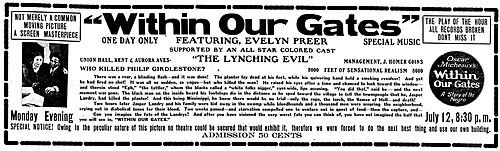

Within Our Gates

Plot

Sylvia Landry, an educated black woman, is abandoned by her fiancé and returns to the South to help save a near-bankrupt school for impoverished black children. Through flashbacks, we learn of Sylvia's traumatic past, including her discovery that she is the mixed-race daughter of a white senator who had an affair with her black mother, and her near-lynching by a white mob. The film portrays the harsh realities of racial violence and discrimination faced by African Americans in the early 20th century. Sylvia's dedication to education and her resilience in the face of tragedy become central to the narrative, ultimately leading to the school receiving crucial funding from a Northern benefactor. The story culminates in a dramatic confrontation where Sylvia is saved from another lynching attempt by her white half-brother, highlighting complex themes of racial identity and family ties across the color line.

About the Production

Shot in just three weeks with a combination of professional actors and non-professionals. Micheaux used innovative financing methods, including selling shares of his company door-to-door in black neighborhoods. The film faced significant censorship challenges in several cities due to its frank depiction of racial violence and miscegenation. Micheaux had to re-edit the film multiple times to satisfy local censorship boards, resulting in different versions being shown in different locations.

Historical Background

The film emerged during a turbulent period in American race relations, just after World War I when African American veterans returned to a country that still denied them basic rights. The Great Migration was underway, with millions of African Americans moving from the rural South to northern cities. Racial violence was rampant, with lynchings occurring regularly across the country. The NAACP was actively campaigning against lynching and racial discrimination. The film also responded directly to the controversy surrounding D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation,' which glorified the Ku Klux Klan and presented racist caricatures of African Americans. Micheaux's film was part of a broader movement of 'race films' - movies made by black filmmakers for black audiences - that sought to counter negative stereotypes and present more authentic representations of African American life.

Why This Film Matters

'Within Our Gates' represents a landmark in American cinema as the earliest surviving feature film by an African American director. It stands as a powerful counter-narrative to the racist depictions prevalent in mainstream Hollywood films of the era. The film's unflinching portrayal of racial violence, particularly the lynching scenes, was groundbreaking and courageous for its time. It established Oscar Micheaux as a pioneering voice in independent cinema and laid the groundwork for future generations of African American filmmakers. The film's exploration of complex themes like miscegenation, racial passing, and the importance of education for black advancement was revolutionary. Its rediscovery and restoration in the 1970s sparked renewed interest in Micheaux's work and the broader history of African American cinema. Today, it is studied in film schools and universities as a masterpiece of early American cinema and a crucial document of African American cultural history.

Making Of

Oscar Micheaux faced enormous challenges producing this film as an independent black filmmaker in 1920. Working with limited resources, he had to be resourceful, using local Chicago residents as extras and shooting on location rather than in expensive studios. The film's controversial subject matter, particularly its depiction of a white man's rape of a black woman and subsequent lynching attempt, led to fierce battles with censorship boards across the country. Micheaux was forced to create multiple versions of the film to satisfy different local requirements. Despite these obstacles, he managed to produce a technically sophisticated film that used flashbacks and cross-cutting techniques effectively. The production was so rushed that some scenes were reportedly shot in a single take. Micheaux's background as a novelist and homesteader influenced his storytelling approach, bringing literary techniques to his filmmaking.

Visual Style

The cinematography, while constrained by budget limitations, shows Micheaux's sophisticated visual storytelling. The film uses location shooting effectively, creating a sense of authenticity that studio films of the era often lacked. The lynching sequences employ dramatic lighting and camera angles to create tension and horror. Micheaux uses close-ups strategically to emphasize emotional moments, particularly in scenes featuring Evelyn Preer as Sylvia. The film's visual style incorporates elements of German Expressionism in its use of shadows and dramatic composition during tense scenes. Despite technical limitations, the cinematography serves the narrative effectively, using visual metaphors and symbolic imagery to enhance the story's themes. The restoration work has revealed the film's visual sophistication, which was obscured for decades in poor-quality prints.

Innovations

Despite its limited budget, the film demonstrates several technical innovations for its time. Micheaux's use of flashbacks to reveal Sylvia's backstory was sophisticated for 1920 cinema. The film employs cross-cutting between different storylines to build tension and create thematic connections. Micheaux developed efficient production techniques that allowed him to complete the film in just three weeks, a remarkable achievement for a feature of this complexity. The film's special effects, particularly in the lynching sequences, were accomplished using practical methods that created convincing illusions of danger. Micheaux's ability to create multiple versions of the film to satisfy different censorship requirements demonstrated technical adaptability. The preservation and restoration work done in the 1970s and 1990s also represents significant technical achievement in film conservation.

Music

As a silent film, 'Within Our Gates' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific musical scores used are not documented, but typical accompaniment for such films included piano or organ music, sometimes with small orchestras in larger theaters. Modern screenings have featured newly composed scores by contemporary musicians, including jazz and classical compositions that reflect the film's themes. The Library of Congress restoration includes a commissioned score that attempts to recreate the musical experience of the 1920s while acknowledging the film's historical significance. The absence of recorded sound makes the visual storytelling particularly powerful, with Micheaux relying on expressive acting and intertitles to convey the narrative and emotional content.

Famous Quotes

"Within our gates, the story of the Negro is told, not by others, but by ourselves." (Opening intertitle)

"Education is the key to our freedom and advancement." (School fundraising scene)

"The blood that runs in my veins is the same as yours." (Sylvia confronting her white father)

"We must build our own schools, for our children's future depends on it." (Sylvia's speech)

"In the North, they may not lynch us, but they still hate us." (Dialogue about Northern racism)

Memorable Scenes

- The lynching attempt sequence where Sylvia is saved at the last minute by her white half-brother, featuring dramatic cross-cutting between the mob and the rescue

- The flashback revealing Sylvia's parentage and the story of her mother's relationship with the white senator

- The scene where Sylvia discovers her fiancé's betrayal and decides to dedicate herself to the school

- The fundraising scene where Sylvia makes an emotional appeal for the school's survival

- The confrontation between Sylvia and her white father, who refuses to acknowledge their relationship

Did You Know?

- It is the earliest surviving feature film directed by an African American

- Created as a direct response to D.W. Griffith's racist epic 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915)

- The film was banned or heavily censored in several cities including Chicago and Omaha

- For decades, only a single incomplete print existed at the Library of Congress

- The film was rediscovered in Spain in the 1970s with Spanish intertitles, which were then translated back to English

- Director Oscar Micheaux sold shares of his production company door-to-door to finance the film

- Contains one of cinema's earliest depictions of a lynching attempt

- The film's title comes from a line in a Paul Laurence Dunbar poem

- Micheaux used both professional actors and amateurs from the local community

- The original negative was destroyed in a fire, making preservation efforts crucial

- It was Micheaux's second feature film after 'The Homesteader' (1919)

- The film features one of the first on-screen kisses between interracial characters in American cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary white critics largely ignored or dismissed the film, with some reviews in mainstream newspapers condescending or outright hostile. However, black newspapers like the Chicago Defender praised Micheaux's courage and artistic achievement. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a masterpiece of early cinema. The New York Times included it in their list of the 1,000 Best Films Ever Made. Film scholars now recognize its technical sophistication, particularly Micheaux's use of flashbacks and parallel editing. Critics note that despite its budget constraints, the film achieves remarkable emotional power and social commentary. The film is now celebrated for its boldness in tackling taboo subjects and its importance in film history as a work of resistance against racist representations in mainstream media.

What Audiences Thought

The film found its primary audience in segregated black theaters across the country, where it was received with enthusiasm and appreciation for its honest portrayal of African American life. Black audiences reportedly responded emotionally to scenes depicting racial injustice and celebrated the film's positive representations of educated, professional African Americans. Despite limited distribution due to censorship challenges, the film was successful enough to establish Micheaux as a significant figure in independent cinema. The film's controversial nature sometimes drew protests from white supremacist groups, which paradoxically increased its notoriety and attendance in some areas. Modern audiences at revival screenings and film festivals have responded with shock at the film's raw depiction of racial violence and admiration for its artistic courage.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915) - as a direct response and counter-narrative

- D.W. Griffith's filmmaking techniques

- Paul Laurence Dunbar's poetry

- Booker T. Washington's philosophy of education

- W.E.B. Du Bois's writings on racial identity

- Contemporary newspaper accounts of lynchings

- Micheaux's own novels and life experiences

This Film Influenced

- 'The Betrayal' (1948) - Micheaux's final film

- 'The Spook Who Sat by the Door' (1973)

- 'Do the Right Thing' (1989)

- 'Malcolm X' (1992)

- 'Rosewood' (1997)

- 'Get Out' (2017)

- 'BlacKkKlansman' (2018)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for decades until a print with Spanish intertitles was discovered in Spain in the 1970s. This version was preserved by the Library of Congress and later restored with English intertitles. The restoration process involved reconstructing missing scenes and improving image quality. The film is now preserved in the National Film Registry and is considered one of the most important surviving examples of early African American cinema. Multiple archives hold copies of the restored film, including the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The restoration has made the film accessible for scholarly study and public exhibition.