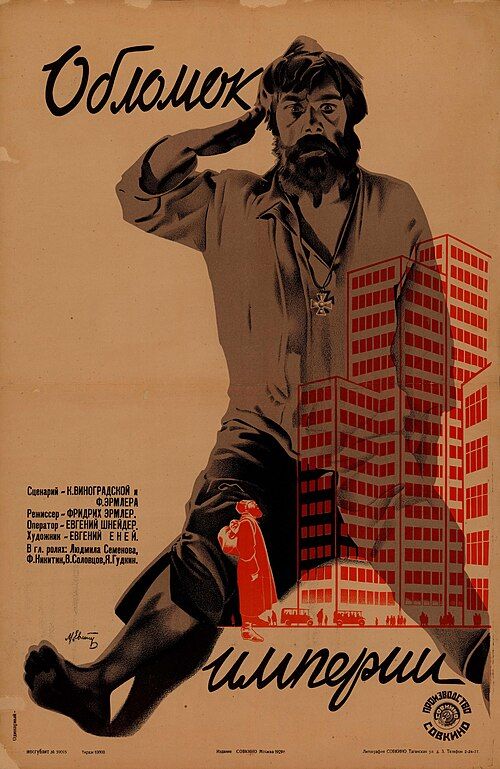

Fragment of an Empire

Plot

Set in the aftermath of World War I and the Russian Revolution, Fragment of an Empire follows the story of Imperial Russian officer Filimonov, who suffers from shell-shock and amnesia after being wounded in battle. For ten years, he wanders Russia with no memory of his past, until a chance glimpse of a woman through a train window triggers the return of his memories. Filimonov makes his way back to what was once St. Petersburg, now renamed Leningrad, where he discovers that the world he knew has completely vanished. The aristocratic society he belonged to has been replaced by Soviet collectivism, and he finds himself a living relic of a bygone era. Struggling to adapt to the new social order and reunite with his lost love, Filimonov must confront the painful reality that his former life is truly gone, forcing him to choose between clinging to the past or embracing the revolutionary present.

About the Production

The film was shot on location in Leningrad, utilizing the city's actual architecture to contrast Imperial and Soviet periods. Ermler employed innovative techniques including flashbacks and subjective camera work to depict the protagonist's psychological state. The production faced challenges in recreating pre-revolutionary St. Petersburg while filming in the Soviet-transformed city. The film's title was initially 'The Man Who Lost His Memory' before being changed to 'Fragment of an Empire' to better reflect its broader themes about the collapse of Imperial Russia.

Historical Background

Fragment of an Empire was produced during a crucial transitional period in Soviet cinema and society. The late 1920s saw the Soviet film industry at its artistic peak, with directors like Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov creating groundbreaking works. However, this was also the beginning of increased state control over artistic expression, with Stalin's consolidation of power leading to stricter ideological requirements for films. The film's release in 1929 coincided with the first Five-Year Plan and the forced collectivization of agriculture, making its themes of social transformation particularly relevant. The movie's sympathetic portrayal of a pre-revolutionary officer was daring for its time, as most Soviet films of the period presented the old regime in purely negative terms. The film emerged just as the Soviet industry was transitioning to sound technology, making it part of the final generation of great Soviet silent films.

Why This Film Matters

Fragment of an Empire represents a unique perspective on the Russian Revolution and its aftermath, offering a more nuanced view than typical Soviet propaganda films of the era. The film's exploration of memory, identity, and the psychological impact of social upheaval anticipated later European art cinema movements. Its technical innovations, particularly in depicting subjective psychological states, influenced subsequent Soviet filmmakers. The movie's humanistic approach to its protagonist, despite his aristocratic background, demonstrated a complexity rare in Soviet cinema of the period. The film's restoration and rediscovery in the 1960s sparked renewed interest in Ermler's work and contributed to scholarly reassessment of Soviet silent cinema. Today, it is studied as an important example of how filmmakers navigated artistic expression within ideological constraints, and as a valuable historical document of how the revolution was processed and understood by those who lived through it.

Making Of

Fridrikh Ermler and Fyodor Nikitin had already established a successful creative partnership through three previous films, and Fragment of an Empire represented the culmination of their collaboration. Ermler spent months researching the psychological effects of shell shock and amnesia to ensure authenticity in Nikitin's portrayal. The production faced significant challenges in obtaining permission to film certain locations in Leningrad, as authorities were concerned about the film's portrayal of the pre-revolutionary era. The train sequence, crucial to the plot, required complex coordination between the camera crew, actors, and railway authorities. Ermler experimented with innovative editing techniques, including rapid cross-cutting between past and present to convey the protagonist's disorientation. The film's restoration in the 1960s revealed that several scenes had been cut after the initial release, likely due to political concerns about their content.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Yevgeni Schneider employed innovative techniques to convey the protagonist's psychological state, including soft focus, unusual camera angles, and subjective point-of-view shots. The film made striking use of contrast between the opulent architecture of Imperial St. Petersburg and the functionalist aesthetic of Soviet Leningrad. Schneider's camera work during the train sequence was particularly noteworthy, using tracking shots and rapid editing to simulate the disorienting experience of memory returning. The battle scenes utilized handheld camera techniques unusual for the period to create a sense of chaos and confusion. The film's visual style evolved as the protagonist's memory returned, with the cinematography becoming more stable and conventional as he reoriented himself to reality.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in Soviet cinema, particularly in depicting psychological states through visual means. Ermler and his team developed new techniques for showing memory flashbacks, using double exposure and rapid editing to convey the fragmented nature of recollection. The train sequence required the construction of a specialized camera mounting system that could move smoothly while capturing the protagonist's perspective through the window. The film's makeup effects, particularly those showing the passage of time on the protagonist's face, were considered advanced for the period. The production team also developed new methods for creating the visual contrast between past and present, using different film stocks and processing techniques for different time periods.

Music

As a silent film, Fragment of an Empire would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score would have been compiled from existing classical pieces and popular songs of the era, tailored by local musicians to match the film's emotional arc. During the 1960s restoration, composer Vladimir Dashkevich created a new orchestral score specifically designed to complement the film's themes of memory and loss. Modern screenings often feature either Dashkevich's score or newly commissioned works by contemporary composers who specialize in silent film accompaniment. The original musical cues and suggestions for accompaniment, if they existed, have not survived in the archival record.

Famous Quotes

I remember everything now... but nothing is the same.

This city is familiar, but it speaks a different language.

How can a man be a stranger in his own home?

The empire I served was just a fragment after all.

Memory is both a gift and a curse in times like these.

Memorable Scenes

- The pivotal train sequence where Filimonov sees a woman through the window and his memories come flooding back, using rapid cuts and soft focus to convey the overwhelming return of consciousness

- Filimonov's first walk through Soviet Leningrad, where the camera follows his disoriented gaze as he struggles to recognize familiar landmarks transformed by revolutionary change

- The emotional reunion scene where Filimonov confronts his lost love, now married to a Soviet worker, highlighting the personal costs of political transformation

- The opening battle sequence that establishes Filimonov's shell shock through innovative camera work and editing techniques

Did You Know?

- This was Fridrikh Ermler's final silent film before transitioning to sound cinema

- The film was banned in the Soviet Union shortly after its release for being too sympathetic to the old regime

- Fyodor Nikitin's performance was particularly praised for its psychological depth and subtlety

- The film was considered lost for decades before being rediscovered and restored in the 1960s

- Ermler used actual war veterans as extras to add authenticity to the battle scenes

- The train sequence where Filimonov regains his memory was shot using a specially constructed camera rig

- The film's themes of memory and identity were highly unusual for Soviet cinema of the late 1920s

- Contemporary critics noted the film's unusual blend of Soviet propaganda with humanist storytelling

- The production team had to recreate pre-revolutionary costumes and props from memory and photographs

- The film was one of the last major Soviet silent productions before the industry fully converted to sound

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film's technical achievements and Nikitin's performance, though some expressed concern about its sympathetic treatment of a pre-revolutionary officer. The film was noted for its sophisticated editing and psychological depth, with particular acclaim for its innovative use of flashback sequences. Western critics who saw the film during its limited international release recognized it as a significant work of Soviet cinema, comparing it favorably to the better-known works of Eisenstein and Pudovkin. After the film's rediscovery and restoration in the 1960s, critics reevaluated it as a masterpiece of late Soviet silent cinema, praising its complex themes and humanistic approach. Modern film scholars consider it one of Ermler's most accomplished works and an important bridge between the experimental Soviet cinema of the 1920s and the more conventional socialist realism of the 1930s.

What Audiences Thought

Initial Soviet audience reception was mixed, with some viewers moved by the protagonist's plight while others questioned the film's ideological purity. The film's limited release due to political concerns meant that relatively few Soviet citizens saw it during its original run. International audiences who had the opportunity to view the film at special screenings generally responded positively to its emotional power and technical sophistication. After its restoration, the film found new audiences among film enthusiasts and scholars, who appreciated its unique perspective on revolutionary history. Modern viewers often comment on the film's surprising emotional depth and its relevance to contemporary discussions about social change and personal identity.

Awards & Recognition

- Named one of the greatest Soviet films of all time by Soviet film critics in the 1920s

- Retrospective recognition at the 1975 Moscow International Film Festival

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema (particularly in psychological depiction)

- Soviet montage theory

- Friedrich Murnau's 'The Last Laugh' (for subjective camera work)

- Vsevolod Pudovkin's psychological films

This Film Influenced

- Andrei Tarkovsky's 'Mirror' (themes of memory and time)

- Sergei Parajanov's 'Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors' (visual poetry)

- Alexander Sokurov's 'Russian Ark' (historical reflection)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for several decades before being rediscovered in the Soviet film archives in the 1960s. A restoration project was undertaken by Gosfilmofond, the Russian state film archive, which reconstructed the film from existing prints and negative fragments. The restored version premiered at the 1975 Moscow International Film Festival. The film is now preserved in the Gosfilmofond collection and has been made available in various digital formats for archival and educational purposes. Some scenes that were cut after the original release remain lost, but the restored version is considered largely complete.