From the Manger to the Cross

"The Greatest Story Ever Told Filmed in the Land Where It Happened"

Plot

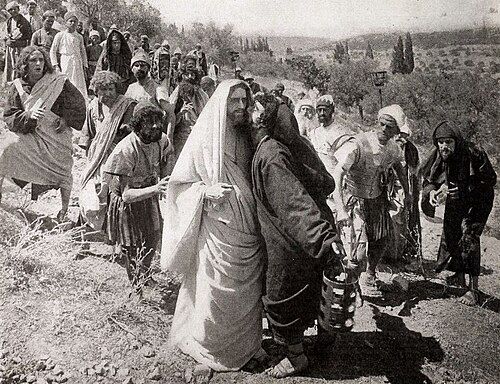

From the Manger to the Cross chronicles the life of Jesus Christ through a series of carefully staged tableaux, beginning with the Nativity in Bethlehem and the visit of the Magi. The film follows Jesus's ministry, including his baptism by John the Baptist, the Sermon on the Mount, and his miracles of healing the sick and feeding the multitude. The narrative builds toward the dramatic events of Holy Week, depicting Jesus's triumphant entry into Jerusalem, the Last Supper with his disciples, and his betrayal in the Garden of Gethsemane. The film culminates in the powerful sequences of Jesus's trial before Pontius Pilate, his crucifixion on Calvary, and ultimately his resurrection and ascension into heaven. Throughout the production, the filmmakers utilized authentic Holy Land locations to lend unprecedented visual authenticity to the biblical story.

About the Production

This was the first feature-length film shot on location in the Holy Land, requiring the cast and crew to travel for months by ship, train, and camel. The production faced numerous challenges including dealing with Ottoman authorities, extreme weather conditions, and the logistical difficulties of filming in remote locations with heavy equipment. Director Sidney Olcott and his team had to obtain special permission from Turkish authorities to film in what was then Ottoman territory. The production utilized local people as extras, creating authentic crowd scenes. The filmmakers had to transport and develop film stock in desert conditions, often working with primitive equipment and limited water supplies.

Historical Background

In 1912, the film industry was transitioning from short films to feature-length productions, and From the Manger to the Cross was at the forefront of this evolution. The world was on the brink of World War I, and the Ottoman Empire still controlled Palestine, making Western access to these holy sites difficult and rare. Motion pictures were still seen by many as a novelty or lowbrow entertainment, but this film helped establish cinema as a medium capable of serious artistic and religious expression. The Progressive Era in America saw a growing interest in social reform and moral education, and religious films were seen as a way to uplift audiences. The film's production coincided with increased archaeological interest in the Holy Land and a growing American fascination with biblical tourism. This was also a period when the film industry was establishing itself on the West Coast, though Kalem Company remained based in New York. The success of this film demonstrated that audiences would embrace longer, more ambitious films, paving the way for the feature film industry that would dominate Hollywood in subsequent decades.

Why This Film Matters

From the Manger to the Cross represents a pivotal moment in cinema history, establishing the biblical epic as a legitimate and profitable genre. Its unprecedented use of authentic locations set a new standard for realism in filmmaking that would influence generations of directors. The film's commercial success proved that feature-length films could be viable investments, accelerating the industry's move away from short subjects. Its papal blessing helped legitimize cinema as a medium for religious education and artistic expression, countering criticism from religious leaders who viewed movies as immoral. The film also demonstrated the global potential of American cinema, as it was distributed internationally and particularly successful in Catholic countries. Its preservation in the National Film Registry recognizes its role in shaping American film history. The movie's approach to biblical storytelling influenced countless subsequent films, from Cecil B. DeMille's epics to Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ. It also established visual conventions for depicting Jesus that persisted throughout the 20th century.

Making Of

The production of From the Manger to the Cross was an extraordinary undertaking that pushed the boundaries of early filmmaking. Director Sidney Olcott, known for his innovative location shooting, convinced the Kalem Company to invest in an ambitious Middle Eastern expedition. The crew of approximately 25 people traveled by steamship to Egypt, then through the Suez Canal to Palestine. They faced numerous hardships including disease, extreme temperatures, and cultural barriers. The Ottoman authorities were suspicious of the filmmakers, requiring constant negotiations and payments to secure access to religious sites. Cinematographer George K. Hollister had to work with a hand-cranked camera in challenging lighting conditions, often filming in the harsh desert sun. The cast, led by Robert Henderson-Bland as Jesus, had to perform in heavy period costumes in sweltering heat. Local inhabitants were recruited as extras, many of whom had never seen a motion picture camera before. The production team developed film in makeshift darkrooms, using whatever water was available. Despite these challenges, they managed to capture stunning footage that gave audiences an unprecedented view of the actual locations where biblical events occurred.

Visual Style

George K. Hollister's cinematography was revolutionary for its time, utilizing the vast landscapes and natural lighting of the Holy Land to create images of unprecedented scope and authenticity. The film employed long shots of desert vistas and ancient architecture that gave audiences their first cinematic views of these sacred locations. Hollister mastered the challenges of filming in extreme conditions, using the harsh Middle Eastern sun to create dramatic contrasts and silhouettes. The camera work was notably static compared to modern films, but the compositions were carefully arranged to maximize the impact of the locations. The use of actual ruins and ancient sites as backdrops created a sense of historical authenticity that studio sets could not achieve. The cinematography emphasized the scale of the biblical story, often positioning small human figures against vast landscapes to emphasize the monumental nature of the events. The film also made effective use of natural elements like sandstorms and sunsets to enhance the dramatic impact of key scenes.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was its successful execution of location filming in extremely challenging conditions. The production team adapted heavy, cumbersome film equipment for transport by camel and donkey to remote locations. They developed innovative methods for protecting film stock from extreme heat and sand damage. The cinematographers mastered exposure techniques for the harsh Middle Eastern light, which was significantly different from the lighting conditions in American studios. The film also pioneered techniques for coordinating large crowd scenes with non-professional local actors. The editing structure, using a series of tableaux to tell the story, was innovative for its time and influenced how biblical stories would be presented in film. The production also demonstrated the feasibility of international location shooting, paving the way for future foreign productions. The film's success in maintaining visual continuity despite being shot across multiple locations over several months was a significant technical accomplishment for 1912.

Music

As a silent film, From the Manger to the Cross was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. Most large theaters employed orchestras to perform specially composed scores, while smaller venues used piano accompaniment. The typical score incorporated classical pieces, hymns, and original compositions designed to enhance the emotional impact of each scene. Popular musical selections included works by Bach, Handel, and other composers whose music was considered appropriate for religious subjects. Some theaters reportedly used choirs to provide vocal accompaniment for particularly dramatic moments. The musical direction varied by theater, but the goal was always to create an atmosphere of reverence and solemnity appropriate to the subject matter. Modern restorations of the film have been accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the emotional impact of the original theatrical experience.

Famous Quotes

As intertitle: 'And lo, the star which they saw in the east went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was.'

As intertitle: 'Father, if thou be willing, remove this cup from me: nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done.'

As intertitle: 'It is finished.'

As intertitle: 'Behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people.'

As intertitle: 'Verily I say unto thee, Today shalt thou be with me in paradise.'

Memorable Scenes

- The Nativity scene filmed in the actual countryside near Bethlehem, with real shepherds and their flocks in the background

- The Sermon on the Mount delivered from an actual hillside overlooking the Sea of Galilee

- The dramatic crucifixion sequence filmed against the rocky landscape of Jerusalem, using natural light to create stark shadows

- The baptism scene filmed in the Jordan River, showing Jesus entering the actual waters

- The procession into Jerusalem with palm branches, filmed on the actual road leading to the ancient city

Did You Know?

- This was the first feature-length film to be shot on location in the Holy Land, setting a precedent for biblical epics

- The film was so successful that Pope Pius X granted it a special blessing, making it one of the few films to receive papal approval

- Director Sidney Olcott and his crew spent five months traveling and filming in the Middle East, a remarkable undertaking for 1912

- The film's success helped establish the feature-length format as commercially viable in American cinema

- Robert Henderson-Bland, who played Jesus, was a Shakespearean actor who reportedly studied the Gospels extensively for the role

- The production had to pay bribes to local Ottoman officials to secure filming permits in various locations

- Gene Gauntier, who played Mary, also wrote the screenplay and was one of the most important women in early American cinema

- The film was originally titled 'The Life of Christ' but was changed to 'From the Manger to the Cross' for marketing purposes

- Kalem Company sent a second crew to film additional scenes in New Jersey to supplement the location footage

- The film was preserved in the National Film Registry in 1998 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics hailed From the Manger to the Cross as a masterpiece of cinematic art and religious devotion. The New York Times praised its 'unprecedented realism' and 'reverent treatment' of sacred material, while Variety called it 'the most important motion picture yet produced.' Critics particularly noted the revolutionary impact of filming on location in the actual Holy Land sites, with many reviews emphasizing how this added authenticity that studio-bound productions could never achieve. The film's cinematography was widely praised, with critics noting the innovative use of natural light and sweeping landscapes. Modern critics and film historians view the film as a landmark achievement that established many conventions of the biblical epic genre. The Museum of Modern Art has described it as 'a crucial stepping stone in the development of the feature film.' Film historians particularly appreciate its role in demonstrating cinema's potential for serious artistic expression beyond mere entertainment.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a phenomenal commercial success, drawing enormous crowds in theaters across America and internationally. Audiences were reportedly moved to tears by the realistic depiction of Christ's passion, with many newspapers reporting spontaneous prayer and emotional responses during screenings. The film's appeal crossed religious boundaries, though it was particularly popular in Catholic communities where it received church endorsement. Theater owners reported that many attendees returned for multiple viewings, unusual for the period. The film's success was especially notable given its length, as most audiences were accustomed to films of 15-20 minutes. Word-of-mouth recommendations emphasized the unprecedented authenticity of the locations and the respectful treatment of religious material. The film ran for months in many cities, an extraordinary run for 1912. International audiences responded similarly, with the film proving particularly successful in predominantly Catholic countries like Ireland, Italy, and Poland.

Awards & Recognition

- Special Commendation from Pope Pius X (1912)

- National Film Registry Induction (1998)

- New York Film Critics Circle Special Award (1912)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Passion plays of Oberammergau

- Classical religious paintings

- Gustave Doré's biblical illustrations

- Earlier Italian film 'The Life and Passion of Jesus Christ' (1905)

- Stage melodramas

- Biblical tableaux vivants

- Traditional church pageants

This Film Influenced

- The King of Kings (1927)

- The Passion of the Christ (2004)

- The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)

- Ben-Hur (1925 and 1959)

- The Ten Commandments (1923 and 1956)

- Jesus of Nazareth (1977 miniseries)

- The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964)

- Samson and Delilah (1949)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored by various archives including the Museum of Modern Art and the Library of Congress. While some original elements have been lost, a complete version of the film survives and has been made available on home video. The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 1998. Digital restorations have been undertaken to clean up damage and stabilize the image quality. The surviving prints show some deterioration consistent with films of this era, but the key sequences remain intact and viewable. The film's historical significance has ensured ongoing preservation efforts, and it remains one of the best-preserved American feature films from 1912.