Call of the Cuckoo

Plot

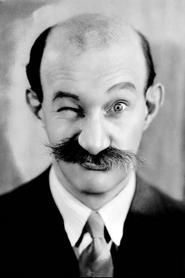

Max Davidson plays Abe Shrimplinsky, a Jewish immigrant who has finally saved enough money to buy his dream house for his family. The celebration turns to horror when he discovers his new home is located directly next to an insane asylum, where patients constantly escape and create chaos. Throughout the day, Abe must deal with escaped lunatics invading his home, destroying his new furniture, and terrorizing his family during their housewarming party. The film culminates in a frantic climax where Abe must defend his home and family from a full-scale asylum break-out, leading to increasingly absurd and comedic situations.

About the Production

This was one of several shorts that Hal Roach produced starring Max Davidson, capitalizing on his popularity as a Jewish character actor. The film was part of Roach's successful series of comedy shorts that also included Laurel & Hardy and Charley Chase. The asylum setting allowed for elaborate physical comedy gags and surreal situations that were becoming increasingly popular in late silent era comedies.

Historical Background

1927 was a pivotal year in cinema history, representing the peak of the silent era just before the transition to sound. The film industry was experiencing enormous creative output, with comedy shorts being particularly popular with audiences. Hal Roach Studios was at the height of its powers, producing successful comedy series featuring stars like Harold Lloyd, Laurel & Hardy, and character actors like Max Davidson. This period also saw increasing sophistication in film comedy, with more elaborate production values and complex gag structures. The year 1927 would see the release of The Jazz Singer in October, forever changing the industry and making films like Call of the Cuckoo representative of the final flowering of pure silent comedy.

Why This Film Matters

Call of the Cuckoo represents the type of ethnic humor that was common in 1920s American cinema, particularly in comedy shorts. Max Davidson's films were popular with both Jewish and non-Jewish audiences of the era, though the stereotypical portrayals would be considered problematic today. The film also exemplifies the 'home invasion' comedy genre that was popular in silent films, where domestic tranquility is disrupted by chaotic forces. As part of the Hal Roach comedy legacy, it contributes to our understanding of how the studio developed its comedy style and influenced later generations of comedians. The film's survival allows modern audiences to study the evolution of screen comedy and the transition from broad slapstick to more character-driven humor.

Making Of

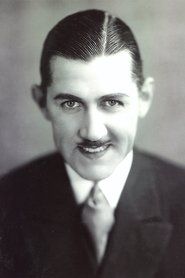

Director Clyde Bruckman was a highly respected comedy director who had worked with Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd before joining Hal Roach Studios. Bruckman was known for his meticulous planning of gags and his ability to extract maximum comedic value from simple situations. The production utilized many of Roach's stock company actors, including Spec O'Donnell, who frequently played juvenile roles in the studio's comedies. The asylum setting allowed for creative freedom in staging increasingly absurd situations, with escaped patients providing a constant stream of comic interruptions. The film was shot quickly, as was typical for short comedies of the era, with most scenes completed in one or two takes to maintain freshness and spontaneity in the performances.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Art Lloyd (no relation to Harold) utilized the standard techniques of silent comedy, including wide shots to capture physical gags and medium shots for character reactions. The camera work was functional rather than artistic, prioritizing clarity of action over visual style. The film made effective use of the limited sets, particularly the house and asylum grounds, creating visual contrasts between domestic order and asylum chaos. Lighting was typical of studio productions of the era, bright and even to ensure visibility of the performers' expressions and movements. The cinematography supported the comedy by maintaining clear sightlines for gags and allowing audiences to follow the increasingly complex physical comedy sequences.

Innovations

While not technically innovative, the film demonstrated the sophisticated gag construction that had become standard in late silent comedies. The production made effective use of editing rhythm to build comedic momentum, particularly in sequences involving multiple characters and simultaneous action. The film showcased the advanced state of studio comedy production by 1927, with well-designed sets that could accommodate complex physical comedy. The asylum setting allowed for creative use of props and set pieces to generate laughs, demonstrating how comedy filmmakers had learned to maximize production value within the constraints of short-form storytelling.

Music

As a silent film, Call of the Cuckoo would have been accompanied by live music during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have included a theater organist or small orchestra playing popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and specially composed mood music. The asylum scenes would likely have been accompanied by quirky or mysterious music to enhance the comedic effect, while domestic scenes would have featured lighter, more romantic themes. No original score was composed specifically for the film, as was common for short comedies of the period. Modern screenings often feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate compiled music.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue quotes available)

Memorable Scenes

- The chaotic housewarming party where escaped asylum patients repeatedly invade and disrupt the celebration, with Abe desperately trying to maintain order while his guests flee in terror. The scene escalates as more patients arrive, each bringing their own brand of madness to the domestic setting, culminating in a frantic chase through the house and yard.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the last films directed by Clyde Bruckman before his alcoholism began severely affecting his career in the late 1920s.

- Max Davidson was one of the few actors of the era who specialized in playing Jewish characters, though his portrayals would be considered stereotypical by modern standards.

- The film features an early appearance by Stan Laurel, though in a minor role before his famous partnership with Oliver Hardy was fully established.

- The asylum scenes were filmed on the same sets used for other Hal Roach productions, demonstrating the studio's efficient use of resources.

- This short was part of a popular series of 'family man in peril' comedies that Hal Roach produced in the mid-to-late 1920s.

- The film's title is a play on the phrase 'call of the wild,' substituting 'cuckoo' to reference both the asylum and the madness of the situation.

- Like many silent comedies, the film featured minimal intertitles, relying heavily on visual gags and physical comedy.

- The film was released just months before the debut of The Jazz Singer, which would soon revolutionize the film industry with sound.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews praised the film for its energetic pacing and Davidson's comedic performance, with Variety noting the film's 'laugh-provoking situations' and effective use of the asylum premise. Modern critics and film historians view the film as a solid example of late silent-era comedy shorts, appreciating its efficient gag construction and Davidson's expressive performance. While not as celebrated as the work of Chaplin, Keaton, or Lloyd, the film is recognized as an important part of Max Davidson's body of work and the Hal Roach comedy output. The film is often cited in discussions of ethnic representation in early Hollywood cinema, providing insight into how different cultures were portrayed for mainstream audiences.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by contemporary audiences, who enjoyed Davidson's relatable everyman character and the increasingly absurd situations he encountered. Moviegoers of the era appreciated the film's fast pace and constant stream of visual gags, which were hallmarks of successful comedy shorts. The asylum setting provided a familiar comedy premise that audiences immediately understood and enjoyed. While not as memorable as the era's biggest comedy hits, the film satisfied audiences looking for light entertainment during their theater visits. Modern audiences who discover the film through revival screenings or home video often find it fascinating as a time capsule of 1920s comedy sensibilities and cultural attitudes.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The General (1926) - for its escalating disaster comedy

- The Kid (1921) - for its focus on family protection

- Harold Lloyd films - for their everyman in crisis approach

This Film Influenced

- Later Hal Roach comedy shorts

- The Three Stooges shorts with similar premises

- Abbott and Costello routines involving home disasters

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form and has been preserved by film archives. Prints are held at major film institutions including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The film has been made available through various home video releases and streaming services specializing in classic cinema.