Bed and Sofa

Plot

In cramped Moscow living conditions during the 1920s, construction worker Kolya and his wife Lyuda share a small apartment where their marriage has grown stale and routine. When Kolya's old friend Volodya, a printing press worker, arrives in Moscow and needs a place to stay, the couple invites him to sleep on their sofa, creating an uncomfortable ménage à trois. As Kolya works long hours, Lyuda and Volodya develop a romantic connection that leads to an affair, with Lyuda becoming pregnant and uncertain which man is the father. The situation escalates when Kolya discovers the infidelity, leading to a tense confrontation where both men must confront their roles in the situation. In a remarkably progressive conclusion for its era, Lyuda decides to leave both men and seek independence, choosing to raise her child alone rather than remain in a compromised situation.

About the Production

The film was shot during a period of relative artistic freedom in Soviet cinema before Stalin's cultural restrictions tightened. Director Abram Room was part of the avant-garde movement in Soviet film. The cramped apartment set was meticulously designed to reflect the real housing shortages in Moscow during the NEP (New Economic Policy) period. The film's controversial content required careful navigation of Soviet censorship boards, though it ultimately passed with minimal cuts.

Historical Background

Bed and Sofa was produced during the NEP (New Economic Policy) period in Soviet history (1921-1928), a time of relative cultural liberalization and artistic experimentation following the Russian Revolution and Civil War. This era saw the emergence of avant-garde movements in all arts, including cinema, with filmmakers like Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov pushing the boundaries of film language. The film directly addresses the housing crisis in Moscow, where rapid industrialization and urbanization led to extreme overcrowding, with multiple families often sharing single apartments. The 1920s also saw significant changes in gender roles and sexual politics in the Soviet Union, with the new government initially promoting women's liberation and more liberal attitudes toward sexuality, though these would be reversed under Stalin. The film's exploration of these themes reflects the social tensions and debates of this transitional period in Soviet history.

Why This Film Matters

Bed and Sofa stands as a landmark in both Soviet and world cinema for its progressive treatment of themes that were considered taboo in the 1920s. The film's frank exploration of sexuality, infidelity, and women's autonomy was decades ahead of its time, particularly in its conclusion where the female protagonist chooses independence over compromising with either man. It represents a rare example of Soviet cinema that dealt with personal relationships and domestic life rather than revolutionary epics or propaganda. The film influenced generations of filmmakers interested in realistic depictions of relationships and living conditions. Its preservation and restoration have allowed modern audiences to appreciate its sophisticated approach to narrative and character development. The film is now recognized as a pioneering work in feminist cinema, with Lyuda's decision to leave both men seen as an early example of female agency in film.

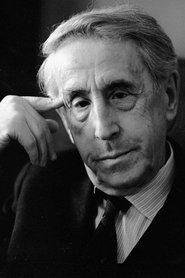

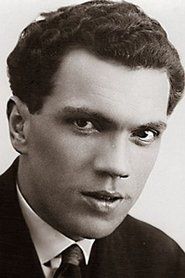

Making Of

The production faced significant challenges from Soviet censorship authorities due to its controversial themes. Director Abram Room had to defend the film's artistic merit and social commentary against accusations of bourgeois decadence. The casting was particularly important - Nikolai Batalov (Kolya) was already a established star, while Lyudmila Semyonova (Lyuda) was relatively new to film but brought a remarkable naturalism to her performance. Vladimir Fogel (Volodya), known for his comic roles, brought a subtle complexity to what could have been a straightforward antagonist. The cramped apartment set was so realistic that many viewers believed it was an actual Moscow apartment. The film's editing style, influenced by Soviet montage theory, was innovative in its use of quick cuts to build tension during confrontations. The production team worked closely with housing experts to accurately depict the living conditions of working-class Moscow residents during the NEP period.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Grigory Giber was innovative in its use of close-ups to convey psychological states and its mobile camera work within the confined apartment space. The film employs sophisticated techniques including deep focus within the cramped set to show multiple characters' reactions simultaneously. The camera often adopts subjective viewpoints, particularly during scenes of tension between the three main characters. The use of mirrors and reflections throughout the film creates visual metaphors for the characters' divided loyalties and self-reflection. The lighting design emphasizes the claustrophobic nature of the apartment, with shadows used to create psychological tension. The film's visual style balances Soviet montage influences with more subtle, psychological approaches to filmmaking that would become more common in the 1930s.

Innovations

The film was notable for its innovative use of montage to convey psychological tension and its sophisticated approach to narrative structure within the constraints of silent cinema. The production design created a remarkably realistic and detailed apartment set that became a character in itself. The film's editing techniques, particularly during the confrontation scenes, influenced later psychological dramas. The use of location shooting in Moscow streets added authenticity rarely seen in Soviet studio productions of the era. The film's preservation represents a technical achievement in itself, with restorers working from multiple incomplete prints to reconstruct the most complete version possible.

Music

As a silent film, Bed and Sofa would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The exact compositions used are not documented, but theaters typically used classical pieces or specially compiled scores. Modern restorations have featured new musical scores, including a notable composition by Michael Nyman for the 1990s restoration. The 2005 Criterion Collection release included a score by Robert Israel that incorporated Russian folk melodies and period-appropriate classical music. The film's rhythmic editing and visual pacing suggest it was designed to work with musical accompaniment that could enhance its emotional and dramatic moments.

Famous Quotes

"There's room for three in this apartment, but only two in this bed" (intertitle)

"I won't be a burden to either of you" (Lyuda's final intertitle)

A sofa is not a home" (Volodya's intertitle)

Friendship is tested by proximity" (Kolya's intertitle)

Memorable Scenes

- The tense dinner scene where the three characters navigate their changing relationships while eating in the cramped space

- The bathroom scene where Lyuda's vulnerability and the men's reactions create palpable tension

- The final confrontation where both men must confront their roles in the situation

- Lyuda's decision to leave both men, a remarkably feminist moment for 1920s cinema

- The opening shots establishing the claustrophobic apartment setting

Did You Know?

- The film's Russian title 'Tretya Meshchanskaya' translates to 'The Third Meshchanskaya,' referring to the street address where the apartment was located, not a third person as commonly misunderstood

- Considered extremely controversial for its time due to its frank depiction of sexuality and suggestion of a ménage à trois

- The film was banned in several countries including the United Kingdom and United States for decades

- Director Abram Room was only 27 years old when he made this groundbreaking film

- The film was nearly lost but was preserved and restored by the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia

- It was one of the first Soviet films to deal openly with themes of sexual freedom and women's independence

- The bathroom scene was particularly scandalous as it showed Lyuda in a state of undress, unheard of in cinema of the era

- The film's international success was unusual for a Soviet production of the 1920s

- Screenwriter Viktor Shklovsky was a prominent formalist critic and theorist

- The film's release coincided with the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revolution

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics were divided, with some praising the film's realism and social commentary while others criticized its bourgeois focus on personal relationships rather than class struggle. International critics were generally more enthusiastic, with Variety calling it 'a daring and sophisticated piece of cinema' and British film journal Close Up praising its psychological depth. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a masterpiece, with The Guardian listing it among the greatest silent films ever made. The Criterion Collection release included essays highlighting the film's formal innovations and social significance. Film scholar Jay Leyda described it as 'one of the most sophisticated Soviet films of the 1920s.' The film's reputation has grown significantly since its rediscovery in the West during the 1960s, with many contemporary critics noting how remarkably modern its attitudes toward relationships and gender politics remain.

What Audiences Thought

Initial Soviet audience reception was mixed, with some viewers shocked by the film's frank treatment of sexuality while others appreciated its realistic depiction of Moscow life. The film generated significant discussion in Soviet newspapers and magazines about its social implications. In international markets, where it was eventually shown, audiences were often surprised by the sophistication of Soviet cinema beyond the political epics they expected. Modern audiences at film festivals and revival screenings have responded enthusiastically to the film's psychological complexity and surprisingly contemporary themes. The film's availability on home video and streaming platforms has introduced it to new generations of viewers, who often comment on how relevant its exploration of relationships and living conditions remains today.

Awards & Recognition

- Named one of the 100 most important films of world cinema by the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF)

- Recognized as a milestone of Soviet cinema by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- Soviet montage theory

- Psychological realist literature

- Fyodor Dostoevsky's psychological novels

- Contemporary Soviet plays about urban life

This Film Influenced

- L'Age d'Or (1930)

- The Rules of the Game (1939)

- Jules and Jim (1962)

- The Last Picture Show (1971)

- Husbands and Wives (1992)

- Y Tu Mamá También (2001)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered partially lost for decades but has been restored by the Gosfilmofond Russian State Archive. The most complete version runs 78 minutes, though some scenes may still be missing. The restoration work involved combining elements from multiple prints found in various archives. The Criterion Collection released a restored version on DVD and Blu-ray in 2005. The film is now preserved in several major film archives including the Museum of Modern Art and the British Film Institute.