Gentlemen of Nerve

"A Thrilling Comedy of Racing and Romance"

Plot

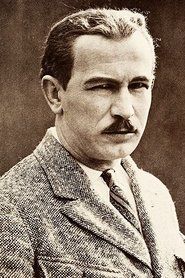

Mabel Normand and her beau attend an exciting auto race, where they encounter Charlie Chaplin and his friend Chester Conklin. The four spectators find themselves in increasingly chaotic situations as they try to gain better views of the race. When Chester attempts to sneak through a hole in the fence to get closer to the action, he becomes comically stuck, drawing the attention of a Keystone Kop. The ensuing pandemonium involves Charlie trying to free his friend while avoiding the police, creating a classic Keystone-style chase sequence filled with physical comedy and slapstick mishaps that culminate in the disruption of the auto race itself.

About the Production

This film was produced during Charlie Chaplin's first year at Keystone Studios, where he was still developing his iconic Tramp character. The auto race scenes were filmed on location at actual racing venues in the Los Angeles area, adding authenticity to the backdrop of the comedy. The film showcases Chaplin's early experimentation with physical comedy and his growing confidence in directing his own material.

Historical Background

1914 was a landmark year in cinema history, occurring during the transition from short films to feature-length productions and the establishment of Hollywood as the center of American filmmaking. The auto racing craze was sweeping America, with races drawing massive crowds and media attention, making it a perfect backdrop for popular entertainment. World War I had just begun in Europe, though the United States remained neutral, creating a climate where escapist entertainment was increasingly valued. The film industry was rapidly consolidating, with studios like Keystone pioneering the factory-like production system that would dominate Hollywood for decades. This period also saw the rise of movie stars as cultural icons, with Charlie Chaplin quickly becoming one of the most recognizable figures in the world.

Why This Film Matters

'Gentlemen of Nerve' represents an important milestone in the development of American comedy cinema and Charlie Chaplin's artistic evolution. The film demonstrates the emerging language of cinematic comedy, particularly the use of physical space and situational humor that would become hallmarks of silent comedy. It captures the zeitgeist of the early automobile age, reflecting society's fascination with speed and modern technology. The film also illustrates the collaborative nature of early Hollywood, with talents like Chaplin, Normand, and Conklin helping to establish the comedic conventions that would influence generations of filmmakers. As part of the Keystone Studios output, it contributed to the establishment of American slapstick comedy as a globally recognized art form.

Making Of

The production of 'Gentlemen of Nerve' took place during a pivotal moment in Charlie Chaplin's career, as he was beginning to assert creative control over his films at Keystone Studios. Chaplin and Mabel Normand had a complex working relationship, with both being ambitious filmmakers at the studio. The auto race sequences presented significant technical challenges for the 1914 production team, requiring them to coordinate filming with actual racing events. The famous scene where Chester Conklin gets stuck in the fence required multiple takes to perfect the timing and physical comedy elements. Chaplin was known for his meticulous attention to detail even in these early days, often rehearsing gags extensively before filming. The Keystone Studios lot provided the backdrop for many of the film's interior and fence scenes, while the racing sequences were filmed on location to capture the authentic excitement of early 20th-century auto racing.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Gentlemen of Nerve' reflects the standard practices of Keystone Studios in 1914, featuring static camera positions typical of the era but with innovative use of multiple angles to capture both the racing action and the comedy. The film employs medium shots for the character-driven comedy scenes and wider shots to establish the race setting and capture the scale of the auto racing events. The camera work during the racing sequences was particularly ambitious for its time, attempting to convey the speed and excitement of the races through careful framing and timing. The cinematography effectively balances the spectacle of the racing with the intimate comedy of the character interactions.

Innovations

While not technologically groundbreaking, 'Gentlemen of Nerve' demonstrated solid technical execution for its time, particularly in its integration of location footage with studio-shot material. The film's successful combination of actual auto racing footage with staged comedy sequences required careful planning and coordination, representing an early example of documentary-style elements being incorporated into fictional narrative. The production team's ability to capture clear images of fast-moving race cars with the camera equipment of 1914 was noteworthy, as was their effective use of depth in the fence-stuck sequence to enhance the physical comedy.

Music

As a silent film, 'Gentlemen of Nerve' was originally accompanied by live musical performance in theaters, typically featuring piano or organ accompaniment. The score would have been selected from standard Keystone Studios music libraries, with lively, upbeat pieces chosen to match the film's comedic tone and the excitement of the racing sequences. Modern restorations of the film have featured newly composed scores by silent film accompanists, often incorporating period-appropriate popular songs and classical pieces that would have been familiar to 1914 audiences. The music typically emphasizes the slapstick elements with jaunty rhythms and provides dramatic underscoring for the racing sequences.

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic sequence where Chester Conklin becomes stuck while attempting to crawl through a hole in the race track fence, creating a perfect visual gag as his legs flail helplessly while Charlie Chaplin frantically tries to free him before the approaching policeman discovers their attempted trespassing

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films Charlie Chaplin directed at Keystone Studios, marking his transition from actor to filmmaker

- The auto race featured in the film was an actual race that Keystone Studios filmed and incorporated into the comedy

- Mabel Normand was not only the female lead but also a prominent director and screenwriter at Keystone during this period

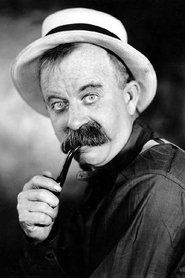

- Chester Conklin, who plays Charlie's friend, would become a regular Chaplin collaborator in the Keystone years

- The film showcases early examples of what would become Chaplin's signature style of combining pathos with physical comedy

- The 'Gentlemen of Nerve' title refers to the daring race car drivers of the era, though the film focuses more on the spectators

- This short was released during the height of the auto racing craze in America, making it particularly relevant to contemporary audiences

- The policeman character is played by Keystone regular Charles Avery, one of the original Keystone Kops

- The film was shot in just a few days, typical of the rapid production schedule at Keystone Studios

- Chaplin's Tramp character is still evolving in this film, not yet fully developed into the iconic figure he would become

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'Gentlemen of Nerve' were generally positive, with trade publications praising the film's energetic comedy and effective use of the auto race setting. The Motion Picture World noted the film's 'laugh-provoking situations' and Chaplin's growing confidence as a performer. Modern critics view the film as an important stepping stone in Chaplin's development, showing his progression from mere performer to filmmaker with a distinct comedic vision. Film historians appreciate the short for its documentation of early 20th-century auto racing culture and its role in establishing the conventions of American slapstick comedy.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by contemporary audiences, who were drawn to both the excitement of auto racing and the growing popularity of Charlie Chaplin's comedic persona. Moviegoers of the era particularly enjoyed the film's blend of action and comedy, with the racing sequences providing spectacle while the character-driven comedy delivered laughs. The short's success contributed to Chaplin's rapidly rising stardom and helped establish him as a bankable leading man. Modern audiences, when viewing the film through retrospectives and archives, appreciate it as a fascinating glimpse into early cinema and the formative years of one of cinema's greatest artists.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mack Sennett's Keystone comedy style

- French and Italian slapstick traditions

- Vaudeville comedy routines

- Early American film comedy

This Film Influenced

- The Champion (1915)

- The Tramp (1915)

- The Bank (1915)

- A Night Out (1915)

- Later Chaplin Keystone comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form and has been preserved by various film archives, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Library of Congress. Multiple 35mm and 16mm copies exist, and the film has been digitally restored for home video releases and streaming platforms. The preservation quality is generally good, though some deterioration typical of films from this era is visible in existing prints.