A Blind Retribution

Plot

A Blind Retribution tells the story of a young man who, wrongfully accused of a crime he did not commit, serves years in prison while his family suffers from social ostracism and poverty. Upon his release, he discovers that the true culprit has become a respected member of society, while his own family has been destroyed by the false accusations. Consumed by a desire for vengeance but blinded by his rage, the protagonist sets out to ruin the man who stole his life, only to discover that his retribution may not bring the peace he seeks. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation where justice and mercy collide, questioning whether true retribution can ever be achieved through blind revenge.

About the Production

A Blind Retribution was produced during the golden age of Italian cinema, when the country was one of the world's leading film producers. The film was shot on location in Rome using the natural lighting techniques common in early Italian cinema. Director Luigi Maggi was known for his meticulous attention to detail and his ability to extract powerful emotional performances from his actors, which was particularly challenging in the silent era. The production utilized the innovative camera techniques that Italian filmmakers were pioneering at the time, including mobile camera shots and sophisticated editing patterns that were advanced for 1911.

Historical Background

A Blind Retribution was produced in 1911, during what many film historians consider the golden age of Italian cinema. Italy was at this time one of the world's leading film producers, second only to France in output and influence. The country's film industry was centered in Rome and Turin, with studios like Cines pioneering new techniques in cinematography, editing, and production design. This period saw the emergence of the Italian historical epic, with films like Quo Vadis (1913) and Cabiria (1914) soon to follow. However, alongside these grand spectacles, Italian directors like Luigi Maggi were also producing intimate social dramas that explored contemporary themes. The film reflects the social tensions of pre-World War I Italy, a time of rapid industrialization, urbanization, and social upheaval. The themes of justice, wrongful accusation, and social ostracism would have resonated strongly with Italian audiences of the time, who were experiencing dramatic changes in their social structure and legal systems.

Why This Film Matters

A Blind Retribution represents an important example of early Italian social drama, a genre that would influence filmmakers across Europe and America. The film's exploration of themes like justice, revenge, and moral complexity helped establish the emotional depth and psychological sophistication that would become hallmarks of Italian cinema. While American films of the same period were often simpler in their moral outlook, Italian dramas like this one were willing to explore the gray areas of human motivation and social justice. The film also demonstrates the technical sophistication of Italian cinema in 1911, with its use of location shooting, natural lighting, and sophisticated editing techniques. This level of craftsmanship helped establish Italy's reputation for quality filmmaking that would persist throughout the silent era. The film's focus on social themes also prefigured the neorealist movement that would emerge in Italy decades later, showing how early Italian cinema was already concerned with realistic depictions of social problems.

Making Of

The production of A Blind Retribution took place during a remarkable period of creative expansion in Italian cinema. Director Luigi Maggi, who had transitioned from acting to directing just a few years earlier, brought his theatrical experience to bear on the film's dramatic structure. The cast, led by Paolo Azzurri, was drawn from the growing pool of professional Italian film actors who were developing new techniques for silent performance. The film was shot on the outskirts of Rome, taking advantage of the varied landscapes available near the Cines studio. Because this was before the advent of sophisticated sound recording equipment, the production relied entirely on visual storytelling, requiring Maggi to work closely with his cinematographer to ensure that emotions and plot points could be conveyed through gesture, expression, and composition. The film's themes of justice and retribution reflected the social concerns of early 20th-century Italy, a period of rapid modernization and social change.

Visual Style

The cinematography of A Blind Retribution demonstrates the sophisticated visual style that Italian filmmakers had developed by 1911. The film makes effective use of natural lighting, particularly in exterior scenes shot on location around Rome. The camera work shows remarkable mobility for the period, with pans and tracking shots that enhance the dramatic impact of key scenes. The composition of shots reflects the influence of Italian Renaissance painting, with careful attention to balance, perspective, and the use of light and shadow to create emotional atmosphere. The film also employs innovative editing techniques for its time, including cross-cutting between parallel actions to build tension and create dramatic irony. Close-ups are used strategically to emphasize emotional moments, a technique that was still relatively new in 1911. The visual style of the film helped establish the aesthetic standards for Italian dramatic cinema and influenced filmmakers across Europe.

Innovations

A Blind Retribution showcased several technical innovations that were advancing the art of cinema in 1911. The film employed sophisticated editing techniques, including cross-cutting and parallel action, that were still relatively new to cinema at the time. The use of location shooting rather than relying entirely on studio sets demonstrated the growing mobility of film equipment and the ambition of Italian producers. The film likely utilized the newly developed perforation system that allowed for more reliable film projection, reducing the risk of breaks during screening. The cinematography shows advanced understanding of lighting techniques, with effective use of both natural and artificial light to create mood and emphasize dramatic moments. The film's relatively long runtime for a drama of this period (12 minutes) allowed for more complex character development and plot progression than was typical in earlier cinema. These technical achievements helped establish Italian cinema as a leader in film production quality during the silent era.

Music

As a silent film, A Blind Retribution would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical presentation would have featured a pianist or small orchestra performing a score compiled from popular classical pieces and original compositions. The music would have been carefully synchronized with the on-screen action, with different musical themes representing the main characters and emotional states. Dramatic moments would have been emphasized with stirring musical passages, while tense scenes would have been accompanied by more dissonant or agitated music. The score would have been different for each theater, as musicians would adapt their performance to the size of the venue and the available instruments. Some larger theaters might have even employed special sound effects to enhance key moments in the narrative. The original musical scores for most films of this period have been lost, but modern restorations are typically accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the musical experience of early cinema audiences.

Famous Quotes

Justice delayed is justice denied

Blind vengeance sees no truth

The innocent suffer while the guilty prosper

Memorable Scenes

- The protagonist's dramatic return from prison, his face showing years of suffering and hardened resolve; The tense confrontation between the wronged man and his accuser, where truth and lies collide in a battle of wills; The emotional climax where the protagonist must choose between revenge and mercy, his internal struggle visible through his expressive performance; The final scene showing the consequences of blind retribution on all involved, leaving audiences to ponder the nature of true justice.

Did You Know?

- Luigi Maggi was one of Italy's pioneering directors, having started his career as an actor before moving behind the camera in 1908

- The film was produced by Società Italiana Cines, one of Italy's most important early film studios founded in 1906

- 1911 was a significant year for Italian cinema, marking the country's emergence as a major international film power

- Paolo Azzurri was a regular collaborator with Luigi Maggi, appearing in several of his films during this period

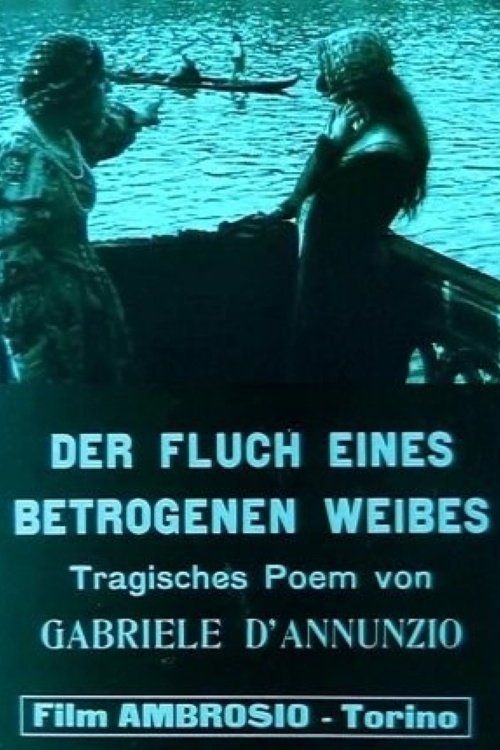

- The film's title in Italian was 'Una vendetta cieca', which directly translates to 'A blind vengeance'

- Early Italian dramas like this one were known for their emotional intensity and moral complexity

- The film was likely hand-colored in certain scenes, a common practice for important Italian productions of this era

- Italian films of 1911 were typically longer and more sophisticated than their American counterparts

- The film was distributed internationally, helping establish Italy's reputation for dramatic cinema

- Luigi Maggi was particularly known for his social dramas that explored themes of justice and morality

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of A Blind Retribution was generally positive, with Italian film journals of the time praising its emotional power and technical sophistication. Critics noted the strength of Paolo Azzurri's performance in the lead role, highlighting his ability to convey complex emotions through gesture and expression alone. The film's moral complexity was also appreciated, with reviewers noting how it went beyond simple melodrama to explore deeper questions of justice and redemption. International critics, particularly in France and England, also reviewed the film favorably, using it as evidence of Italy's growing importance in world cinema. Modern film historians view A Blind Retribution as an important example of early Italian dramatic cinema, noting how it demonstrates the sophistication of Italian filmmaking long before the more famous historical epics of the 1910s. The film is often cited in studies of early cinema as an example of how silent film could achieve remarkable emotional depth and narrative complexity without dialogue.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audience response to A Blind Retribution was reportedly strong, with the film finding success both in Italy and in international markets. Italian audiences of the time were particularly drawn to the film's emotional intensity and its exploration of themes that resonated with their own experiences of social change and legal uncertainty. The film's dramatic climax reportedly generated strong reactions in theaters, with audiences responding audibly to the emotional revelations and moral dilemmas presented on screen. The film's success in export markets, particularly in France and England, demonstrated the growing international appeal of Italian cinema. Modern audiences, when able to view the film through archival screenings or restorations, often express surprise at the sophistication of its storytelling and the power of its performances, challenging common assumptions about the primitive nature of early cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian theatrical tradition

- French melodrama

- Social realist literature

- Shakespearean tragedy

- Verismo opera tradition

This Film Influenced

- Later Italian social dramas

- American film noir themes of wrongful accusation

- European art cinema moral complexity

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

A Blind Retribution is considered a partially lost film, with only fragments surviving in various film archives. Some sequences are preserved at the Cineteca Italiana in Milan and the British Film Institute, but the complete film has not survived. This is unfortunately common for films of this era, as the unstable nitrate film stock used at the time deteriorated rapidly, and many early films were not considered worth preserving by their producers. The surviving fragments have been digitally restored and are occasionally screened at specialized film festivals and museum retrospectives dedicated to early cinema.