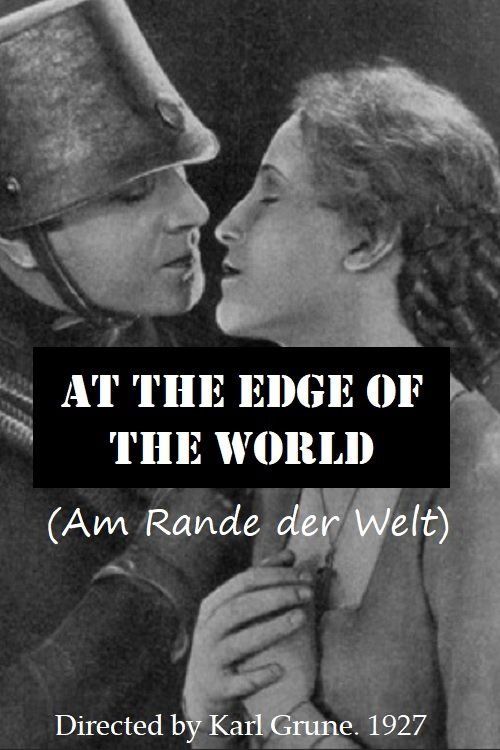

At the Edge of the World

Plot

At the Edge of the World tells the story of a remote mill situated precariously on the border between two unnamed countries, serving as both a physical and metaphorical dividing line. The mill's residents, including the miller and his family, live in relative isolation until political tensions escalate and war becomes imminent. As the conflict approaches, the characters find themselves torn between their peaceful existence and the demands of nationalism, with love and loyalty tested across the border. The film explores how ordinary people become pawns in the machinations of war, with the mill serving as a microcosm of the larger world conflicts. Ultimately, the story serves as a powerful anti-war statement, showing how arbitrary borders and political ambitions can destroy human relationships and peaceful communities.

About the Production

The film was produced during the peak of German Expressionist cinema, though it incorporated more realistic elements than earlier Expressionist works. Director Karl Grune was known for his meticulous attention to visual detail and often used natural locations alongside studio sets. The border mill set was an elaborate construction designed to emphasize the liminal space between the two countries. The production faced challenges due to the economic instability in Weimar Germany, which affected funding and resources.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1927 during the Weimar Republic, a period of intense cultural flowering in Germany despite economic and political instability. This was the same year that saw the release of other German cinematic masterpieces like 'Metropolis' and 'Berlin: Symphony of a Great City'. Germany was still deeply affected by World War I (1914-1918), with many veterans dealing with physical and psychological trauma, and the controversial Treaty of Versailles continuing to cause resentment. The period saw the rise of both artistic innovation and political extremism, with the Nazi Party gaining ground. The film's pacifist themes were particularly relevant as Europe was experiencing a fragile peace, and many feared another international conflict. The late 1920s also saw the transition from silent to sound films, making this one of the last major silent productions in Germany before the talkie revolution.

Why This Film Matters

'At the Edge of the World' represents an important example of German cinema's engagement with political and social themes during the Weimar period. As an anti-war film, it contributed to the broader cultural movement in Germany that sought to process the trauma of World War I and warn against future conflicts. The film's use of the border as a metaphor for division and conflict prefigured many later cinematic treatments of the Cold War and other geopolitical divisions. It also exemplifies the sophisticated visual storytelling techniques developed in German cinema, blending Expressionist influences with more realistic approaches. The film's prohibition by the Nazi regime highlights its perceived power as a political statement and its role in the broader cultural resistance to fascism. Today, it stands as an important artifact of Weimar cinema and a reminder of the artistic and political freedoms that existed briefly in Germany before the Nazi takeover.

Making Of

The production of 'At the Edge of the World' took place during a tumultuous period in German history, with the Weimar Republic facing economic challenges and political polarization. Director Karl Grune assembled a talented cast, including the rising star Brigitte Helm, who was at the height of her fame following 'Metropolis'. The filming required elaborate sets, particularly the mill that straddled the border between two fictional countries. The production team spent considerable time creating a realistic border environment, complete with customs posts and distinct national characteristics on each side. William Dieterle, who would later emigrate to Hollywood and become a successful director, brought his acting experience to create a nuanced performance. The film's anti-war message was considered bold for its time, as Germany was still grappling with the trauma of World War I and the controversial Treaty of Versailles. The cinematography employed both location shooting and studio work, blending naturalistic elements with the dramatic lighting characteristic of German Expressionism.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Carl Hoffmann employed sophisticated techniques characteristic of late Weimar cinema, blending Expressionist influences with emerging realist tendencies. The film made effective use of chiaroscuro lighting to create dramatic tension, particularly in scenes emphasizing the division between the two countries. The mill setting was filmed to emphasize its liminal quality, with careful composition to show how it literally straddled the border. Hoffmann used both static and moving camera shots to create visual variety, with tracking shots following characters as they moved between the two sides of the border. The cinematography paid particular attention to the contrast between the peaceful mill environment and the encroaching military presence, using visual metaphors to reinforce the film's themes. The black and white photography created stark contrasts that enhanced the emotional impact of key scenes, particularly those involving the disruption of the mill's peaceful existence.

Innovations

The film demonstrated several technical innovations for its time, particularly in its sophisticated use of set design to create the border mill environment. The production employed advanced matte painting techniques to extend the physical sets and create the illusion of a vast border region. The film's editing was notably advanced for 1927, using cross-cutting techniques to build tension between the different sides of the border. The lighting design incorporated both studio and natural lighting techniques to create a consistent visual style. The production also made innovative use of location shooting combined with studio work, a technique that was becoming more sophisticated in late Weimar cinema. The film's special effects, while subtle by modern standards, were effective in creating the sense of a divided landscape and the encroaching threat of war.

Music

As a silent film, 'At the Edge of the World' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical German cinema of 1927 would have featured a full orchestra for major productions like this one. The original score likely incorporated popular classical pieces along with specially composed music to enhance the dramatic moments. The music would have been particularly important during scenes without intertitles, helping to convey emotion and advance the narrative. While the original score has not survived, modern screenings of restored versions typically feature newly composed music or carefully selected period-appropriate pieces. The musical accompaniment would have emphasized the film's emotional arc, from peaceful beginnings through rising tension to dramatic climax.

Famous Quotes

Borders are lines drawn on maps by men who have never lived on them.

In war, the first casualty is not truth, but humanity.

A mill that grinds grain cannot grind guns without breaking itself.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence establishing the mill's precarious position on the border, with characters moving freely between the two countries before tensions rise

- The scene where military forces first arrive at the border, disrupting the peaceful life of the mill

- The emotional climax where characters must choose between their personal relationships and their national loyalties

- The final scenes showing the aftermath of conflict and the cost of war on ordinary lives

Did You Know?

- Brigitte Helm, who stars in this film, was also famous for her dual role as Maria and the Maschinenmensch in Fritz Lang's 'Metropolis' (1927), released the same year

- William Dieterle, who appears as an actor in this film, later became a prominent Hollywood director, known for films like 'The Life of Emile Zola' (1937)

- Director Karl Grune was one of the prominent figures in Weimar cinema, known for his innovative visual storytelling techniques

- The film's anti-war themes were particularly resonant in 1927 Germany, as the country was still recovering from World War I and experiencing political instability

- The mill setting was inspired by real border situations in Europe following the Treaty of Versailles, which had created many new international boundaries

- The film was one of the last major silent productions before German cinema began transitioning to sound

- Cinematographer Carl Hoffmann also worked on other notable German classics including 'The Blue Angel' (1930)

- The film's original German title was 'Am Rande der Welt'

- Despite its artistic merits, the film was banned by the Nazi regime in 1933 due to its pacifist themes

- The border concept was innovative for its time, prefiguring later Cold War cinema that would use borders as central metaphors

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1927 praised the film for its powerful anti-war message and technical achievements. German film journals of the period noted its effective use of the border setting as a metaphor and the strong performances, particularly Brigitte Helm's portrayal. International critics recognized it as part of the golden age of German cinema, comparing it favorably with other socially conscious films of the era. Modern film historians have reassessed the work as an important but often overlooked example of Weimar cinema's engagement with political themes. Critics have noted how the film anticipates later border films and its sophisticated blending of Expressionist visual style with realist narrative concerns. The film is now recognized as an important work in the career of Karl Grune and a significant example of German silent cinema's social consciousness.

What Audiences Thought

Upon its release in 1927, the film resonated strongly with German audiences who were still processing the effects of World War I and the ongoing political instability of the Weimar Republic. Many viewers connected with the film's pacifist message and its portrayal of ordinary people caught in political conflicts beyond their control. The presence of Brigitte Helm, fresh from her success in 'Metropolis', likely drew additional audiences to theaters. However, the film's serious tone and political themes may have limited its commercial success compared to more escapist entertainment of the period. As political tensions increased in Germany during the early 1930s, the film's message became more controversial, and it was eventually banned by the Nazi regime. Modern audiences who have seen the film at retrospectives or in restored versions generally appreciate its artistic merits and historical significance, though its relative obscurity means it has not achieved the widespread recognition of other Weimar classics.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionism

- Post-WWI German literature

- Pacifist movements of the 1920s

- Weimar Republic cinema

- Fritz Lang's visual style

- F.W. Murnau's narrative techniques

This Film Influenced

- Later border films of the 1930s

- German anti-war films of the early 1930s

- Cold War border cinema

- Political allegory films

- European art cinema of the 1950s-60s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered partially lost, with only fragments and some complete reels surviving in various film archives. Some portions exist in the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin and other European film archives. Restoration efforts have been ongoing, but a complete version of the film as originally released may no longer exist. The surviving footage has been preserved and occasionally screened at film retrospectives and silent film festivals.