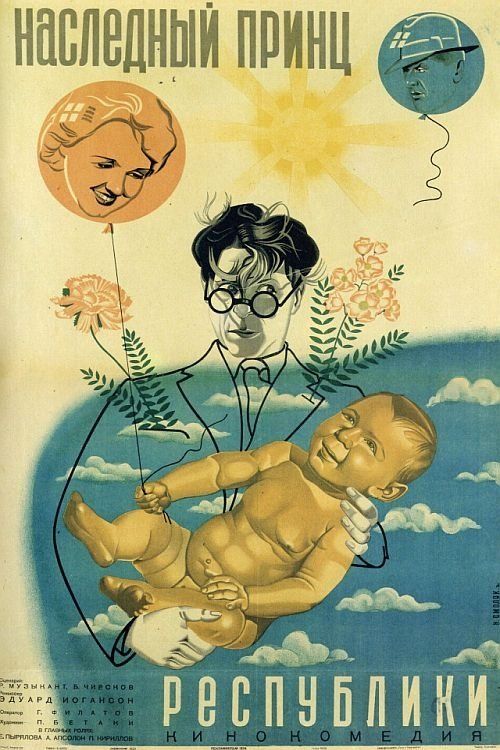

Crown Prince of the Republic

Plot

Sergei, upon learning that his wife Natasha is expecting a child, abruptly abandons her and takes up residence in a communal house filled with young, idealistic architects. The living arrangement proves chaotic as the group shares limited space while pursuing their professional ambitions. Through a series of unforeseen circumstances involving one of the tenants, Sergei unexpectedly finds himself in possession of a newborn baby. While his architect friends desperately attempt to locate the child's mother, Sergei keeps his own connection to the situation secret and actively tries to place the infant with the wrong people, creating a web of comedic complications and misunderstandings.

About the Production

This film was produced during the height of Stalin's cultural policy of Socialist Realism, which required all artistic works to be accessible to the masses and promote communist values. The communal living setting reflected the Soviet ideal of collectivism, while the comedic elements were carefully balanced with social messaging. The production faced the typical challenges of Soviet cinema in the 1930s, including limited resources and strict ideological oversight from state censors.

Historical Background

1934 was a pivotal year in Soviet history and cinema. This was the year when Socialist Realism was officially declared the only acceptable artistic style in the Soviet Union at the First Congress of Soviet Writers. The film industry was undergoing complete state centralization, with private production companies eliminated and all studios under government control. The early 1930s also saw the end of the experimental period of Soviet cinema that had produced world-renowned silent masterpieces. Films were now expected to be easily understood by the masses and serve educational and ideological purposes. The Great Purge had not yet begun in earnest, but the cultural atmosphere was becoming increasingly restrictive. The emphasis on collective living and professional dedication shown in the film reflected broader Soviet social policies of the First Five-Year Plan period.

Why This Film Matters

While not a major classic of Soviet cinema, 'Crown Prince of the Republic' represents an important transitional work between the experimental silent era and the more conventional sound films of the late 1930s. The film exemplifies how Soviet comedy adapted to the demands of Socialist Realism, incorporating social messages within entertainment. Its portrayal of communal living and professional dedication reflected and reinforced Soviet social values. The film's approach to family themes and domestic comedy influenced subsequent Soviet comedies that balanced humor with ideological content. It stands as an example of how filmmakers navigated the increasingly restrictive cultural policies of the Stalin era while attempting to maintain popular appeal.

Making Of

The making of 'Crown Prince of the Republic' took place during a transformative period in Soviet cinema. Director Eduard Ioganson, who had begun his career in the avant-garde circles of 1920s Soviet film, had to adapt to the increasingly rigid requirements of Socialist Realism. The casting process reflected the Soviet system of selecting actors who embodied both technical skill and appropriate 'type' characteristics. The communal house set was designed to reflect authentic Soviet living conditions of the era, with careful attention to period details. The production team worked under the supervision of ideological consultants who ensured the film's content aligned with communist values. The baby used in the film was reportedly the child of a crew member, as was common practice in Soviet productions of the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography by an uncredited director of photography reflects the transition from the dynamic, experimental camera work of 1920s Soviet cinema to the more conventional, narrative-focused approach of the sound era. The visual style emphasizes clarity and readability, with stable camera positioning and straightforward composition that serves the story rather than calling attention to itself. The lighting is naturalistic, particularly in the interior scenes of the communal house, creating a sense of authenticity. The film likely used standard Soviet camera equipment of the period, with limited mobility compared to Western productions of the same era.

Innovations

As an early Soviet sound film, 'Crown Prince of the Republic' represents the technical adaptation of Soviet cinema to the new sound technology. The production would have used Soviet-developed sound recording systems, which were often less sophisticated than Western equipment but functional for dialogue recording. The film demonstrates the technical challenges of recording clear dialogue in scenes with multiple characters, particularly in the crowded communal house settings. The synchronization of sound and picture, while basic by modern standards, was considered adequate for the period and reflects the state of Soviet film technology in 1934.

Music

The film features a typical Soviet sound-era score with original music composed for the production. The soundtrack would have included diegetic music within the story as well as non-diegetic underscoring to enhance emotional moments and comedic timing. The music likely incorporated elements of popular Soviet songs and folk melodies to increase accessibility for domestic audiences. As was common in Soviet films of the 1930s, the score would have been recorded live during filming or in post-production using the limited sound technology available in Soviet studios at the time.

Did You Know?

- Director Eduard Ioganson was one of the pioneering figures of Soviet cinema, having started his career in the silent film era of the 1920s.

- The film was produced in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), which was a major center of Soviet film production alongside Moscow.

- The communal house setting was typical of Soviet urban living arrangements in the early 1930s, where multiple families often shared apartments.

- Pyotr Kirillov, who played Sergei, was a prominent actor in Soviet comedy films during the 1930s and early 1940s.

- The film's title 'Crown Prince of the Republic' was ironic, as the Soviet Union had officially abolished monarchy and noble titles.

- Like many Soviet films of this era, the original negative was likely stored in the Gosfilmofond archive, the state film repository.

- The film was released during a period when Soviet comedy was transitioning from the experimental styles of the 1920s to more conventional narrative forms.

- The architect characters reflected the Soviet emphasis on modernization and the building of a new socialist society.

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet reviews of the film likely emphasized its positive social messages and accessible entertainment value, in line with the critical standards of the Socialist Realist era. Critics would have praised its depiction of collective living and professional dedication while ensuring the comedy did not undermine socialist values. Modern assessments of the film are limited due to its relative obscurity and availability, but film historians recognize it as a representative example of mainstream Soviet comedy production during the mid-1930s. The film is generally viewed as a competent but not particularly distinguished work that successfully met the ideological and entertainment requirements of its time.

What Audiences Thought

The film likely found moderate success with Soviet audiences seeking light entertainment during a period of intense social and economic transformation. The comedic elements and relatable domestic situations would have appealed to viewers looking for diversion from the pressures of industrialization and collectivization. The presence of popular actors like Pyotr Kirillov would have drawn audiences familiar with his work in other Soviet comedies. However, like many Soviet films of the 1930s, its reception was ultimately secondary to its fulfillment of ideological and cultural policy requirements.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Soviet comedies of the 1920s

- Socialist Realist doctrine

- Traditional Russian theatrical comedy

- Contemporary American screwball comedies

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Soviet domestic comedies of the late 1930s

- Post-war Soviet family comedies