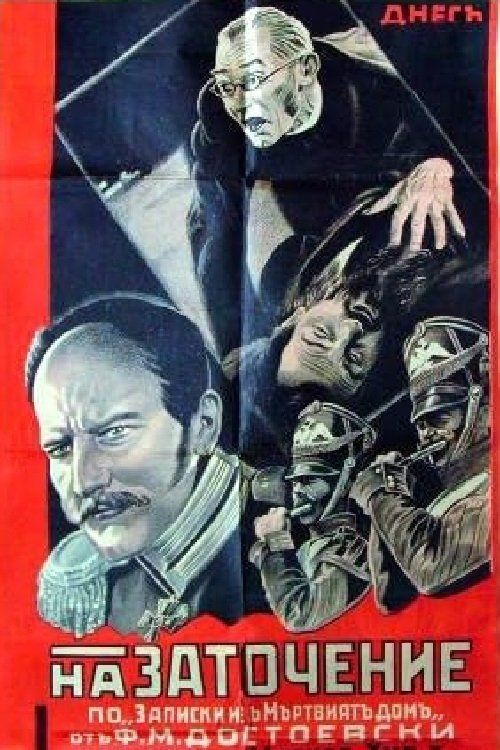

House of the Dead

Plot

Based on Fyodor Dostoevsky's autobiographical novel, this Soviet drama depicts the author's harrowing experiences in a Siberian prison camp following his arrest for involvement with the Petrashevsky Circle. The film follows Alexander Goryanchikov, a nobleman sentenced to four years of hard labor, as he confronts the brutal realities of prison life and encounters fellow inmates from various social classes. Through his interactions with prisoners and guards, he witnesses the dehumanizing effects of the penal system while discovering unexpected moments of humanity and redemption. The narrative explores themes of suffering, spiritual transformation, and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of institutional oppression. As Goryanchikov adapts to his new reality, he gains profound insights into human nature and the social conditions that lead to crime and punishment.

About the Production

This adaptation was produced during the early Soviet period when literary adaptations were encouraged to make classic Russian literature accessible to the masses. The film was part of a broader cultural initiative to reinterpret pre-revolutionary literature through a socialist lens. The production faced the challenge of adapting Dostoevsky's complex psychological novel within the constraints of early Soviet cinema technology and ideological requirements.

Historical Background

The film was produced during Stalin's First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932), a period of rapid industrialization and cultural transformation in the Soviet Union. This era saw the consolidation of socialist realism as the dominant artistic style, though this 1932 adaptation still retained elements of the experimental approaches of the 1920s. The early 1930s marked a significant transition in Soviet cinema with the introduction of sound technology and increasing state control over artistic production. Dostoevsky's works, once considered ideologically problematic, were being reinterpreted through a Marxist lens that emphasized social criticism over religious and psychological themes. The film's release coincided with the height of the Great Turn, when Soviet culture was being systematically reshaped to serve revolutionary goals.

Why This Film Matters

This adaptation represents an important moment in the Soviet engagement with Russia's literary heritage, demonstrating how classic pre-revolutionary works were reinterpreted for socialist audiences. The film contributed to the broader Soviet project of claiming Russia's cultural legacy while reframing it through revolutionary ideology. As an early sound film, it showcases the technical and artistic developments in Soviet cinema during the transitional period of the early 1930s. The adaptation also reflects the complex relationship between Soviet culture and the psychological depth of Dostoevsky's writing, attempting to reconcile individual consciousness with collective social consciousness. The film serves as a historical document of how Soviet cinema approached the challenge of adapting complex literary works while meeting ideological requirements.

Making Of

The production took place during a transitional period in Soviet cinema when the industry was moving from silent films to sound technology. Director Vasili Fyodorov, working within the constraints of early Soviet film production, had to balance artistic interpretation with ideological requirements. The casting of Nikolai Khmelyov, a renowned stage actor from the Moscow Art Theatre, brought theatrical gravitas to the adaptation. The production team faced challenges in recreating the 19th-century Siberian prison environment with limited resources, relying heavily on studio sets and minimal location shooting. The film's approach to Dostoevsky's complex psychological themes reflected the Soviet emphasis on social and collective rather than individual perspectives.

Visual Style

The visual style likely reflected the transitional nature of early 1930s Soviet cinema, combining elements of the experimental approaches of the 1920s with the emerging conventions of sound film production. The cinematography would have emphasized the stark contrast between the prisoners' harsh conditions and moments of human dignity, using lighting and composition to reinforce the social themes. The prison sets would have been designed to convey the oppressive atmosphere of the Tsarist penal system while allowing for the psychological depth of the characters to emerge through visual means.

Innovations

As one of the early Soviet sound films, this adaptation represented a technical milestone in the Soviet film industry's transition from silent to sound production. The film would have utilized the early sound recording equipment available in Soviet studios during the early 1930s, presenting challenges in capturing clear dialogue while maintaining dramatic impact. The production team had to solve technical problems related to sound recording in studio sets designed to replicate 19th-century prison conditions.

Music

As an early Soviet sound film, the soundtrack would have utilized the new technology to enhance the dramatic impact of key scenes while maintaining the emphasis on dialogue and narrative clarity typical of early sound cinema. The musical score likely incorporated elements of Russian folk music and classical themes to evoke the 19th-century setting while remaining accessible to contemporary Soviet audiences. Sound effects would have been used to create the oppressive atmosphere of the prison environment, from the clanking of chains to the harsh commands of guards.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the earliest Soviet film adaptations of Dostoevsky's work, made during a period when the author's works were being re-evaluated through a Marxist lens

- The film was produced during the First Five-Year Plan, a time of rapid industrialization and cultural transformation in the Soviet Union

- Dostoevsky's original novel was based on his own experiences in a Siberian prison camp from 1850-1854

- The film adaptation had to navigate the complex relationship between pre-revolutionary Russian literature and Soviet ideology

- 1932 was a significant year in Soviet cinema, marking the transition from silent films to sound production

- The cast featured prominent actors from the Moscow Art Theatre, known for their psychological realism

- The film was part of a series of literary adaptations produced by Soviet studios in the early 1930s

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics likely evaluated the film based on its faithfulness to socialist principles and its success in making classic literature accessible to working-class audiences. The psychological complexity of Dostoevsky's original work may have presented challenges for critics operating within the framework of socialist realism. Modern film historians view this adaptation as an important example of early Soviet literary cinema, though it remains relatively obscure compared to other Soviet classics of the period. The film is often discussed in the context of how Soviet cinema handled the adaptation of pre-revolutionary literary masterpieces during the early Stalinist period.

What Audiences Thought

The film likely appealed to Soviet audiences interested in literary adaptations and the exploration of social justice themes inherent in Dostoevsky's prison narrative. Working-class viewers would have appreciated the film's focus on the brutal conditions of the penal system, which could be interpreted as criticism of Tsarist oppression. The adaptation's emphasis on social rather than religious aspects of Dostoevsky's work would have resonated with Soviet audiences' secular worldview. The film's release during the cultural transformation of the early 1930s meant it reached audiences hungry for both entertainment and ideological education.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Dostoevsky's Notes from the House of the Dead

- Soviet socialist realism

- Moscow Art Theatre acting tradition

- Early Soviet cinema techniques

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet adaptations of Dostoevsky

- Soviet prison films

- Literary adaptations in Soviet cinema