Anton Ivanovich Gets Angry

"Where high art meets popular entertainment in a symphony of understanding"

Plot

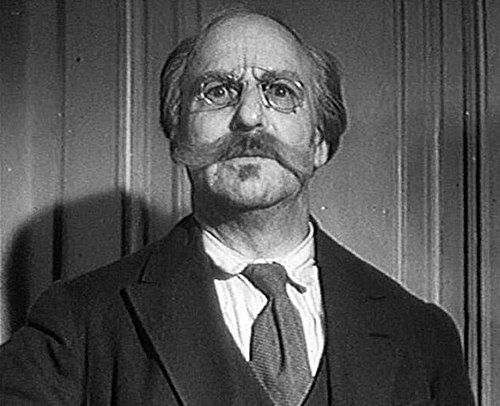

Anton Ivanovich Voronov is a distinguished professor at the Moscow Conservatoire who holds the music of Johann Sebastian Bach as the supreme standard against which all other musical works must be measured. His daughter Serafima, a talented young singer, infuriates her father by choosing to perform in an operetta composed by Aleksei Mukhin rather than pursuing what he considers the more noble path of opera. Despite his initial disapproval, Professor Voronov begins to see the artistic merit in Mukhin's work, which demands exceptional skill from its performers. The professor's transformation is completed when he dreams of an encounter with Bach himself, who tells him that 'people need all kinds of music,' finally convincing him that operetta and popular musical forms have their own legitimate artistic value.

About the Production

The film was completed just before the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. The production faced significant challenges as it was made during the tense pre-war period when resources were being diverted to military preparations. The musical sequences required sophisticated recording techniques for the time, and the dream sequence featuring Bach involved innovative special effects and lighting to create an ethereal atmosphere.

Historical Background

The film was produced and released in 1941, a pivotal year in world history and Soviet cinema. Created just before Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the film represents one of the last examples of pre-war Soviet popular cinema. The early 1940s saw increasing state control over artistic production, but also a demand for entertainment that could boost public morale. The film's themes of artistic reconciliation and the value of different forms of cultural expression reflected ongoing debates within Soviet cultural policy about the relationship between 'high art' and 'mass culture.' The timing of its release meant that many Soviet citizens would see this lighthearted comedy just before facing the immense hardships of war, making it a poignant reminder of pre-war normalcy.

Why This Film Matters

The film holds an important place in Soviet cinema history as a sophisticated musical comedy that successfully blended entertainment with artistic substance. It helped establish Lyudmila Tselikovskaya as a major star and demonstrated that Soviet cinema could produce musical films comparable to those being made in Hollywood. The film's message about the legitimacy of different musical genres resonated with Soviet cultural policy, which sought to make art accessible to the masses while maintaining high artistic standards. Its dream sequence featuring Bach became iconic in Soviet cinema and has been referenced and parodied in subsequent Russian films. The movie also represents a high point of the Leningrad film school before the devastation of World War II.

Making Of

The production of 'Anton Ivanovich Gets Angry' took place during a critical period in Soviet history. Director Aleksandr Ivanovsky, a veteran of Russian cinema since the silent era, brought his extensive experience to this musical comedy. The casting of Lyudmila Tselikovskaya as Serafima proved to be a masterstroke - she was relatively unknown at the time but her performance and singing abilities made her an overnight sensation. The musical sequences required extensive preparation, with the cast undergoing months of vocal training. The film's elaborate dream sequence, where Bach appears to the professor, was shot using special lighting effects and multiple exposures to create a supernatural atmosphere. The production team worked under pressure as the international situation deteriorated, and the film was completed mere months before the Soviet Union entered World War II.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Vladimir Rapoport employed sophisticated techniques for its time, particularly in the musical sequences and dream scenes. The camera work during the performance scenes used dynamic movements that captured the energy of the musical numbers. The dream sequence featuring Bach utilized innovative lighting techniques, including soft focus and backlighting, to create an ethereal, otherworldly atmosphere. The conservatoire scenes were shot with a more formal, classical style to reflect the academic setting, while the operetta sequences featured more vibrant, colorful cinematography. The contrast between these visual styles reinforced the film's themes about different musical genres.

Innovations

The film featured several technical innovations for Soviet cinema of the early 1940s. The sound recording for the musical numbers utilized multiple microphone techniques to capture both vocals and orchestral accompaniment with clarity. The dream sequence employed pioneering special effects, including double exposure and innovative lighting setups, to create the supernatural appearance of Bach. The film's editing, particularly in the musical sequences, used rhythmic cutting that synchronized with the music, a technique that was relatively advanced for the time. The production also overcame challenges related to filming musical performances, requiring synchronization between playback and live performance that was technically demanding for Soviet studios of this era.

Music

The film's score was a sophisticated blend of classical pieces and original compositions. The soundtrack prominently featured works by Bach, reflecting the professor's musical preferences, alongside original operetta numbers composed for the film. The musical numbers were carefully integrated into the narrative, advancing the plot while showcasing the performers' talents. The sound recording was particularly advanced for Soviet cinema of 1941, with clear reproduction of both dialogue and musical performances. The song from the dream sequence, where Bach sings about the need for all kinds of music, became one of the most memorable pieces from the film. The soundtrack was later released on records and became popular in its own right.

Famous Quotes

People need all kinds of music

Bach in the dream sequence,

Bach is the yardstick by which all music must be measured

Professor Voronov,

Opera is not just entertainment, it is art!

Professor Voronov,

Even the greatest composers wrote for the people, not just for the academy

Aleksei Mukhin

Music that touches the heart is never low, no matter how simple

Serafima

Memorable Scenes

- The dream sequence where Johann Sebastian Bach appears to Professor Voronov in his study, surrounded by ethereal light and floating musical notes, delivering the film's central message about the value of all musical genres. This scene uses innovative special effects for the time and serves as the emotional and thematic climax of the film.

Did You Know?

- This was Lyudmila Tselikovskaya's breakthrough role, launching her to become one of Soviet cinema's most beloved actresses of the 1940s

- Director Aleksandr Ivanovsky was already 60 years old when he made this film, bringing decades of experience in both silent and sound cinema

- The film's release coincided with the 250th anniversary of Bach's death (1685-1750), though this was likely coincidental

- The musical numbers were recorded using the latest Soviet sound technology of the time, with multiple takes required to achieve the desired quality

- Pavel Kadochnikov, who played the composer Mukhin, later became one of the Soviet Union's most respected dramatic actors

- The film was one of the last major productions completed by Lenfilm before the Siege of Leningrad began

- Many of the film's original negatives and prints were lost during World War II, with only partial copies surviving

- The dream sequence with Bach was considered technically ambitious for Soviet cinema of the early 1940s

- The film's message about the value of different musical genres reflected ongoing cultural debates in the Soviet Union about accessibility versus artistic merit

- Despite being a comedy, the film contains serious discussions about music theory and the nature of art

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its wit, musical sophistication, and performances. Pravda and other official newspapers highlighted how the film successfully combined entertainment with educational value about music. The performances, particularly Tselikovskaya's debut, were universally acclaimed. Modern critics and film historians view 'Anton Ivanovich Gets Angry' as a classic of Soviet musical cinema, noting its clever script, memorable songs, and the way it navigated the complex relationship between elite and popular culture. The film is often cited as an example of how Soviet cinema could produce sophisticated entertainment that still aligned with cultural values of the era.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Soviet audiences upon its release in 1941. Movie theaters reported sold-out screenings, and the songs from the film became widely popular, with people singing them in public spaces. Lyudmila Tselikovskaya's performance made her an instant star, and she received fan mail from across the Soviet Union. The film's humor and music provided welcome entertainment during increasingly tense times. Even during the war years, the film continued to be shown where possible, and it remained a beloved classic in the post-war Soviet period. Today, it is remembered fondly by older generations of Russians and has found new audiences through film festivals and retrospectives of Soviet cinema.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Degree (1941)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Traditional Russian musical theater

- European operetta traditions

- Soviet realist cinema conventions

- Hollywood musical films of the 1930s

- Bach's actual musical compositions

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet musical comedies of the 1940s-1950s

- Post-war Soviet films featuring dream sequences

- Musical films about artistic conflicts

- Soviet films featuring classical musicians as protagonists

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially preserved - Some original elements were lost during World War II and the Siege of Leningrad. The film exists in restored versions compiled from surviving prints and fragments, with some scenes possibly incomplete. The Gosfilmofond of Russia holds the most complete surviving version and has undertaken restoration efforts. Audio quality varies in surviving copies, particularly for the musical sequences.