Camille

"The Greatest Love Story of All Time"

Plot

Marguerite Gautier, known as Camille, is a beautiful Parisian courtesan who lives a life of luxury and superficial relationships until she meets Armand Duval, a sincere young man from a respectable family. Their passionate romance flourishes until Armand's father confronts Camille, begging her to leave his son to protect the family's reputation and Armand's future prospects. Heartbroken but selfless, Camille agrees to sacrifice her love and returns to her former life, leading Armand to believe she has abandoned him for wealth. As Camille's health deteriorates from tuberculosis and she falls into poverty, Armand discovers the truth of her sacrifice and rushes to her side, arriving just moments before her death to reconcile their tragic love story.

About the Production

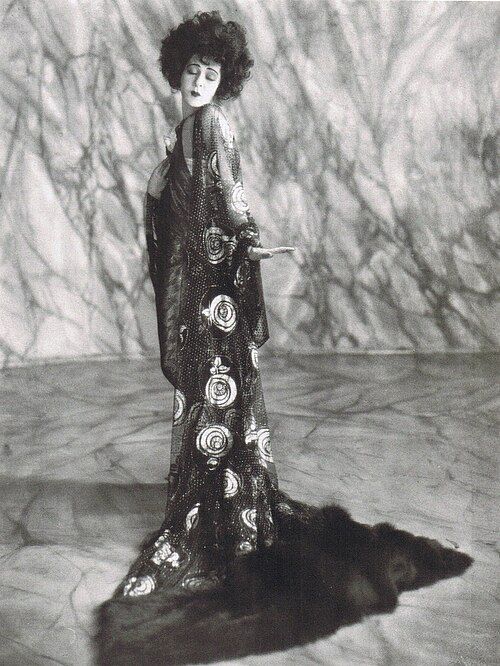

The film featured highly stylized Art Nouveau sets and costumes designed by Natasha Rambova, who would later become Valentino's wife. Nazimova exercised significant creative control as both star and producer, insisting on an artistic, avant-garde approach rather than realistic settings. The production was notable for its elaborate visual design that emphasized the artificiality of Camille's world through geometric patterns, flowing fabrics, and symbolic props.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the golden age of silent cinema in 1921, a pivotal year when Hollywood was establishing itself as the global center of film production. This period saw the rise of the star system, with actors like Valentino becoming cultural icons whose personal lives were as fascinating to audiences as their films. The adaptation of classic literature was considered a way to lend cultural legitimacy to the relatively new medium of cinema, and 'Camille' was part of this trend of elevating film through literary associations. The film emerged just before the Roaring Twenties would fully transform American culture, reflecting the transitional nature of the era with its themes of traditional morality versus personal freedom.

Why This Film Matters

This adaptation of 'Camille' represents an important moment in cinema history as an example of how silent films could handle complex emotional narratives and literary themes. Nazimova's dual role as star and producer demonstrated the significant creative power women could wield in early Hollywood, before the studio system would later marginalize female voices. The film's avant-garde visual design influenced subsequent approaches to artistic filmmaking, showing that cinema could be more than mere entertainment. The story itself, with its themes of sacrifice and social hypocrisy, resonated with audiences navigating the changing moral landscape of post-World War I America. Valentino's performance helped establish the romantic leading man archetype that would dominate Hollywood for decades.

Making Of

The production was marked by Nazimova's artistic vision and insistence on creative control. She worked closely with Natasha Rambova to create a highly stylized visual world that emphasized the artificial nature of Camille's existence through elaborate sets featuring flowing curtains, geometric patterns, and symbolic props. Valentino, still building his reputation, brought his signature intensity to the role of Armand, though his relationship with Nazimova on set was reportedly strained due to their both being strong-willed artists. The film was shot during the summer of 1921 at Nazimova's personal studio, where she could maintain complete control over the artistic direction. The production team used innovative lighting techniques to create the contrast between the glittering surface of Parisian society and the emotional truth beneath, with cinematographer Tony Gaudio employing dramatic shadows and soft focus to enhance the romantic atmosphere.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Tony Gaudio employed innovative techniques for the time, using dramatic lighting to create emotional depth and visual poetry. Gaudio utilized soft focus lenses during romantic scenes to enhance the dreamlike quality of Camille and Armand's love, while harsher lighting emphasized the harsh realities of her life and illness. The camera work incorporated careful composition that framed characters within the elaborate Art Nouveau sets, using architectural elements to reinforce themes of confinement and artificiality. The cinematography also made effective use of shadows and light to create visual metaphors for the story's themes of truth versus appearance, with Camille often shown in partial shadow to represent her hidden true self.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical innovation, the film was notable for its advanced approach to visual storytelling through stylized production design. The Art Nouveau aesthetic represented an ambitious artistic vision that went beyond the more realistic style common in films of the period. The production team experimented with color tinting for emotional effect, using amber tones for romantic scenes and blue tints for melancholy moments. The elaborate sets were designed with mobility in mind, allowing for complex camera movements that enhanced the visual storytelling. The film also demonstrated sophisticated use of intertitles to convey narrative information while maintaining dramatic momentum.

Music

As a silent film, 'Camille' would have been accompanied by live musical performances in theaters, with scores typically compiled from classical pieces and original compositions. The music would have been particularly crucial during emotional scenes, with romantic themes likely drawing from composers like Chopin and Debussy to enhance the Parisian setting. The deathbed scene would have been accompanied by somber, dramatic music to amplify the tragedy. Larger theaters might have employed full orchestras, while smaller venues used piano or organ accompaniment. The score would have been carefully synchronized with the film's emotional beats, using leitmotifs for characters and themes to enhance narrative comprehension without dialogue.

Famous Quotes

Love is the only reality that matters

I would rather die than be the cause of your ruin

In sacrificing my happiness, I have saved your future

Society forgives the sin but never the scandal

True love knows no sacrifice too great

Memorable Scenes

- Camille and Armand's passionate declaration of love in her Parisian apartment, surrounded by elaborate Art Nouveau decor

- The tense confrontation between Camille and Armand's father, where she agrees to sacrifice their love

- Camille's return to her former life of luxury, her face a mask of indifference hiding her broken heart

- The deathbed scene where Armand finally learns the truth and reconciles with the dying Camille

- The opening salon scene introducing Camille's world of artificial beauty and superficial relationships

Did You Know?

- This was one of Rudolph Valentino's final films before his breakthrough superstardom in 'The Sheik' (1921), which was released just weeks later

- Alla Nazimova was not only the star but also had her own production company, making her one of the most powerful women in Hollywood at the time

- Natasha Rambova worked on costume design and art direction before marrying Valentino the following year

- The film's Art Nouveau aesthetic was considered highly avant-garde and ahead of its time, influencing later art deco designs in cinema

- Rex Cherryman, who played Gaston, died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1928 at age 31, making this one of his few surviving film performances

- This was one of at least seven film adaptations of Alexandre Dumas' novel 'La Dame aux Camélias' made during the silent era

- Nazimova was known for her intense method acting style, reportedly staying in character throughout the entire production

- The film's sets were designed to be deliberately artificial and theatrical, rejecting the trend toward realism in filmmaking

- Contemporary reports indicated that Nazimova and Valentino had a tense working relationship due to their strong artistic temperaments

- The film's intertitles were written by prominent screenwriter Mary H. O'Connor, who specialized in literary adaptations

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics generally praised Nazimova's performance and the film's artistic ambitions, with Variety noting her 'intense and moving portrayal' of the tragic heroine. The New York Times highlighted the film's 'artistic merits' while some reviewers found the stylized approach excessive for the emotional story. Film publications like Photoplay and Motion Picture Magazine gave positive reviews, particularly praising the chemistry between the leads. Modern film historians view the work as an important example of silent-era artistic experimentation, though some criticize the excessive artifice as potentially distracting from the emotional core. The film is now studied for its place in both Nazimova's and Valentino's careers and as an example of literary adaptation in early cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The film was moderately successful with audiences, particularly attracting viewers who appreciated literary adaptations and romantic melodramas. Valentino's growing popularity helped draw crowds, though his superstardom would explode later that year with 'The Sheik.' Audiences of the time responded strongly to the tragic romance and themes of selfless love, which resonated with the sentimental sensibilities of early 1920s moviegoers. The film's artistic design was noted and discussed by cinema enthusiasts, though mainstream audiences were more focused on the emotional story and the star power of the leads.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Alexandre Dumas, fils' novel 'La Dame aux Camélias' (1852)

- Verdi's opera 'La Traviata' (1853)

- Previous stage and film adaptations of the story

- Art Nouveau movement

- Theatrical acting traditions

- German Expressionist cinema

This Film Influenced

- 'Camille' (1936) starring Greta Garbo

- Subsequent romantic melodramas of the 1920s

- Later adaptations of classic literature in Hollywood

- Art deco influenced films of the late 1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Lost film - no complete copies are known to survive. Like approximately 75% of silent films, this version of 'Camille' has been lost to time, though some still photographs and production stills exist in various film archives.