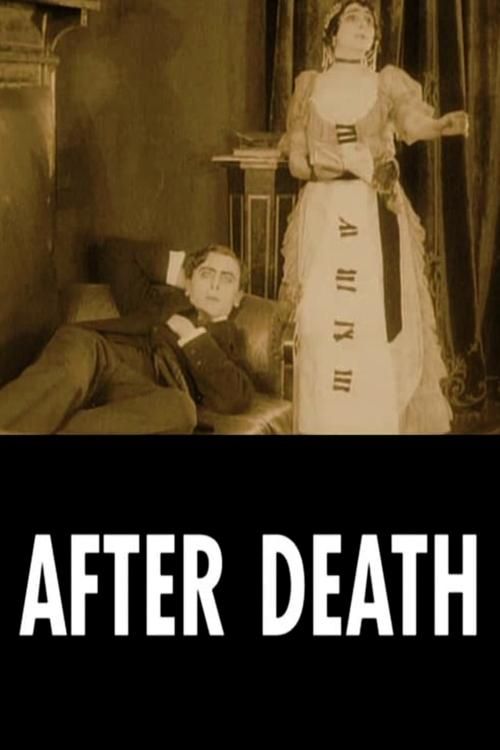

After Death

Plot

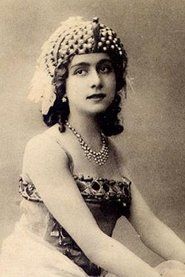

Young scholar Andrei becomes fascinated with the renowned actress Zoia Kadmina after watching her performances. When she unexpectedly sends him a note requesting a meeting, they have a brief but meaningful encounter that deeply affects Andrei. Three months later, Andrei is devastated to learn of Zoia's sudden death, and his fascination transforms into an obsessive fixation on her memory. He begins collecting everything related to her - photographs, reviews, and personal belongings - while attempting to reconstruct her life through the people who knew her. His obsession grows increasingly intense as he seeks to understand the woman behind the performer, ultimately blurring the line between memory and reality in his quest to keep her spirit alive.

About the Production

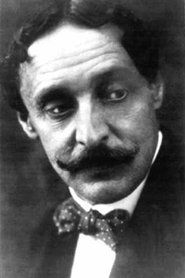

Filmed during the height of Russian cinema's golden age before the Bolshevik Revolution. The production utilized the Khanzhonkov studio's advanced facilities for the time. Director Yevgeni Bauer was known for his innovative use of lighting and camera movement, which were particularly evident in this production. The film was shot during summer 1915 when the Russian film industry was experiencing unprecedented creative freedom despite the ongoing World War I.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a pivotal moment in Russian history - 1915, during World War I but two years before the Bolshevik Revolution would transform the nation. The Russian Empire's film industry was experiencing a golden age of creativity and technical innovation, with directors like Bauer pushing the boundaries of cinematic art. This period saw Russian cinema achieving international recognition for its artistic sophistication, particularly in psychological drama and visual storytelling. The film's themes of obsession, death, and memory resonated deeply with Russian audiences, who were living through the trauma of war and facing an uncertain future. The cultural atmosphere was heavily influenced by Symbolist literature and philosophy, which emphasized the mystical and psychological dimensions of human experience. Cinema was still a relatively new art form, but Russian filmmakers were quickly establishing it as a serious medium for artistic expression.

Why This Film Matters

'After Death' represents a crucial milestone in the development of cinematic language, particularly in its sophisticated approach to psychological storytelling. The film's exploration of obsession and memory prefigured later surrealist and psychological horror traditions in cinema. Director Yevgeni Bauer's innovative use of lighting, camera movement, and editing techniques influenced generations of filmmakers, though many of his works were lost or suppressed after the revolution. The film exemplifies the remarkable artistic sophistication of pre-revolutionary Russian cinema, which was unfortunately largely unknown to Western audiences due to political isolation. Its themes and visual style anticipated the German Expressionist movement that would emerge several years later. The surviving fragments of the film continue to be studied by film historians as examples of early cinematic mastery of psychological narrative. The film represents a bridge between literary traditions of 19th-century Russia and the emerging language of cinema.

Making Of

The making of 'After Death' represented the peak of pre-revolutionary Russian cinema sophistication. Director Yevgeni Bauer was known for his meticulous attention to detail and innovative techniques that were years ahead of contemporary Western cinema. He employed complex lighting setups to create mood and atmosphere, using shadows and light to psychological effect. The casting of Vitold Polonsky as Andrei was particularly significant, as the actor had a reputation for portraying sensitive, intellectual characters with depth. The production took place at the Khanzhonkov studio in Moscow, which was equipped with state-of-the-art facilities for 1915. Bauer's direction emphasized psychological realism over melodrama, requiring subtle performances from his actors. The film's dream sequences were particularly challenging to create, requiring innovative camera techniques and double exposure effects that were cutting-edge for the period.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'After Death' was groundbreaking for its time, featuring sophisticated use of lighting and shadow to create psychological atmosphere. Director Yevgeni Bauer employed innovative camera movements and angles to convey emotional states and subjective experiences. The film made extensive use of chiaroscuro lighting effects that would later become associated with German Expressionist cinema. The dream sequences utilized double exposure and other special effects to create surreal, otherworldly imagery. The cinematography emphasized psychological realism through careful composition and lighting that reflected the characters' emotional states. The visual style was influenced by Russian Symbolist painting and photography, with its emphasis on mood and atmosphere. The surviving footage demonstrates remarkable technical sophistication in its use of focus and depth of field.

Innovations

The film showcased several technical innovations that were ahead of their time. Bauer's use of moving camera shots was particularly advanced for 1915, creating a sense of fluidity and psychological immersion. The film's lighting techniques were revolutionary, employing complex setups to create mood and atmosphere. The dream sequences featured innovative special effects using double exposure and in-camera tricks. The editing style was sophisticated, using cross-cutting and montage to create psychological connections between scenes. The film demonstrated an advanced understanding of visual storytelling through composition and movement. These technical achievements represented some of the most sophisticated filmmaking techniques of the era.

Music

As a silent film, 'After Death' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have been a pianist or small ensemble playing classical pieces or improvised music to match the film's mood. The score likely included works by Russian composers such as Tchaikovsky or Rachmaninoff, whose romantic and melancholic compositions suited the film's themes. The musical accompaniment would have been crucial in conveying the psychological tension and emotional depth of the narrative. Modern screenings of the surviving fragments are often accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the emotional impact of the original performances.

Famous Quotes

Silent films from this era did not contain recorded dialogue, but intertitles would have conveyed key narrative points and emotional states through written text

Memorable Scenes

- The dream sequence where Andrei imagines conversations with the deceased Zoia, utilizing innovative double exposure techniques to create ghostly, ethereal imagery that blurs the line between memory and hallucination

Did You Know?

- Director Yevgeni Bauer was one of the most sophisticated filmmakers of his era, often compared to D.W. Griffith for his technical innovations

- The film was based on a story by Ivan Turgenev, though adapted significantly for the screen

- Vitold Polonsky, who played Andrei, was one of the most popular leading men in Russian cinema before the revolution

- The film's exploration of psychological obsession was remarkably advanced for its time

- Only fragments of the complete film survive today, though enough remains to appreciate Bauer's artistic vision

- The film was one of over 80 films Bauer directed during his prolific career before his death in 1917

- The Khanzhonkov Company was the largest and most prestigious film studio in the Russian Empire

- The film's themes of death and obsession reflected the morbid fascination of Russian Symbolist literature

- Olga Rakhmanova, who played Zoia Kadmina, was known for her ethereal screen presence

- The film was released just two years before the Russian Revolution would dramatically transform the country's film industry

What Critics Said

Contemporary Russian critics praised the film for its psychological depth and technical sophistication, with particular admiration for Bauer's direction and Polonsky's performance. The film was noted for its departure from melodramatic conventions in favor of more subtle, psychological storytelling. Modern film historians consider 'After Death' one of Bauer's masterpieces and a landmark of early cinema. Critics have highlighted the film's innovative use of lighting and camera movement to convey psychological states. The film's exploration of obsession and memory has been analyzed as remarkably ahead of its time. Contemporary scholars often cite it as evidence of the sophistication of pre-revolutionary Russian cinema. The surviving fragments continue to impress critics with their visual poetry and psychological complexity.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well received by Russian audiences in 1915, who appreciated its sophisticated approach to psychological drama. The themes of love, death, and obsession resonated strongly with viewers living through the turmoil of World War I. Vitold Polonsky's performance as the obsessed scholar was particularly praised by audiences. The film's artistic ambitions were appreciated by the growing urban middle class that formed the core of cinema audiences in major Russian cities. The film's success helped establish psychological drama as a respected genre in Russian cinema. Contemporary audience reactions were recorded in film magazines of the period, which noted the film's powerful emotional impact. The film's reputation among Russian film enthusiasts has endured through the decades despite its incomplete survival.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Russian Symbolist literature

- Ivan Turgenev's stories

- German Romanticism

- Fyodor Dostoevsky's psychological novels

- Edgar Allan Poe's tales of obsession and death

This Film Influenced

- German Expressionist films of the 1920s

- Alfred Hitchcock's psychological thrillers

- Ingmar Bergman's psychological dramas

- Andrei Tarkovsky's poetic cinema

- David Lynch's surrealist films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives only in incomplete fragments, with approximately 20-30 minutes of footage preserved in various film archives. The surviving material is held by the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia and has been partially restored. The incomplete nature of the survival makes it difficult to appreciate the full scope of Bauer's original vision, but the remaining footage demonstrates the film's technical and artistic sophistication. The film is considered partially lost, though enough remains to study its significance in cinema history.