Faces of Children

"A masterpiece of psychological insight into the heart of childhood"

Plot

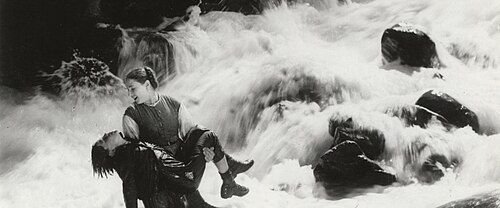

Set in the breathtaking Swiss Alps, 'Faces of Children' follows young Jean, a sensitive boy devastated by his mother's death. When his father remarries, Jean must adjust to a new stepmother and stepsister, experiencing intense jealousy and resentment toward his new family members. The film masterfully portrays Jean's emotional turmoil as he struggles with grief, feelings of betrayal, and the complex dynamics of a blended family. Through a series of poignant events, including a dangerous mountain excursion and moments of raw emotional confrontation, Jean gradually begins to heal and accept his new reality. The narrative culminates in a powerful resolution where Jean learns to open his heart to his new family while still honoring his mother's memory.

About the Production

The film was shot on location in the Swiss Alps during winter, presenting extreme challenges for the cast and crew. Temperatures often dropped below freezing, and the crew had to transport heavy camera equipment up mountain paths. Director Jacques Feyder insisted on natural lighting and authentic locations, which meant filming was dependent on weather conditions. The child actors, particularly Jean Forest, delivered remarkably naturalistic performances, a rarity for the era. Feyder spent months preparing the children for their roles, using innovative psychological techniques to elicit genuine emotions.

Historical Background

Produced during the golden age of French silent cinema, 'Faces of Children' emerged in a period when European filmmakers were pushing the boundaries of cinematic expression. The mid-1920s saw the rise of psychological realism in cinema, moving away from theatrical traditions. The film was created during the stabilization of the French economy after World War I, allowing for more ambitious artistic projects. It coincided with the growing influence of psychoanalysis in European intellectual circles, which informed the film's approach to child psychology. The Swiss setting reflected the era's fascination with nature as a metaphor for emotional states, and the film's emphasis on location shooting anticipated the documentary-inspired realism that would influence neorealist cinema in the following decades.

Why This Film Matters

'Faces of Children' revolutionized the portrayal of childhood in cinema, moving away from sentimentalized or melodramatic depictions to present children as complex psychological beings. The film's naturalistic approach to child acting influenced generations of filmmakers and established new standards for working with young performers. It contributed to the development of psychological realism in cinema, predating and influencing the more famous works of directors like Jean Renoir and later Ingmar Bergman. The film's success demonstrated that serious, psychologically complex stories could find audiences, paving the way for more sophisticated narratives in popular cinema. Its restoration and revival in the 1970s sparked renewed interest in French silent cinema and led to a reevaluation of Feyder's contribution to film history.

Making Of

Jacques Feyder approached this film with unprecedented psychological depth for the era. He spent extensive time observing children's behavior and consulted with child psychologists to understand the grieving process in young people. The casting process was rigorous - Feyder auditioned over 200 children before selecting Jean Forest for the lead role. The production faced numerous challenges, including avalanches, equipment failures in the cold, and the difficulty of working with child actors in harsh conditions. Feyder developed a unique method of directing children, using games and storytelling rather than traditional instruction to elicit authentic performances. The stepmother character was carefully written to avoid villainization, instead presenting a complex, sympathetic figure struggling to connect with her stepson. The film's famous mountain climax sequence required the crew to camp at high altitude for weeks to capture the perfect weather conditions.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Léonce-Henri Burel was revolutionary for its time, combining breathtaking Alpine landscapes with intimate psychological moments. Burel employed natural lighting extensively, particularly in the mountain sequences, creating a visual poetry that mirrored the emotional states of the characters. The film features innovative use of deep focus and dynamic camera movement, techniques that were rare in 1925. The contrast between the vast, indifferent mountains and the close-up shots of the children's faces creates a powerful visual metaphor for the individual's struggle against overwhelming forces. Burel's work influenced the development of location cinematography and established new possibilities for using natural environments to enhance psychological storytelling.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would influence cinema for decades. Its extensive use of location shooting in difficult mountain terrain required the development of portable camera equipment and new techniques for filming in extreme weather conditions. The film's sophisticated use of focus and depth of field was ahead of its time, creating visual complexity that enhanced the psychological narrative. The production team developed new methods for recording sound on location (for synchronization purposes in theaters with live accompaniment) and innovative lighting techniques for shooting in snow-covered landscapes. The film's editing style, particularly in its handling of the children's performances, established new standards for psychological pacing in cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'Faces of Children' was originally accompanied by live musical scores that varied by theater and region. The original French premiere featured a specially composed score by Arthur Honegger, though this music has been lost. The film's emotional structure suggests it was designed to accommodate both classical and folk musical elements, particularly Swiss Alpine themes. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores, most notably a 1995 composition by Timothy Brock that attempts to recreate the emotional tone of the original accompaniment. The film's rhythm and pacing demonstrate Feyder's sophisticated understanding of how visual narrative and musical accompaniment work together to create emotional impact.

Famous Quotes

"A child's face is the most honest mirror of the soul" - Jacques Feyder's director's note

"In the mountains, as in the heart, paths can be both beautiful and dangerous" - Opening intertitle

"Sometimes the hardest mountains to climb are the ones in our own hearts" - Mid-film intertitle

"Love, like snow, can cover old wounds with something pure and new" - Closing intertitle

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Jean's isolated play in the snow, establishing his loneliness

- The tense dinner scene where Jean first meets his stepmother and stepsister

- The dangerous mountain climb where Jean attempts to run away, culminating in his rescue

- The emotional breakdown scene where Jean finally cries for his mother

- The final reconciliation scene where Jean accepts his new family while honoring his mother's memory

Did You Know?

- The film's French title 'Visages d'enfants' is considered more accurate in capturing the psychological depth of the story

- Jean Forest, who played Jean, was discovered by Feyder in a schoolyard and became one of the most celebrated child actors of the 1920s

- The film was initially a commercial disappointment but was later recognized as a masterpiece of French cinema

- Director Jacques Feyder was married to actress Françoise Rosay, who appeared in several of his films

- The mountain scenes were filmed without stunt doubles, with actors performing their own climbing sequences

- The film was banned in several countries for its psychological intensity and depiction of childhood trauma

- It was one of the first films to extensively use location shooting for psychological effect

- The original negative was thought lost for decades before being rediscovered in the 1970s

- Feyder spent six months in the Alps before filming to study the local culture and environment

- The film influenced later psychological dramas and was particularly admired by directors like Jean Renoir

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics hailed the film as a breakthrough in psychological cinema, with particular praise for its naturalistic performances and Feyder's sensitive direction. French critics compared its emotional depth to the works of Dostoevsky, while international reviewers noted its revolutionary approach to child psychology. The film was especially admired in Germany and Russia, where it influenced the development of psychological cinema. Modern critics consider it a masterpiece of silent cinema, often citing it as Feyder's greatest work. The film's reputation has grown over time, with contemporary scholars recognizing its influence on subsequent psychological dramas and its pioneering role in establishing new standards for child performance in cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience response was mixed, with some finding the film's psychological intensity challenging for mainstream entertainment. However, it developed a cult following among intellectuals and cinema enthusiasts who appreciated its artistic ambitions. The film found particular success in art house circuits and was especially popular in Scandinavian countries, where its naturalistic style resonated with local cinematic traditions. Over time, audience appreciation has grown significantly, with modern viewers often struck by its contemporary relevance and emotional authenticity. The film's restoration and availability on home video have introduced it to new generations, who frequently praise its timeless exploration of family dynamics and childhood emotions.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Artistic Production at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts

- Best Director (Jacques Feyder) at the 1925 French Film Critics Awards

- Best Cinematography at the 1925 Brussels Film Festival

Film Connections

Influenced By

- D.W. Griffith's psychological dramas

- German Expressionist cinema's emotional intensity

- Victor Sjöström's nature symbolism

- F.W. Murnau's visual storytelling

- French literary realism

- Psychoanalytic theory of the 1920s

This Film Influenced

- The 400 Blows

- The Spirit of the Beehive

- Fanny and Alexander

- The White Ribbon

- The Kid

- Ponette

- Children of Paradise

- The River

- Small Change

- The Miracle of the Little Prince

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for decades until a complete print was discovered in the Czechoslovakian film archives in the 1970s. The film underwent major restoration by the Cinémathèque Française in 1993, with additional restoration work completed in 2008. The restored version is now considered complete and is preserved in several major film archives worldwide, including the Cinémathèque Française, the Museum of Modern Art, and the British Film Institute. The restoration process involved piecing together elements from multiple sources and digitally repairing damage to the original nitrate print.