Hypocrites

Plot

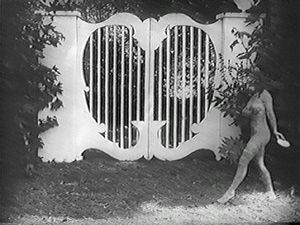

The film tells two parallel stories: one set in medieval times following a monk named Gabriel who creates a nude statue representing Truth, which is condemned by the church and leads to his death by an ignorant mob. The second story is contemporary, showing a modern minister who preaches against sin while secretly indulging in worldly pleasures. Throughout both narratives, a ghostly nude figure representing Truth appears, visible only to those who are pure of heart, while hypocrites cannot see her. The film culminates in a powerful message about religious hypocrisy and the importance of seeing truth beyond superficial appearances.

About the Production

The film was groundbreaking for its use of full-frontal nudity in a non-exploitative context. Lois Weber used double exposure techniques to make the nude Truth figure appear ethereal and ghostly. The production faced significant censorship challenges in many states, with some requiring cuts or outright banning the film. Weber fought these censorship battles personally, arguing for artistic integrity and the film's moral message.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the Progressive Era in America, a time of social reform and moral crusading. The early 1910s saw the rise of censorship boards across the country, particularly following the 1915 Supreme Court decision in Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, which declared films were not protected by free speech rights. Women were gaining increasing visibility in society with the suffrage movement in full swing, though female directors remained rare. The film industry was transitioning from short films to feature-length productions, and Hollywood was establishing itself as the center of American filmmaking. World War I was raging in Europe, affecting international film distribution, while America remained neutral until 1917.

Why This Film Matters

'Hypocrites' stands as a landmark in early cinema for multiple reasons. It represents one of the earliest examples of a female director using film as a medium for social commentary and moral instruction. The film's bold use of nudity challenged prevailing censorship standards and pushed the boundaries of acceptable content in cinema. It demonstrated that silent film could tackle complex philosophical themes about truth, morality, and human nature. The film's success helped establish Lois Weber as one of the most important directors of the silent era, male or female. Its themes of religious hypocrisy remain relevant today, and the film is studied in film schools as an example of early feminist filmmaking and artistic courage in the face of censorship.

Making Of

Lois Weber approached 'Hypocrites' as both an artistic statement and a moral crusade. She cast her husband Harry A. Gant in a supporting role and worked closely with cinematographer Philip R. Du Bois to achieve the film's visual effects. The nude scenes were carefully choreographed and shot to emphasize artistic rather than sexual elements. Weber faced immense pressure from studio executives and censorship boards but refused to compromise her vision. The film's production was marked by Weber's meticulous attention to detail and her willingness to tackle controversial subjects head-on. She reportedly screened the film for religious leaders to gain their support, successfully convincing many of its moral value.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Philip R. Du Bois was innovative for its time, featuring extensive use of double exposure to create the ethereal effect of the nude Truth figure. The film employed soft focus techniques to differentiate between the realistic contemporary sequences and the dreamlike medieval sequences. Du Bois used lighting creatively, with the Truth figure often appearing in a halo of light that made her seem otherworldly. The medieval sequences were shot with a more pictorialist style, while the modern scenes used more straightforward cinematography. The film also featured some of the earliest examples of symbolic lighting in American cinema.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in early cinema. Most notably, it used sophisticated double exposure techniques to make the nude Truth figure appear transparent and ghostly, a complex technical feat for 1915. The film also featured elaborate cross-cutting between the medieval and modern storylines, helping establish parallel editing as a narrative device. Weber used lighting creatively to create mood and symbolism, particularly in the scenes featuring the Truth figure. The film's production design was ambitious for its time, with detailed sets for both the medieval and modern sequences.

Music

As a silent film, 'Hypocrites' was accompanied by live musical performances during its original theatrical run. Theaters typically provided orchestral or organ accompaniment, with some using compiled classical pieces while others commissioned original scores. The musical selections were meant to enhance the film's moral and emotional themes, often including religious and classical pieces. No original score was composed specifically for the film, as was common practice in 1915. Modern restorations have been shown with newly commissioned scores by silent film composers.

Famous Quotes

"The naked truth is always beautiful" - Intertitle card

"Hypocrisy is the homage vice pays to virtue" - Intertitle card

None are so blind as those who will not see" - Intertitle card

"Truth is eternal, though men may die" - Intertitle card

Memorable Scenes

- The appearance of the nude Truth figure floating through the medieval monastery, visible only to the pure-hearted monk Gabriel

- The climactic scene where the mob destroys the statue while Truth watches impassively

- The parallel scene in the modern story where the minister cannot see Truth while his congregation can

- The opening sequence establishing the dual narrative structure

- The final scene where Truth stands triumphant over the ruins of hypocrisy

Did You Know?

- Lois Weber was one of the few female directors in early Hollywood and the first woman to direct a feature-length film in America

- The nude actress (Margaret Edwards) was only 16 years old when she portrayed 'The Naked Truth'

- The film was banned in several cities and states including Ohio and Pennsylvania for its nudity

- Weber wrote, directed, produced, and edited the film herself, demonstrating remarkable control over her work

- The film's title was originally going to be 'The Naked Truth' but was changed to 'Hypocrites'

- Weber used a special camera technique involving multiple exposures to create the ghostly effect of the Truth figure

- The film was praised by progressive reformers and women's groups for its moral message

- Weber reportedly paid the nude actress an extra $50 bonus for her controversial role

- The film was one of the first to use nudity as an artistic rather than sensational device

- Weber defended the film before censorship boards, arguing that 'the nude figure is not immoral but beautiful'

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were divided but largely appreciative of the film's artistic merits and moral message. The New York Dramatic Mirror praised it as 'a masterpiece of screen art' while Variety noted its 'unusual daring and originality.' Many reviewers specifically commended Weber's direction and the film's technical achievements. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a pioneering work of feminist cinema. The Village Voice later called it 'one of the most audacious films ever made in Hollywood.' Film historians consider it a crucial work in understanding both Weber's career and the evolution of American cinema's treatment of controversial subjects.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reaction was mixed and often polarized. Progressive and educated viewers generally praised the film's artistic qualities and moral message. However, more conservative audiences were shocked by the nudity, leading to protests and boycotts in some cities. The controversy actually increased public interest, making the film a commercial success despite censorship battles. Many viewers reported being moved by the film's message about religious hypocrisy. The film's notoriety made it one of the most discussed movies of 1915, with newspaper columns and letters to the editor debating its merits and appropriateness for months after its release.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Classical Greek sculpture

- Medieval religious art

- Progressive Era social reform movements

- Symbolist art movement

- Victorian moral literature

- Biblical stories of prophets

- Platonic philosophy of forms

This Film Influenced

- Intolerance (1916) by D.W. Griffith

- The Scarlet Letter (1926)

- The Ten Commandments (1923)

- The Miracle Woman (1931) by Frank Capra

- The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) by Pier Paolo Pasolini

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress and has been restored by several film archives. A complete 35mm print exists and has been digitally restored. The film is part of the National Film Registry, having been selected for preservation in 1996 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. The restoration has been screened at film festivals and museums worldwide.