Dahej

"A powerful social drama exposing the evil of dowry"

Plot

Thakur, a proud and dignified man, adores his only daughter Chanda and wants the best for her future. When a marriage proposal arrives from the respectable household of a lawyer and his wife, Thakur gladly accepts but makes it explicitly clear that he cannot afford to provide any dowry. Despite this understanding, the wedding proceeds, and Chanda enters her new home with hopes of happiness. However, the situation quickly deteriorates as Chanda's mother-in-law begins systematically harassing and tormenting her about the lack of dowry, subjecting her to emotional and psychological abuse. The film chronicles Chanda's suffering under this dowry-related persecution and her father's anguish as he witnesses his daughter's misery. The narrative serves as a powerful social commentary on the destructive practice of dowry in Indian society and its devastating impact on women and their families.

About the Production

Directed by the legendary V. Shantaram as part of his series of socially relevant films that addressed pressing issues in Indian society. The film was produced during the early years of independent India when filmmakers were increasingly using cinema as a medium for social reform. V. Shantaram was known for his commitment to social themes and used this film to highlight the dowry system's detrimental effects. The production faced some resistance from conservative elements who felt the topic was too controversial for cinema.

Historical Background

Dahej was produced in 1952, just five years after India gained independence from British rule. This period was marked by intense nation-building efforts and social reform movements across the country. The Indian government, under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, was actively promoting social reforms to eliminate practices like dowry, child marriage, and caste discrimination. The film emerged during the golden age of Indian cinema, when filmmakers were increasingly using their medium to address social issues and contribute to nation-building. The early 1950s also saw the establishment of the Filmfare Awards in 1954, which would become India's most prestigious film honors. The dowry system, despite being legally discouraged, remained deeply entrenched in Indian society, making films like Dahej crucial in raising public awareness. The film's release coincided with growing women's rights movements in India and increasing discussions about women's education and empowerment in the newly independent nation.

Why This Film Matters

Dahej holds significant cultural importance as one of the earliest mainstream Indian films to directly confront the dowry system, a practice that continues to plague Indian society decades later. The film contributed to the growing discourse around women's rights and gender equality in post-independence India. It helped establish cinema as a powerful medium for social reform and awareness, influencing generations of filmmakers to address social issues through their work. The film's portrayal of the suffering caused by dowry demands resonated deeply with audiences, many of whom had experienced similar situations in their own families. Dahej also contributed to the stereotype of the cruel mother-in-law in Indian popular culture, a trope that would be repeated in countless films and television shows. The film's legacy extends to contemporary Indian cinema, where social messaging remains an important element of mainstream filmmaking. Its impact can be seen in the numerous dowry-related films that followed, each building upon the foundation laid by early social dramas like Dahej.

Making Of

The making of 'Dahej' reflected V. Shantaram's commitment to socially relevant cinema. As director and producer, he took significant creative risks by tackling the sensitive subject of dowry at a time when such topics were rarely addressed in mainstream cinema. The casting of Prithviraj Kapoor as Thakur was a strategic choice, as his stature in Indian theatre and cinema lent credibility to the film's serious message. Lalita Pawar's transformation into the cruel mother-in-law was so convincing that it reportedly affected her public image, with people often treating her with fear in real life. The film's production involved extensive research into real-life dowry cases to ensure authenticity in depicting the harassment faced by brides. V. Shantaram worked closely with his writers to craft a narrative that would be both emotionally engaging and socially impactful, using the melodramatic elements popular in Indian cinema to deliver a serious social message. The filming process was reportedly challenging due to the emotional intensity of certain scenes, particularly those depicting the harassment of the bride.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Dahej reflected the stylistic conventions of early 1950s Indian cinema while effectively serving the film's dramatic narrative. The visual style emphasized high-contrast lighting to enhance the emotional intensity of key scenes, particularly those depicting the bride's suffering. Camera work was relatively static by modern standards but used careful composition to highlight the power dynamics between characters. The cinematographer employed medium close-ups to capture the emotional states of the characters, especially during confrontations between Chanda and her mother-in-law. The visual palette was dominated by earthy tones and shadows, creating a somber atmosphere appropriate to the film's serious subject matter. The film used lighting to symbolically represent the protagonist's journey from hope to despair, with brighter scenes in the early portions giving way to darker visuals as the harassment intensified. The visual storytelling complemented the narrative's emotional arc, using framing and composition to reinforce the themes of oppression and resilience.

Innovations

While Dahej did not introduce groundbreaking technical innovations, it demonstrated sophisticated use of existing film techniques to enhance its social message. The film employed effective sound design to emphasize the emotional impact of confrontational scenes, using silence strategically to heighten tension. The editing techniques, while conventional for the period, effectively paced the narrative to build emotional intensity gradually. The production design created authentic domestic environments that helped audiences relate to the characters' situations. The film's technical approach prioritized clarity and emotional impact over stylistic experimentation, reflecting V. Shantaram's focus on message delivery. The makeup and costume design were particularly effective in character development, especially in transforming Lalita Pawar into the intimidating mother-in-law. The film's technical achievements lay in its successful integration of various cinematic elements to create a cohesive and powerful social narrative. The technical team's work demonstrated how conventional film techniques could be used effectively to address serious social issues.

Music

The music for Dahej was composed by Vasant Desai, a frequent collaborator with V. Shantaram who was known for his ability to create music that enhanced the emotional impact of social dramas. The soundtrack featured a mix of classical and folk-inspired melodies that reflected the film's rural setting and traditional values. The songs were not merely entertainment but served to advance the narrative and highlight key emotional moments. Notable tracks included poignant numbers that expressed the protagonist's suffering and her father's anguish. The lyrics, written by respected poets of the era, carried social messages that reinforced the film's themes. The background score used traditional Indian instruments to create an authentic atmosphere while employing Western orchestral techniques to heighten dramatic tension. The soundtrack was well-received for its ability to complement the film's serious tone without overwhelming the narrative. Music played a crucial role in making the film's social message accessible to mainstream audiences of the time.

Famous Quotes

"Dahej nahi denge, par beti ki izzat zaroor denge" (We won't give dowry, but we will definitely give our daughter's honor)

"Beti ki khushi hi hamara daulat hai" (Our daughter's happiness is our wealth)

"Yeh dahej ka riwaz hamare samaj ko kha raha hai" (This custom of dowry is eating away our society)

Memorable Scenes

- The emotional confrontation between Thakur and the lawyer where he proudly declares his inability to pay dowry but offers his daughter's virtues instead

- The series of scenes showing Chanda's systematic harassment by her mother-in-law, each escalating in cruelty

- The heartbreaking moment when Chanda writes a letter to her father describing her suffering

- The climactic scene where Thakur confronts his daughter's in-laws about their treatment of Chanda

- The final resolution scene that delivers the film's powerful social message about ending the dowry system

Did You Know?

- Director V. Shantaram was a pioneer of social cinema in India and used 'Dahej' as part of his mission to create awareness about social evils

- The film was one of the earliest mainstream Indian films to directly address the dowry system, a topic considered taboo in cinema of that era

- Lalita Pawar, who played the antagonistic mother-in-law, was famous for her negative roles and became one of Bollywood's most memorable villains

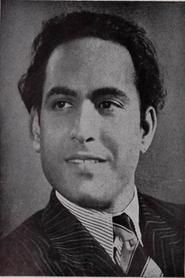

- Prithviraj Kapoor, a legendary figure in Indian theatre and cinema, brought gravitas to the role of the principled father

- The film's title 'Dahej' literally translates to 'dowry' in Hindi, making its social message immediately clear to audiences

- V. Shantaram's production company Rajkamal Kalamandir was known for producing films with strong social messages

- The film was released just five years after India's independence, during a period of intense social reform and nation-building

- Despite its serious subject matter, the film incorporated elements of family drama to make it accessible to mainstream audiences

- The screenplay was written to balance social commentary with emotional storytelling to maximize its impact

- The film was part of a broader movement in Indian cinema that used melodrama to address social issues

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Dahej for its courage in addressing a sensitive social issue and its powerful emotional storytelling. The film was particularly lauded for V. Shantaram's direction and the performances of its lead actors. Critics noted how effectively the film used melodrama to convey its social message without being preachy. The Times of India highlighted the film's importance in bringing the dowry issue to mainstream attention. Modern film historians recognize Dahej as a pioneering work in Indian social cinema, often citing it as an example of how cinema can be used for social change. The film is now studied in film schools as an early example of socially relevant Indian cinema that successfully blended entertainment with social messaging. Critics have noted that while the film's style may appear dated to contemporary audiences, its message remains relevant and powerful.

What Audiences Thought

Dahej resonated strongly with audiences in 1952, many of whom had personal experience with the dowry system's devastating effects. The film's emotional portrayal of a young bride's suffering struck a chord with viewers, particularly women who had faced similar pressures. Audience reports from the time indicate that many viewers were moved to tears by the film's powerful scenes of harassment and emotional abuse. The film sparked discussions in families and communities about the practice of dowry, with some reports of viewers reconsidering their own attitudes toward the practice. While the film was not a blockbuster in commercial terms, it achieved moderate box office success and was remembered more for its social impact than its financial performance. The film's reputation has grown over time, with film enthusiasts and scholars recognizing its importance in Indian cinema history. Modern audiences who have seen the film through retrospectives and film festivals continue to appreciate its bold social commentary and emotional power.

Awards & Recognition

- Filmfare Award for Best Film (Nomination, 1953)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Indian social reform movements of the 1950s

- Traditional Indian folk tales about marital oppression

- Early Indian theatrical traditions addressing social issues

- V. Shantaram's previous social films including 'Shakuntala' and 'Dr. Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani'

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Indian films addressing dowry including 'Nadiya Ke Paar' (1982), 'Saajan Bina Suhagan' (1978), and modern films like 'Dil Dhadakne Do' (2015) which touched upon dowry-related issues

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of Dahej is concerning, as many Indian films from the 1950s have been lost due to poor archival practices. While some prints may exist in private collections or film archives, there is no confirmed restoration project for this film. The Film Heritage Foundation and other Indian film preservation organizations have been working to identify and restore classic Indian films, but Dahej's status remains uncertain. Some portions of the film may be available in degraded condition through collectors or in film institute archives. The lack of a proper digital restoration means that contemporary audiences have limited access to this important social drama. The film's preservation challenges reflect the broader crisis of Indian film heritage, with an estimated 70% of Indian films made before 1950 believed to be lost forever.