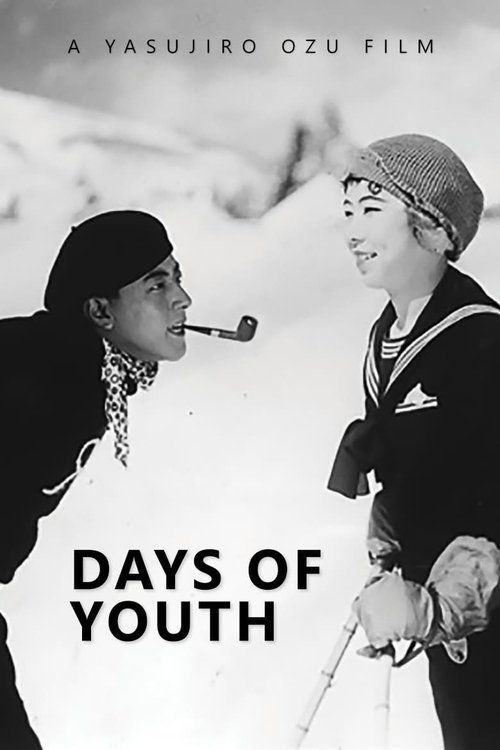

Days of Youth

Plot

Days of Youth follows two college friends, Watanabe and Yamamoto, who both develop feelings for the same young woman named Chieko during a winter skiing trip. Unaware that they are rivals for her affection, the two friends engage in various competitions and humorous situations while trying to impress her. The film explores themes of friendship, youthful romance, and the awkward dynamics of young love against the backdrop of Japan's winter landscapes. As their rivalry intensifies, both friends must navigate their feelings for Chieko while maintaining their friendship. The story culminates in a resolution that tests the bonds of their friendship and their understanding of love and maturity.

About the Production

This was one of Ozu's earliest surviving works, made during his apprenticeship period at Shochiku. The film was shot during winter months to capture authentic skiing sequences, which was challenging for the cast and crew given the limited technology of the time. The skiing scenes were particularly innovative for Japanese cinema, requiring special equipment and techniques to film on snow. Ozu was still developing his distinctive style, and the film shows influences from American comedies while beginning to show his unique perspective on Japanese society.

Historical Background

Days of Youth was released in 1929, a pivotal year in world cinema history as the transition from silent to sound films was underway globally. In Japan, this transition would happen more slowly than in Hollywood, allowing silent films to continue being produced into the early 1930s. The film emerged during Japan's Taishō democracy period, a time of increasing Western influence and modernization in Japanese society. The story of college students and their romantic pursuits reflected the growing youth culture and changing social norms in urban Japan. The film's focus on skiing as a leisure activity also highlighted the adoption of Western sports among Japan's middle and upper classes. This was also the year of the Great Depression's beginning, though Japan's economy would not be as immediately affected as Western nations.

Why This Film Matters

Days of Youth holds significant cultural importance as one of the earliest surviving examples of Yasujirō Ozu's work, providing insight into his artistic development before he became one of cinema's most revered directors. The film represents an important document of Japanese youth culture in the late 1920s, capturing the tensions between traditional Japanese values and Western modernization. Its preservation and restoration have allowed film scholars to trace the evolution of Ozu's distinctive cinematic language. The film also contributes to our understanding of how Japanese cinema was developing its own identity while being influenced by Hollywood productions. As a student comedy, it shows how Japanese filmmakers were adapting genre conventions to reflect Japanese social realities and values.

Making Of

Days of Youth was produced during Ozu's formative years at Shochiku Studios, where he had worked his way up from assistant director. The film was part of a series of student comedies and youth dramas that Ozu directed in the late 1920s. The skiing scenes presented particular challenges, as the cast had to learn to ski for the film, and the camera equipment of the era was difficult to operate in cold, snowy conditions. Ozu collaborated with cinematographer Hideo Shigehara, who would become one of his key collaborators. The film's production reflected the studio's strategy of creating films that would appeal to younger audiences and Japan's growing middle class. During filming, Ozu was already developing his meticulous approach to composition, though his later distinctive low camera angles were not yet fully established.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Days of Youth was handled by Hideo Shigehara, who would become one of Ozu's most important collaborators. While not yet displaying the fully matured Ozu style, the film shows early experimentation with composition and camera placement. The skiing sequences required innovative techniques to capture movement on snow, using tracking shots and dynamic angles that were relatively advanced for Japanese cinema of the period. The film employs a mix of studio sets and location filming, with the outdoor scenes providing a visual contrast to the interior sequences. The cinematography reflects the influence of American silent comedies in its approach to visual storytelling, though it also begins to show the more contemplative, observational style that would become Ozu's trademark.

Innovations

Days of Youth achieved several technical milestones for its time in Japanese cinema. The filming of skiing sequences represented a significant technical challenge, requiring specialized equipment and techniques to operate cameras in cold, snowy conditions. The successful integration of location filming with studio work demonstrated the growing sophistication of Japanese film production. The film's preservation and restoration have also been technically noteworthy, allowing modern audiences to experience this rare early work. While not as technically innovative as some contemporary films, it demonstrated solid craftsmanship and the growing technical capabilities of the Japanese film industry during the late 1920s.

Music

As a silent film, Days of Youth did not have an original recorded soundtrack. During its original theatrical run, the film would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically a piano or small ensemble, and most importantly, a benshi narrator who would provide voice-over narration, character voices, and commentary. The benshi tradition was a crucial element of Japanese silent cinema, with some narrators becoming as famous as the actors themselves. The musical accompaniment would have consisted of popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and improvisational music that matched the on-screen action and emotional tone. Modern screenings of the restored film typically feature newly composed scores or carefully selected period-appropriate music.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and visual storytelling rather than spoken quotes

Memorable Scenes

- The skiing competition sequence where Watanabe and Yamamoto race to impress Chieko, showcasing impressive early winter sports cinematography

- The scene where both friends unknowingly plan to meet Chieko at the same location, leading to comic confusion

- The final resolution where the friends discover their rivalry and must choose between their friendship and their romantic pursuits

Did You Know?

- This is the earliest surviving complete film directed by Yasujirō Ozu, though it was not his first film as a director

- The film was originally titled 'Wakaki Hi' in Japanese, which translates to 'Young Days' or 'Days of Youth'

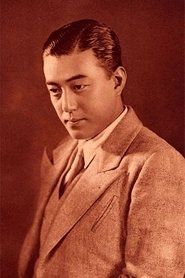

- Ozu was only 26 years old when he directed this film, early in his career at Shochiku Studios

- The skiing sequences were among the first winter sports scenes ever filmed in Japanese cinema

- The film was considered lost for many years before a print was discovered and preserved

- Ozu's famous 'pillow shots' - still images between scenes - are beginning to develop in this early work

- The film showcases Ozu's early interest in the lives of young people and their romantic entanglements

- Like many Japanese silent films, it would have been accompanied by a live benshi narrator during original screenings

- The film's comedic elements show the influence of American silent comedies that Ozu admired

- This was one of the last films Ozu made before his distinctive style fully matured in the 1930s

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Days of Youth is difficult to document due to the limited preservation of Japanese film criticism from this era. However, the film was generally well-received as an entertaining youth comedy that successfully appealed to its target audience of young urban Japanese. Modern critics and film scholars have reevaluated the film as an important early work in Ozu's filmography, noting how it contains seeds of his later masterpieces. Critics have pointed out the film's technical competence, its effective use of location filming for the skiing sequences, and how it already shows Ozu's interest in the details of everyday life. While not considered among Ozu's greatest works, it is valued as a crucial piece in understanding his artistic development and the evolution of Japanese cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Original audience reception for Days of Youth was reportedly positive, particularly among younger viewers who could relate to the college setting and romantic themes. The film's skiing sequences were especially popular, as winter sports were relatively new and exciting to Japanese audiences of the time. The comedy elements and the relatable story of friendship and rivalry resonated with urban audiences. Like many silent films, the experience would have been enhanced by live benshi narration, which added cultural context and emotional depth to the viewing experience. Modern audiences who have seen the film through retrospectives and restorations generally appreciate it as a fascinating early work by a master director, though its entertainment value for contemporary viewers may be limited by its age and silent format.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- American silent comedies

- Harold Lloyd films

- Buster Keaton

- Charlie Chaplin

- German expressionist cinema

- Contemporary Japanese student films

This Film Influenced

- I Graduated, But... (1929)

- I Flunked, But... (1930)

- The Lady and the Beard (1931)

- I Was Born, But... (1932)

- A Mother Should be Loved (1934)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Days of Youth is considered a preserved film, though it was believed lost for many years before a print was discovered. The film has been restored and is part of the collection of major film archives, including the National Film Center of Japan. The restoration has allowed the film to be included in retrospectives of Ozu's work and early Japanese cinema. While not complete in all versions, enough of the film survives to provide a comprehensive view of Ozu's early directorial style.