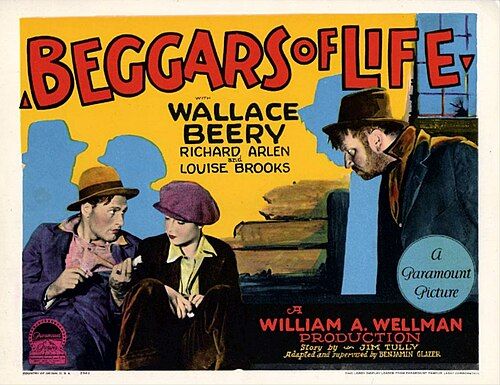

Beggars of Life

"A Girl Who Dared to Live Beyond the Law!"

Plot

After accidentally killing her abusive stepfather in self-defense, young Nancy (Louise Brooks) flees her rural home with Jim (Richard Arlen), a drifter who discovers her hiding. To protect her identity and avoid detection, Nancy disguises herself as a boy, and together they embark on a desperate journey to Canada by hopping freight trains. Their path is fraught with danger as they encounter a hostile community of hobos, led by the menacing Oklahoma Red (Wallace Beery), who initially threatens them but eventually becomes an unlikely ally. The trio faces numerous challenges including police pursuit, harsh weather, and internal conflicts, culminating in a dramatic car theft and border crossing attempt. The film explores themes of survival, redemption, and the formation of makeshift families among society's outcasts, all set against the backdrop of Depression-era America.

About the Production

Beggars of Life was one of Paramount's first part-talkie films, featuring synchronized sound effects and some dialogue sequences. The production faced significant challenges filming on location in harsh weather conditions, particularly during the mountain sequences. Director William A. Wellman insisted on using real freight trains and authentic hobo camps to achieve realism. The film's controversial subject matter of a young woman on the run with male companions required careful handling to satisfy the Hays Code censors of the era.

Historical Background

Beggars of Life was produced during a pivotal moment in cinema history - the transition from silent films to talkies. Released in 1928, just before the full impact of the Great Depression, the film captured the growing anxiety about economic instability and homelessness in America. The late 1920s saw a rise in films dealing with social issues, as audiences became more interested in stories reflecting real-world struggles. The film's release coincided with the implementation of the Hays Code, which was beginning to enforce stricter moral standards in Hollywood productions. This period also saw the rise of the 'part-talkie' format, as studios experimented with incorporating sound into their productions. The film's portrayal of hobos and drifters resonated with audiences who were increasingly concerned about the economic future, foreshadowing the widespread poverty that would soon grip the nation during the Depression.

Why This Film Matters

Beggars of Life holds significant cultural importance as one of the earliest films to realistically portray America's underclass. The film broke new ground in its sympathetic depiction of hobos and drifters, humanizing characters who were typically marginalized in cinema and society. Louise Brooks' performance as a strong, independent female character who disguises herself as a boy challenged traditional gender roles and became an iconic representation of female empowerment in silent cinema. The film's influence can be seen in later road movies and films about societal outcasts. It also marked an important step in the transition to sound cinema, demonstrating how visual storytelling could be enhanced rather than replaced by new technology. The movie's gritty realism and location shooting influenced the documentary-style filmmaking that would become more prevalent in the 1930s. Additionally, the film helped establish the archetype of the misunderstood anti-hero in American cinema.

Making Of

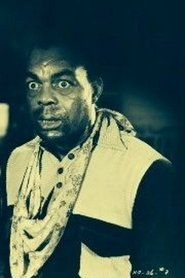

The production of Beggars of Life was marked by William A. Wellman's commitment to authenticity. Having been a hobo himself as a teenager, Wellman insisted on filming in real locations and using actual freight trains. The cast and crew endured harsh conditions while shooting in the Sierra Nevada mountains, with temperatures often dropping below freezing. Louise Brooks, initially considered difficult to work with, impressed Wellman with her professionalism during the demanding location shoots. The film's transition to sound technology during production created additional challenges, with some scenes needing to be reshot to accommodate the new sound equipment. The casting of Wallace Beery as Oklahoma Red was a stroke of genius, as the actor's gruff demeanor and naturalistic style perfectly embodied the character. The film's realistic depiction of hobo life caused controversy with studio executives who feared it might glorify vagrancy, but Wellman stood his ground, arguing that the film was ultimately about redemption and the human spirit.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Henry W. Gerrard was groundbreaking for its time, featuring extensive location shooting that brought unprecedented realism to the screen. Gerrard employed natural lighting techniques in the outdoor sequences, particularly during the train-hopping scenes, creating a documentary-like quality that enhanced the film's authenticity. The camera work during the action sequences was innovative for its era, with dynamic tracking shots following the moving trains and handheld-style photography during chase scenes. The visual contrast between the open expanses of the American landscape and the claustrophobic confines of boxcars and hobo camps created a powerful visual metaphor for freedom and entrapment. The film's use of shadow and light in the night scenes was particularly effective in creating mood and tension. The cinematography successfully captured both the beauty and harshness of the American wilderness, reinforcing the film's themes of survival against overwhelming odds.

Innovations

Beggars of Life was technically innovative in several ways. As one of Paramount's first part-talkies, it pioneered techniques for blending synchronized sound with traditional silent film storytelling. The film's extensive location shooting using actual moving freight trains represented a significant technical achievement, requiring custom camera mounts and safety equipment. The production developed new methods for recording sound in outdoor environments, overcoming the limitations of early sound recording equipment. The film also featured innovative stunt work and action sequences that pushed the boundaries of what was considered possible in cinema of the era. The special effects used to create the illusion of train movement and weather conditions were particularly sophisticated for the time. The film's successful integration of sound and visual elements influenced the development of hybrid film techniques during the industry's transition to full sound production.

Music

As a part-talkie, Beggars of Life featured a synchronized musical score composed by Josiah Zuro, along with carefully crafted sound effects and limited dialogue sequences. The musical score incorporated popular folk melodies of the era, including traditional hobo songs that added cultural authenticity to the proceedings. The sound effects were particularly innovative for the time, with realistic train noises, weather effects, and ambient sounds that enhanced the immersive quality of the film. The dialogue sequences, while limited, were strategically placed to emphasize key emotional moments without disrupting the primarily visual storytelling. The film's soundtrack demonstrated how sound could enhance rather than replace silent film techniques, serving as a model for other transitional films of the period. The musical themes helped establish the emotional tone of different scenes, with jaunty rhythms accompanying moments of freedom and somber melodies underscoring periods of hardship.

Famous Quotes

"A man's got to do what he's got to do, even if it kills him." - Oklahoma Red

"We're all beggars in this life, some just admit it sooner than others." - Jim

"You can't run away from yourself, no matter how fast the train goes." - Nancy

"The road doesn't care who you are, only where you're going." - Jim

"In this world, you're either the hunter or the hunted. Choose wisely." - Oklahoma Red

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Nancy kills her stepfather in self-defense, establishing the film's moral ambiguity

- The tense moment when Nancy first disguises herself as a boy, cutting her hair and binding her chest

- The spectacular train-hopping sequence with the actors performing their own stunts on moving freight cars

- The dramatic confrontation in the hobo camp where Oklahoma Red initially threatens Jim and Nancy

- The car theft scene that showcases the trio's desperation and resourcefulness

- The final border crossing attempt, filled with tension and uncertainty about their fate

Did You Know?

- This was Louise Brooks' first major starring role for Paramount Pictures and helped establish her as a major star.

- The film was one of the first 'part-talkies' - it had a synchronized musical score and sound effects, plus some dialogue sequences.

- Wallace Beery's performance as Oklahoma Red was so convincing that real hobos who visited the set thought he was one of them.

- Director William A. Wellman drew from his own experience as a real hobo in his youth to bring authenticity to the film.

- The train sequences were filmed using actual moving freight trains, with the actors performing their own stunts.

- The film was based on Jim Tully's autobiographical novel, which was considered quite controversial for its time.

- Louise Brooks' iconic bob haircut became a fashion trend after women saw it in this film.

- The movie was banned in several cities due to its depiction of violence and its sympathetic portrayal of criminals.

- Richard Arlen and Louise Brooks began a real-life romance during filming that lasted for several years.

- The hobo camp scenes featured actual homeless people as extras to add authenticity.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Beggars of Life for its raw realism and powerful performances. The New York Times hailed it as 'a gripping drama of life on the road' and particularly singled out Wallace Beery's performance as 'extraordinary in its authenticity.' Variety noted the film's 'unflinching look at the darker side of American life' while also praising its 'moments of genuine humanity.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a masterpiece of late silent cinema, with many considering it one of William A. Wellman's finest works. The film is now recognized for its sophisticated visual storytelling and its role in launching Louise Brooks to stardom. Critics have also noted how effectively the film blends elements of adventure, romance, and social commentary, creating a work that transcends simple genre categorization. The part-talkie sequences have been praised for their innovative use of sound to enhance rather than dominate the visual narrative.

What Audiences Thought

Beggars of Life was a commercial success upon its release, resonating strongly with audiences who were drawn to its authentic portrayal of life on the margins of society. The film's action sequences and romantic elements appealed to mainstream moviegoers, while its social themes gave it depth that distinguished it from typical adventure films of the era. Audience reaction to Louise Brooks was particularly enthusiastic, with many viewers writing fan letters praising her performance and distinctive style. The film's depiction of hobo life struck a chord with Americans during a time of growing economic uncertainty, though some audience members found certain scenes too intense for the period. The film's popularity helped establish the 'road movie' as a viable genre and influenced public perception of homeless Americans, generating some sympathy for their plight. Despite being banned in several conservative markets, the film found widespread acceptance in most urban centers and continued to draw audiences even as fully sound films began to dominate theaters.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were recorded for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Jim Tully's autobiographical novel

- German Expressionist cinema

- American social realist literature

- Contemporary newspaper stories about hobos

- Wellman's personal experiences as a drifter

This Film Influenced

- The Grapes of Wrath (1940)

- Sullivan's Travels (1941)

- They Live by Night (1948)

- Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

- Thelma & Louise (1991)

- Into the Wild (2007)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Beggars of Life has been preserved by the Library of Congress and selected for the National Film Registry in 2020 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. The film exists in both its silent and part-talkie versions, with the sound version being more complete. A restoration was completed in 2019 by The Museum of Modern Art in conjunction with Paramount Pictures, which included reconstruction of missing scenes and enhancement of the existing sound elements. The restored version premiered at the Cannes Film Festival as part of their Classics section. The film is considered well-preserved compared to many other silent films of the era, with no lost footage and relatively good image quality throughout.