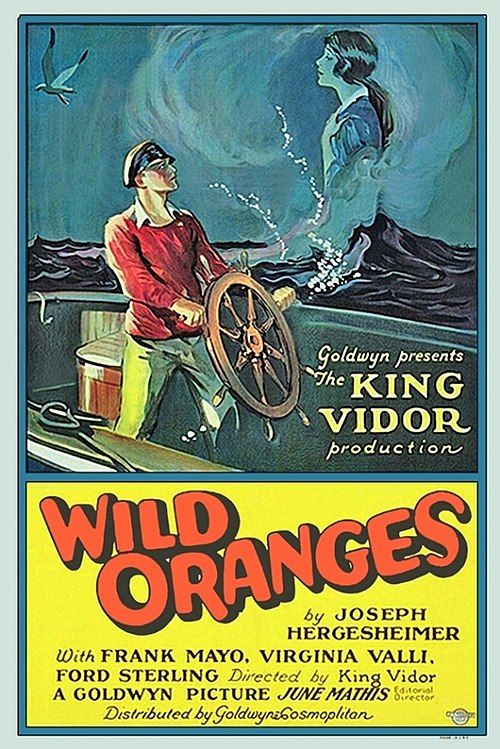

Wild Oranges

"A story of wild love on a wild island!"

Plot

Millie Stope lives a secluded existence with her grandfather on a remote Georgia island, where they cultivate wild oranges. Their isolated life is disrupted by Nicholas, a dangerous fugitive who has taken refuge on the island and terrorizes the family while developing an obsessive interest in Millie. The arrival of John Woolfolk, a widower sailing his yacht, brings hope and romance to Millie's life as they quickly fall in love. Nicholas's jealousy and violent nature threaten to destroy their budding relationship, leading to a tense psychological struggle on the isolated island. The film builds to a dramatic confrontation where the civilized world represented by John clashes with the primal forces embodied by Nicholas.

About the Production

Director King Vidor was particularly proud of this film's atmospheric qualities and considered it one of his most personal works. The production faced challenges filming on location at Catalina Island, where the crew had to deal with unpredictable weather and difficult terrain. The orange groves featured in the film were specially planted for the production. Vidor insisted on extensive location shooting to achieve the authentic, isolated atmosphere he wanted, which was unusual for the time when most films were shot entirely on studio sets.

Historical Background

Wild Oranges was produced during a transitional period in American cinema when films were becoming more sophisticated in their storytelling and psychological depth. 1924 was a peak year for silent film production, with Hollywood studios churning out hundreds of features annually. The film industry was consolidating under the studio system, with MGM establishing itself as a major powerhouse. This was also the year that the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) was strengthening its enforcement of the Hays Code, though it wouldn't be strictly enforced until the 1930s. The film's adult themes and psychological complexity reflect the artistic freedom that existed in pre-code cinema. The Roaring Twenties were in full swing, and audiences were increasingly sophisticated, demanding more than simple melodramas from their entertainment.

Why This Film Matters

Wild Oranges represents an important step in the evolution of American cinema toward more psychologically complex narratives. King Vidor's approach to character development and atmosphere influenced the film noir movement that would emerge a decade later. The film's exploration of themes like isolation, obsession, and the conflict between civilization and primal nature were ahead of their time for mainstream cinema. Its use of location shooting to enhance mood and atmosphere helped establish new standards for visual storytelling in American films. The movie also demonstrates the artistic possibilities that existed within the studio system before the strict enforcement of the Production Code, showing how filmmakers could explore adult themes with subtlety and sophistication.

Making Of

King Vidor fought hard with MGM executives to make this film, as they considered it too dark and psychological for mainstream audiences. Vidor saw the project as an opportunity to explore more mature themes and complex character psychology than was typical in silent cinema. The casting of Ford Sterling as the villain was particularly controversial, as he was primarily known for his work in Mack Sennett comedies. Vidor believed Sterling's expressive face would be perfect for the tormented Nicholas character, a gamble that paid off critically. The production spent nearly a month on Catalina Island, a significant expense at the time, but Vidor insisted the authentic location was essential to the film's atmosphere. The director worked closely with cinematographer John Arnold to develop a visual style that emphasized the contrast between the natural beauty of the island and the psychological darkness of the story.

Visual Style

John Arnold's cinematography was particularly praised for its innovative use of natural lighting and atmospheric effects. The film features extensive location photography on Catalina Island, allowing Arnold to capture the stark beauty of the coastal landscape. The cinematography emphasizes the isolation of the setting through wide shots that show the characters dwarfed by their surroundings. Arnold used soft focus techniques to create dreamlike sequences that contrast with the harsh reality of the island. The visual style employs strong shadows and silhouettes to enhance the psychological tension, prefiguring the film noir aesthetic that would emerge in the following decade. The orange grove scenes are particularly notable for their use of filtered sunlight to create an almost painterly effect.

Innovations

Wild Oranges was notable for its extensive use of location shooting at a time when most films were primarily studio-bound. The production pioneered techniques for filming in natural light conditions, using reflectors and filters to maintain visual consistency. The film's editing rhythm, particularly in the suspense sequences, was considered innovative for its time. Vidor and his cinematographer developed new methods for creating depth in outdoor scenes without the benefit of artificial lighting. The soundstage sequences were enhanced by the use of forced perspective to create the illusion of the island's isolation. The film also featured early examples of subjective camera techniques to represent the psychological states of the characters.

Music

As a silent film, Wild Oranges would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been compiled from classical pieces and mood music provided by the studio's music department. The film's romantic and suspenseful elements would have been underscored by appropriate musical selections. Unfortunately, no original cue sheets or specific musical documentation for the film's initial release survive. Modern screenings are typically accompanied by specially commissioned scores or improvisation by silent film accompanists. The film's atmospheric qualities make it particularly suitable for musical interpretation, with many modern musicians finding inspiration in its visual rhythms and emotional dynamics.

Famous Quotes

Nicholas: 'This island is mine... and everything on it.'

John Woolfolk: 'In the middle of nowhere, I found everything.'

Millie Stope: 'Some oranges are wild because no one has ever tended them... like some people.'

Grandfather Stope: 'The sea brings what it will, and takes what it wants.'

Memorable Scenes

- The tense confrontation between Nicholas and John in the orange grove at sunset, with the shadows of the trees creating a prison-like atmosphere

- Millie's first sighting of John's yacht on the horizon, representing hope and escape from her isolated existence

- Nicholas's obsessive watching of Millie through the window, filmed through distorted glass to emphasize his disturbed psychology

- The final chase sequence across the rocky island coastline, utilizing the natural landscape to enhance the dramatic tension

Did You Know?

- King Vidor considered this one of his most personal and artistically satisfying films from his silent era work

- The film was based on a short story by Joseph Hergesheimer titled 'Wild Oranges'

- Frank Mayo was not the first choice for the lead role; Vidor had to fight with the studio to cast him

- The island scenes were filmed on Catalina Island, which required the entire production company to relocate for several weeks

- Virginia Valli was one of MGM's top stars at the time and was loaned to Vidor's production unit specifically for this film

- The film's psychological intensity and adult themes were considered quite daring for 1924

- Ford Sterling, primarily known for comedy roles, played against type as the menacing Nicholas

- The original story was set in Florida but was changed to a Georgia island for the film adaptation

- Vidor used innovative camera techniques to create the claustrophobic feeling of island isolation

- The film was one of the first to extensively use natural lighting for outdoor scenes rather than relying solely on artificial lighting

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Wild Oranges for its artistic ambitions and atmospheric qualities. The New York Times review highlighted King Vidor's 'masterful direction' and the film's 'unusual psychological depth.' Variety noted that the film 'transcends the usual melodramatic conventions' with its sophisticated treatment of character motivation. Modern critics have rediscovered the film as an important example of Vidor's early artistic development. Film historian Kevin Brownlow has cited it as 'one of the most psychologically complex films of the silent era.' The film is now regarded as a significant work in Vidor's filmography, demonstrating his ability to work within the studio system while maintaining artistic integrity.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience response was mixed, with many viewers finding the film's psychological intensity unsettling compared to the more straightforward entertainments typical of the period. However, the film developed a strong following among more sophisticated urban audiences who appreciated its artistic qualities. The performances, particularly Ford Sterling's against-type casting as the villain, generated significant discussion among moviegoers. Over time, the film has gained appreciation among silent film enthusiasts and is now considered a cult classic among Vidor's work. Modern audiences at revival screenings have responded positively to the film's atmospheric qualities and psychological depth.

Awards & Recognition

- None - the film was released before the first Academy Awards ceremony

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The psychological dramas of German Expressionist cinema

- F.W. Murnau's 'Sunrise' (1927) which shared similar themes of nature versus civilization

- The literary works of Joseph Conrad, particularly 'Lord of the Jim'

- Swedish naturalist cinema of the 1920s

This Film Influenced

- King Vidor's later psychological dramas including 'The Crowd' (1928)

- The island thriller subgenre that would become popular in the 1930s

- Early film noir through its use of psychological tension and moral ambiguity

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Wild Oranges survives in complete form and has been preserved by major film archives. The Library of Congress holds a 35mm nitrate print in their collection. The film underwent restoration in the 1990s as part of a broader effort to preserve King Vidor's silent works. A restored version was screened at the 1995 Telluride Film Festival. The film is also held in the MGM/UA archives and has been transferred to safety film stock. While not as widely available as some silent classics, it is considered well-preserved for a film of its era, with good image quality in surviving prints.