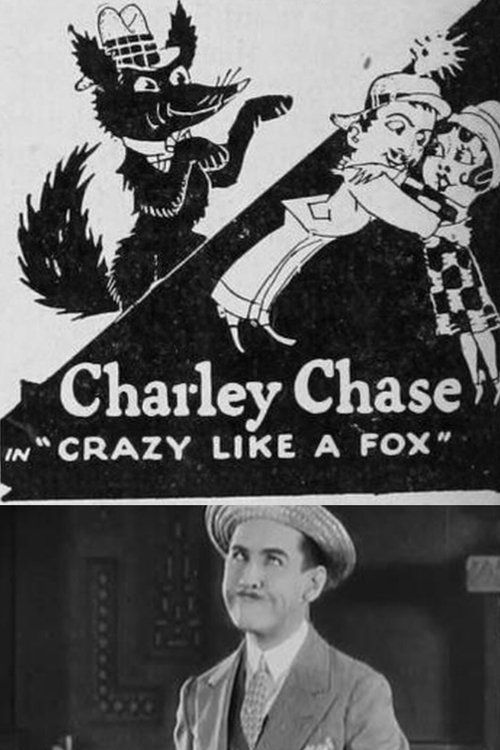

Crazy Like a Fox

Plot

In this classic silent comedy, wealthy capitalists Cyrus (William V. Mong) and Mr. Wharton arrange for their children to marry each other to merge their business interests. However, their offspring have no interest in this arranged marriage. The young woman (Martha Sleeper) attempts to run away from home and heads to the train station, where she encounters a young man (Charley Chase) who is also trying to escape an unwanted arranged marriage. The two immediately fall for each other, completely unaware that they are the very people their parents want to force together. Both independently decide they must sabotage their parents' marriage plans, leading to a series of hilarious misunderstandings and comedic situations as they unwittingly work against their own interests while falling deeper in love.

About the Production

This was one of the early directorial efforts by Leo McCarey, who would later become one of Hollywood's most respected directors. The film was produced during the peak of the silent comedy era at Hal Roach Studios, known as 'The Lot of Fun.' McCarey utilized Charley Chase's unique comedic style, which relied more on situational comedy and character-driven humor rather than the slapstick gags common in the era. The production faced the typical challenges of silent filmmaking, including the need for exaggerated physical performances and clear visual storytelling without dialogue.

Historical Background

The year 1926 was a pivotal time in American cinema, as the silent film era was reaching its artistic peak while the transition to sound was beginning to loom on the horizon. Hollywood was firmly established as the center of global film production, with studios like Hal Roach becoming major players in the industry. The Roach studio, in particular, had perfected the art of the short comedy, producing a steady stream of two-reelers that entertained audiences before feature presentations. This was also a period of significant social change in America, with the Jazz Age bringing new attitudes about youth, romance, and rebellion against tradition. The film's theme of young people resisting arranged marriage reflected these changing mores. The economic prosperity of the mid-1920s meant that movie-going had become America's favorite pastime, with theaters showing multiple programs daily. Comedy shorts like 'Crazy Like a Fox' were essential components of these programs, providing the light entertainment that audiences craved.

Why This Film Matters

While not as well-remembered today as the works of Chaplin or Keaton, 'Crazy Like a Fox' represents an important example of the sophisticated character-driven comedy that Hal Roach Studios was producing in the mid-1920s. The film showcases Charley Chase's unique comedic style, which influenced later comedians with its blend of relatable situations and subtle humor. Leo McCarey's early directorial work on this and other Chase shorts laid the groundwork for his later success as one of Hollywood's most respected directors of comedy and drama. The film also exemplifies the two-reel comedy format that dominated American movie theaters before the advent of television. Its preservation by the Academy Film Archive ensures that this example of 1920s comedy craftsmanship remains available for study and appreciation by future generations. The movie's title has entered the American lexicon as an idiom, demonstrating how deeply film culture permeated everyday language during the golden age of Hollywood.

Making Of

Leo McCarey, who had previously worked as a writer and gag man for Hal Roach, was given the opportunity to direct this Charley Chase short as part of his development as a filmmaker. McCarey's approach to comedy was more sophisticated than many of his contemporaries, focusing on character development and realistic situations rather than pure slapstick. Charley Chase, whose real name was Charles Parrott, was deeply involved in the creative process of his films, often contributing to the screenplay and gags. The production utilized the efficient assembly-line system developed by Hal Roach, which allowed for the production of high-quality shorts on tight schedules. The film was shot on the Hal Roach studio lot, with the train station scenes likely filmed on a constructed set. The chemistry between Chase and Martha Sleeper was genuine, as both were experienced comedy performers who understood the timing and subtlety required for silent comedy. McCarey's direction showed early signs of the humanistic touch that would characterize his later, more celebrated works.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Crazy Like a Fox' was typical of Hal Roach Studios' productions of the mid-1920s, featuring clear, well-composed shots that effectively served the comedy without calling attention to themselves. The film likely utilized the standard cameras and film stock of the period, with careful attention to lighting to ensure clarity in the medium shots and close-ups that were crucial for silent comedy performance. The train station sequences demonstrate the cinematographer's ability to handle more complex set pieces, using depth and movement to enhance the physical comedy. The visual style prioritized clarity over artistic flourishes, as was common for comedy shorts of the era, ensuring that audiences could easily follow the gags and plot developments. The camera work supported Charley Chase's performance by allowing enough space for his physical comedy while also capturing the subtle facial expressions that were essential to his character-driven humor.

Innovations

While 'Crazy Like a Fox' was not a groundbreaking film in terms of technical innovation, it demonstrated the high level of craftsmanship that Hal Roach Studios had achieved by the mid-1920s. The film effectively utilized the technical limitations of the era to create a polished comedy short. The editing was particularly noteworthy for its rhythm and timing, essential elements for comedy that McCarey would perfect in his later career. The film's use of location-style sets, particularly the train station, showed the studio's ability to create convincing environments on a modest budget. The makeup and costume design effectively established character types and social status without dialogue. The film's preservation has allowed modern audiences to appreciate the technical quality of 1920s film stock and the clarity of images that could be achieved even in routine studio productions. While not revolutionary, the film represents the solid technical foundation that made American comedy shorts of this period so successful.

Music

As a silent film, 'Crazy Like a Fox' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment for a comedy short of this type would have been a piano or small ensemble, playing popular songs of the era along with specially composed or improvised music that matched the on-screen action. The score would have emphasized the comedic moments with playful, upbeat music and provided romantic themes during the love scenes. No original score or specific musical cues for this film survive, as was common with silent films where the music was created anew for each screening. Modern screenings of the film typically use period-appropriate compiled scores or newly composed music that captures the spirit of 1920s comedy accompaniment. The lack of recorded sound meant that the film's success depended entirely on its visual storytelling, which it accomplished effectively through the performances and McCarey's direction.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue quotes available)

Memorable Scenes

- The train station encounter where the two protagonists meet and fall in love without knowing each other's identities, featuring Charley Chase's trademark blend of physical comedy and subtle romantic gestures

- The scene where both characters independently decide to sabotage their parents' arranged marriage plans, creating dramatic irony as they work against their own interests

- The climactic revelation scene where the true identities are revealed, leading to the resolution of all misunderstandings

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films Leo McCarey directed, launching a legendary career that would include classics like 'The Awful Truth' and 'Going My Way.'

- Charley Chase was one of the most popular comedy stars of the 1920s, though his fame has been somewhat overshadowed by contemporaries like Chaplin and Keaton.

- The film was part of the Charley Chase comedy series produced by Hal Roach, which consisted of dozens of short comedies released throughout the 1920s.

- Martha Sleeper, who plays the female lead, was a prominent actress in silent films who successfully transitioned to talkies but retired from acting in 1945.

- William V. Mong, who plays one of the fathers, appeared in over 300 films between 1910 and 1950, making him one of the most prolific character actors of his era.

- The title 'Crazy Like a Fox' became a popular idiom in American English, referring to someone who appears foolish but is actually quite clever.

- The film's premise of arranged marriage and parental opposition was a common theme in 1920s comedies, reflecting the changing social attitudes toward marriage and courtship.

- The Academy Film Archive preserved this film in 2012 as part of their efforts to save important works from the silent era.

- This short was released during the height of the Jazz Age, when comedy films often reflected the era's fascination with youth rebellion against traditional values.

- The train station setting was a popular location for silent comedies, providing opportunities for physical gags and dramatic entrances/exits.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'Crazy Like a Fox' were generally positive, with trade publications like Variety and Motion Picture News praising Charley Chase's performance and the film's clever premise. Critics noted the sophistication of the humor compared to more slapstick-oriented comedies of the era. The film was particularly appreciated for its well-constructed plot and the chemistry between its leads. Modern film historians and silent comedy enthusiasts have rediscovered the film through its preservation and availability in archives, with many considering it a fine example of mid-1920s comedy craftsmanship. The film is often cited in discussions of Leo McCarey's early career and Charley Chase's contribution to American comedy. While it doesn't receive the scholarly attention given to major silent features, it's valued by specialists as representative of the high-quality short comedies that dominated American cinema screens during the silent era.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audiences in 1926 responded positively to 'Crazy Like a Fox,' as evidenced by its successful theatrical run and the continued popularity of Charley Chase shorts throughout the decade. Moviegoers of the era appreciated Chase's relatable 'everyman' character and the film's clever twist on the familiar arranged marriage trope. The film's 20-minute runtime was ideal for theater programs, providing a satisfying comedy experience without overstaying its welcome. Modern audiences who have discovered the film through archival screenings or home video releases have generally found it charming and entertaining, with many expressing surprise at the sophistication of the humor compared to their expectations of silent comedy. The film's clear visual storytelling and universal themes of romance and parental opposition have helped it remain accessible to contemporary viewers, despite being nearly a century old.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The tradition of Shakespearean comedy with mistaken identities

- Earlier silent comedy shorts by Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton

- Stage comedy traditions of mistaken identity and romantic complications

- The romantic comedy formula being developed in Hollywood

- Vaudeville comedy traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later romantic comedies featuring mistaken identity

- Subsequent Charley Chase shorts directed by McCarey

- Early sound comedies that retained silent comedy techniques

- The screwball comedies of the 1930s that McCarey would later direct

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Preserved by the Academy Film Archive in 2012. The film survives in good condition and is available for archival viewing and study. It represents one of the fortunate examples of silent comedy shorts that have survived the decades, as many films from this era have been lost due to the unstable nature of early film stock and neglect.