife's complicity, featuring powerful performances and authentic legal proceedings

- The ethereal vision sequence where Walton sees the souls of unborn children, including his own, using groundbreaking double exposure effects

- The deathbed scene of Walton's sister-in-law following a botched abortion, which was considered shockingly realistic for its time

- The confrontation between Walton and his wife Edith when he discovers her secret, featuring intense emotional performances

- The opening sequence establishing Walton's desire for children and his happy marriage, before the dark secrets are revealed

Did You Know?

- Lois Weber was one of the few female directors in early Hollywood and the highest-paid director of her time, earning $5,000 per week

- The film was banned in Pennsylvania and faced censorship in several other states due to its controversial subject matter

- Tyrone Power Sr. was the father of the more famous Tyrone Power, who became a major star in the 1930s-1950s

- The film was re-released in 1917 under the title 'The Forbidden Woman' to attract new audiences

- Weber included actual statistics about infant mortality and abortion rates in the film's intertitles

- The film was one of the first to address birth control and abortion directly, though it took an anti-abortion stance

- Weber used a double exposure technique to create the ghostly sequences of unborn children

- The film's success led to Weber being given complete creative control over her subsequent projects

- Despite its controversial nature, the film was endorsed by several women's suffrage organizations

- The original negative was thought lost for decades until a print was discovered in the 1990s

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's courage and technical excellence. The New York Times called it 'a powerful and important work of cinema' while Variety noted its 'unflinching honesty and remarkable artistry.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a complex work that both advances and limits women's perspectives. The Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1994, calling it 'culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.' Film scholars now view it as a crucial example of early social problem cinema and evidence of women's significant contributions to early filmmaking. The film's moral complexity continues to generate scholarly debate about its ultimate stance on reproductive rights.

What Audiences Thought

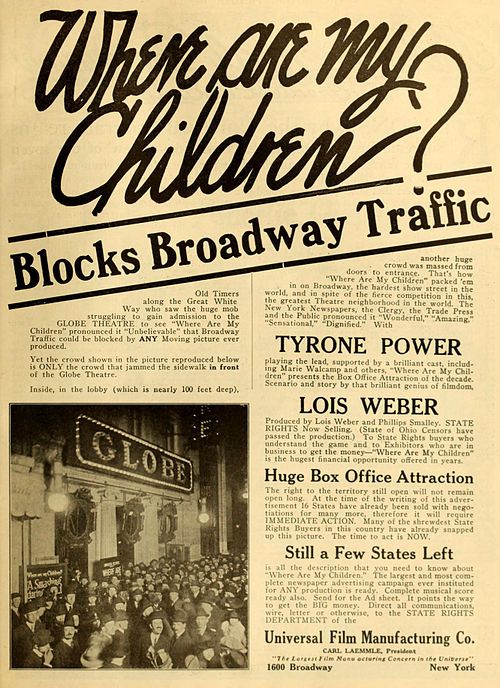

The film was a massive commercial success, drawing record crowds in major cities. Audience reactions were reportedly intense, with many women reportedly weeping during the courtroom sequences. The film sparked heated discussions in newspapers and social gatherings about its controversial themes. Some women's groups praised the film for addressing important issues, while others criticized its anti-abortion stance. The film's success led to increased public awareness of birth control and reproductive health issues. Contemporary accounts describe audiences leaving theaters in deep contemplation, with the film becoming a topic of conversation for weeks after viewing. The film's emotional impact was so strong that some theaters provided discussion guides for audience members.

Awards & Recognition

- 1916 National Board of Review Award - One of the Top Ten Films of the Year

- 1917 Motion Picture Magazine Medal - Best Picture of the Year

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The social problem plays of Henrik Ibsen

- Progressive Era reform movements

- Margaret Sanger's birth control activism

- D.W. Griffith's 'Intolerance' (1916)

- Thomas Edison's social reform films

This Film Influenced

- The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1917)

- The Unborn (1916)

- Mothers of Men (1917)

- The Blot (1921)

- The Scarlet Letter (1926)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for decades but a complete 35mm print was discovered in the 1990s. It has been restored by the Library of Congress and is preserved in their National Film Registry. The restored version includes original tinting and toning effects. A digitally restored version was released on DVD by Kino International in 2007. The film is considered one of the best-preserved examples of Lois Weber's work. The original negative no longer exists, but multiple complete prints survive in archives worldwide.